CHAPTER 9 THE BANKING SECTOR

BANKING DEVELOPMENTS

Banking institutions play a dominant role in Macau's simplistic financial sector. At the end of 1998, there were 22 commercial banks in Macau, one of which was an offshore banking unit.1 Macau does not host any investment banks and fund management houses in line with its backward development of financial markets. The Territory has an inactive money (interbank) market,and no capital markets.

The history of modern banking in Macau is rather recent. Before the 1970s, there was only one authorized commercial bank in Macau - the Portuguese-controlled Banco Nacional Ultramarino (BNU), which was also the noteissuing bank and the banker to the Government. A number of native Chinese banking institutions, or An Ho, co-existed with the BNU. An Ho were tightly held family businesses managed by traditional methods. Most of them started their business as bullion dealers, moneychangers and remittance houses. They later participated in the loan and deposit businesses in the absence of a regulatory system. Some An Ho also issued pangtans, which circulated as a medium of exchange.2 The number of An Ho and moneychangers once rose to over 300 during WWII, due to the inflow of capital from Mainland China and Hong Kong. After WWII, the number of An Ho dropped to below 20.

Gold trading was an important business for large An Ho in the early postwar period. The prohibition of gold trading in Hong Kong significantly promoted this business in Macau. The Macau Government initially granted the exclusive right to Ng Fuk Tong, which was allied with some An Ho, and the gambling monopoly, Tai Hing Company.3 As gold trading provided large profit margins, it helped the involved An Ho to build up strong capital base.The accumulated capital later facilitated their transformation into modern commercial banks.4

In 1970, Portugal promulgated the first Banking Ordinance (Decree Law No. 411/70), which was applicable to Macau. The law granted banking supervisory authority to the governor, with the assistance from the noteissuing bank. It fixed the minimum capital requirement for commercial banks at MOP5 million, An Ho at MOP2.5 million and moneychangers at MOP20,000.Many An Ho failed to meet the capital requirement and as a result, their business scope, in particular, that in relation to deposit taking, was limitedby the regulator. Only a few well-capitalized An Ho successfully developed into commercial banks. They included Tai Fung, Weng Hang, Seng Heng,Luso International (formerly Key Che An Ho) and Delta Asia (formerly Hang Seng An Ho).

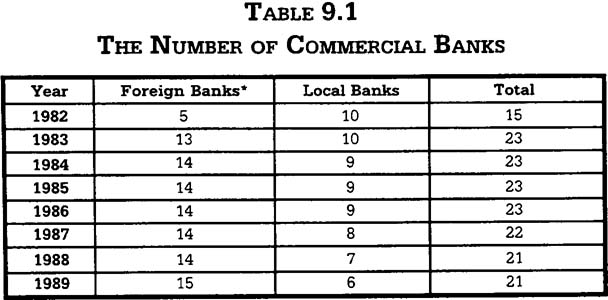

Meanwhile, the close Hong Kong-Macau relationship and inflows of manufacturing investment from Hong Kong pushed some Hong Kong-based banks, such as Hongkong and Shanghai Banking Corporation, Overseas Trust Bank and the Bank of Canton, to open their branch offices in Macau.5 The China-controlled Nam Tong Bank was established in 1974.6 In the early 1980s,the number of commercial banks in Macau increased to 15, of which local banks formed the dominant group.

As the Macau economy experienced an industrial take-off,7 the banking sector started to lag behind the economic development. In 1980, the Instituto Emisor de Macau (IEM) was established. Two years later, the Government promulgated the Modern Banking Ordinance (Decree Law No. 35/82/M), under which the primitive Banking Supervision Division was repealed.8 The Division's duties were taken over by the IEM. The Ordinance formulates the core of banking regulations in Macau, though there have been some amendments to the Ordinance in later periods in line with the change in operating environments. Specifically, it set out the provision requirement of reserves against risks; the legal authority of the supervisory body to receive regularly operating information from banks and to deal with banking crises; and regulation of credits such as those relating to connected lending. The capital requirement of commercial banks was also raised to MOP30 million.9

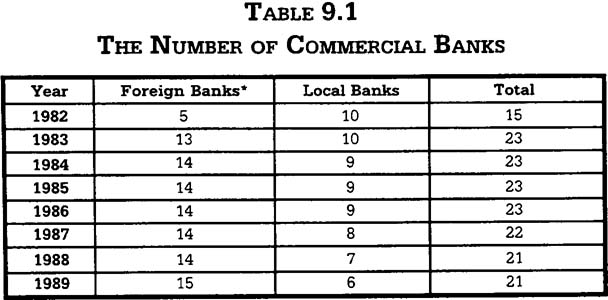

The enactment of the modern banking ordinance immediately stimulated a massive inflow of foreign banks. The number of foreign banks jumped from five in 1982 to 13 in 1983 (Table 9.1). For the first time, the number of foreign banks exceeded the number of local banks.

Note: *With head office outside Macau.

Sources: Instituto Emisor de Macau Report and Accounts, various issues;Autoridade Monetaria e Cambial de Macau Annual Report, various issues.

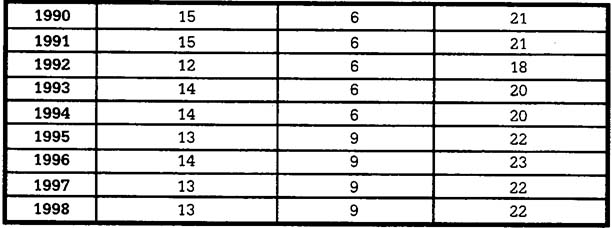

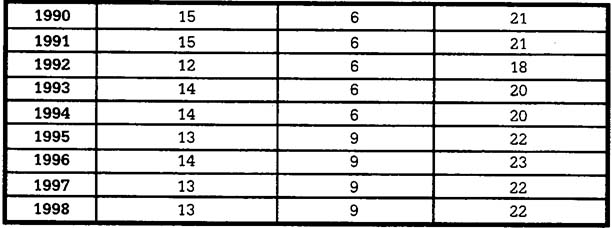

The foreign participation fostered a rapid growth of banking activities.In the four-year period 1986-1989, the asset size of the banking sector was more than doubled, from MOP27.8 billion to MOP58.8 billion (Table 9.2). The average annual growth was higher than 20 percent. Offshore banking particularly benefited from the active participation of foreign banks.10 It should be noted that the rapid expansion also brought increased risk, which, to some extent, undermined banking stability. In the 1980s, Macau experienced one bank failure and four notable bank runs.11

Sources: Instituto Emisor de Macau Report and Accounts,various issues;

Autoridade Monetaria e Cambial de Macau Annual Report,various issues.

Since the 1990s, the banking expansion has moderated. Growth of domestic credits has been curbed by the local recession, but offshore banking business has still remained vigorous. Bank assets now amount to about three times of GDP, indicating a mature stage of banking development in the Macau economy by world standards. Twenty two banks currently operate about 140 branch offices and employ 4,000 workers in the Territory.

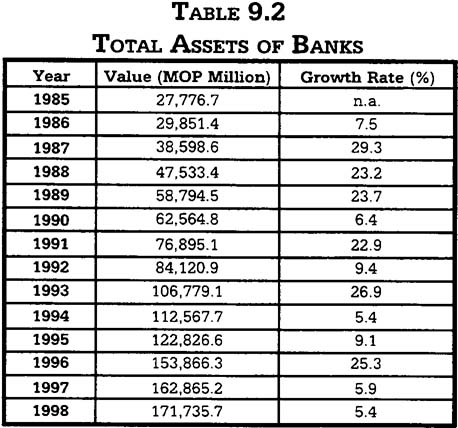

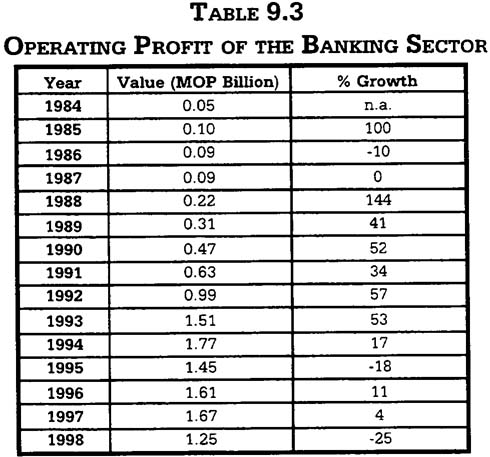

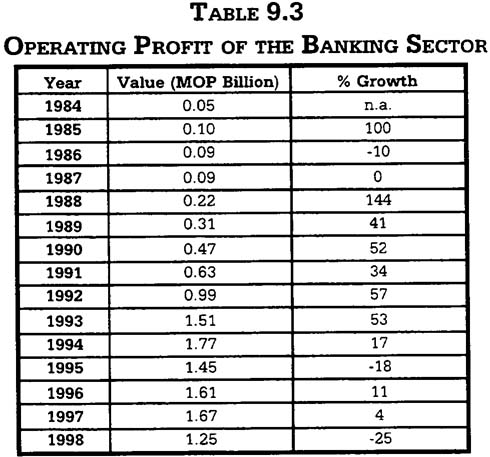

Banking is basically a very profitable business in Macau, though its operating profit has fallen in recent years largely due to a drastic increase in loan provision (Table 9.3).12 Local banks continue to rely on traditional loan and deposit businesses. In 1998, interest incomes accounted for 74.2 percent of the banks' total incomes,13 notwithstanding that significant efforts have been made by all banks on diversifying their banking services into the areas of investment product sales, credit cards and phone banking.

Sources: Instituto Emisor de Macau Report and Accounts.various issues;

Autoridade Monetaria e Cambial de Macau Annual Report.various issues.

ONSHORE OR DOMESTIC BANKING

As mentioned in the previous section, Macau's banks continue to count on traditional deposit and loan business. Deposits remain the largest item of bank liabilities, while bank credits are the largest item of bank assets.

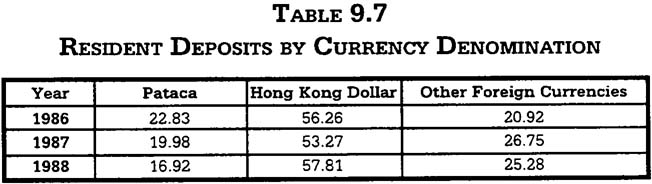

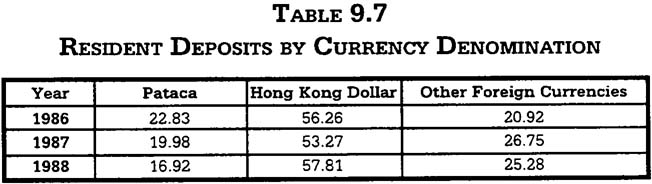

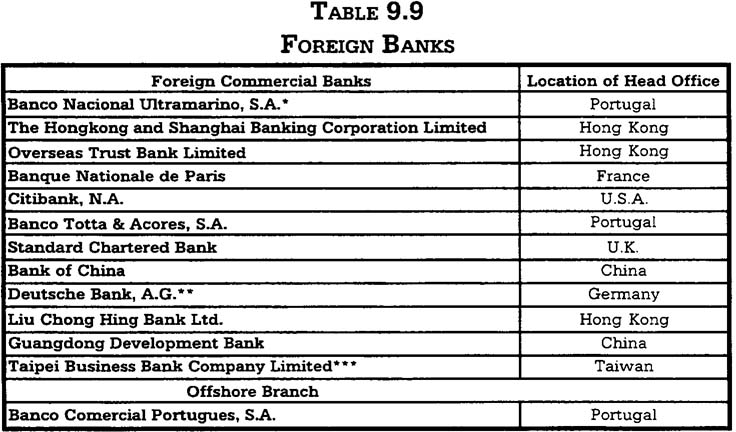

In 1984, resident deposits in the local banking system valued at MOP8.1billion. It increased to MOP84.6 billion in 1998 - an impressive growth of 944 percent, as compared with a nominal GDP growth of only 362 percent during the period. Resident deposits in Macau include demand deposits, savings deposits, notice deposits and time deposits. The share of time deposits has been increasing over time, and reached 77.1 percent in 1998. Over 80 percent of time deposits were of short term with maturity equal to or less than three months. By currency denomination, Hong Kong dollar deposits accounted for over half of resident deposits.

The Government does not regularly release data of market shares, but constant observations reveal that the deposit structure is highly concentrated.Two China-controlled banks - the Bank of China (BOC) and the Tai Fung Bank are said to have a share of over half of the residents' deposits. The Seng Heng Bank and the BNU are estimated to each acquire about a 10 percent share.

In 1984, domestic credits amounted to MOP6.2 billion. It increased to MOP61.2 billion in 1998 - a large gain of 887 percent in 14 years. Domestic credits include customer loans, financial investments and claims on monetary institutions (monetary bills and interbank loans) in Macau's banking system.Seventy-nine percent of domestic credits were extended to the non-bank private sector in 1998. Nineteen percent of domestic credits were AMCM-issued monetary bills purchased by banks. The others were mainly interbank lending. Unlike other developed banking systems, Macau has an inactive interbank market and negligible bank credits to the public sector. Monetary bills are short-term, pataca-denominated, public debt paper, issued by the AMCM for liquidity adjustment purpose, rather than financing purpose.14

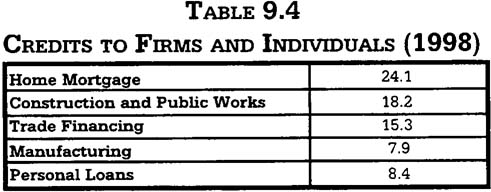

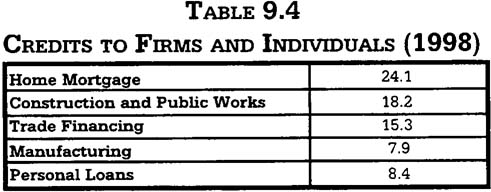

While deposits are mostly short-term, about half of the loans to domestic firms and individuals have a maturity of longer than two years. The domestic credit structure as shown in Table 9.4 reveals two notable characteristics of the domestic economy. First, the largest business sector in Macau the tourism and gambling sector - is extremely cash-rich and has a low investment requirement. As a result it never relies on bank loans, but some local banks rely on it as a major source of funds. Second, domestic credits are concentrated on property-related sectors.

The first character restricts the growth potential of domestic banking business. The second character echoes the limited scope of domestic credit market - banks are unwilling to extend credits to domestic SMEs, which are overwhelmingly dominant in number. Thousands of small enterprises in Macau find it very difficult to secure longer term bank loans. On the other hand,banks tend to extend credits to better-capitalized construction firms, property developers and public projects. Home mortgage is also believed to be of low risk as it has 100 percent collateral.15 To cater to the banks' requirements,SMEs usually obtain secured loans from banks with real estates as collateral.

Note: Credits include loans and advances, discounted bills and other commercial papers.

Unit: % share of the total

Sources: Instituto Emisor de Macau Report and Accounts, various issues;

Autoridade Monetaria e Cambial de Macau Annual Report, various issues.

Credit business is also reported to concentrate in a small number of banks including BOC, Tai Fung, Seng Heng and Weng Hang.

OFFSHORE BANKING

Offshore banking has been a major banking business in Macau for two decades. It basically involves raising funds by non-residents for lending purposes to other non-residents.

Compared with other offshore banking centres, Macau has a rather brief history of offshore banking development. The authorities enacted the Modern Banking Ordinance (Decree Law No. 35/82/M) in 1982, under which for the first time offshore banks were officially defined as one type of monetary institutions.16 The Government did not specify their licensing requirements, business scope and regulatory regime until the proclamation of the Offshore Banking Ordinance (Decree Law No. 25/87/M) in 1987.17 The offshore activity, however, has developed into a major banking business in Macau right before the legislation. According to the IEM, the offshore activity accounted for 40 percent of the turnover of the local banking sector in the late 1980s.18 In 1992, the authoritative New Palgrave Dictionary of Money and Finance classified Macau as "one of the 53 geographically scattered countries in the world engaging in offshore banking".

The Offshore Banking Ordinance enacted in 1987 has provided for the granting of offshore banking licences with tax exemptions and the waiving of some domestic regulations. It aims to encourage reputable foreign credit institutions to establish their offshore banking operations in Macau. The legislation, however, is far from successful in attracting foreign participation in Macau's banking sector. Currently, only one offshore banking unit operates in Macau.The offshore branch of Portugal's Banco Comercial Portugues, S.A. was authorized in 1993, six years after the proclamation of the Offshore Banking Act.

The poor response to the legislation does not mean that offshore banking business is insignificant in Macau's banking sector. The growing offshore business in fact continues to be partly operated by commercial banks in the Territory, which have a full banking licence. One special feature of Macau's offshore banking business is that local banks are also actively engaged in offshore activities. The active participation of commercial banks, both foreign and local, in offshore business reflects the unsuccessful insulation of offshore activities from domestic business in Macau's free and open economic system.The low tax system in Macau also provides little incentive for credit institutions to legally distinguish themselves as offshore banking units.

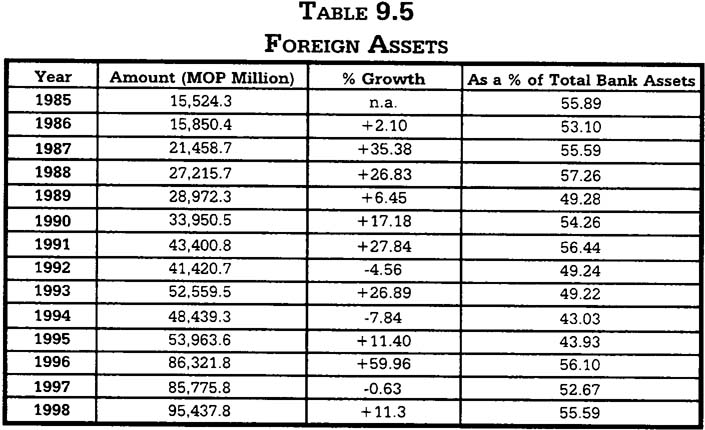

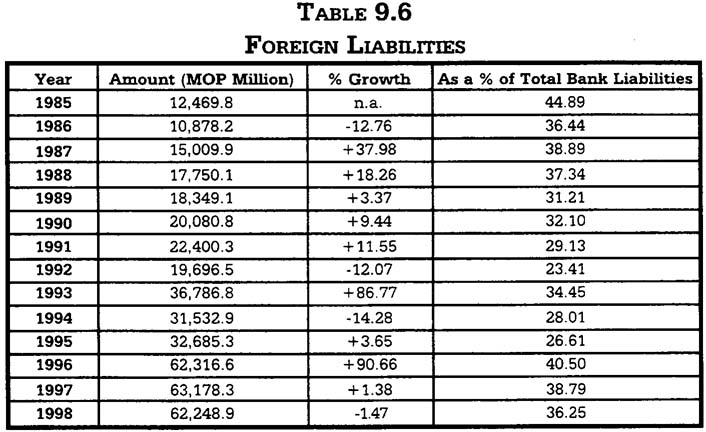

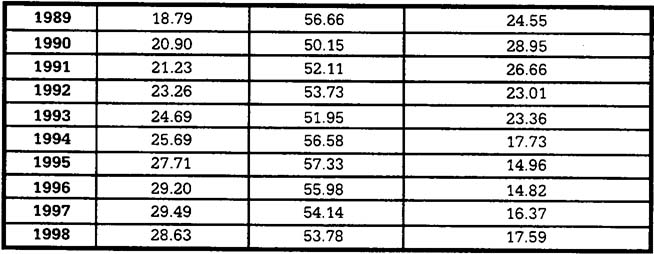

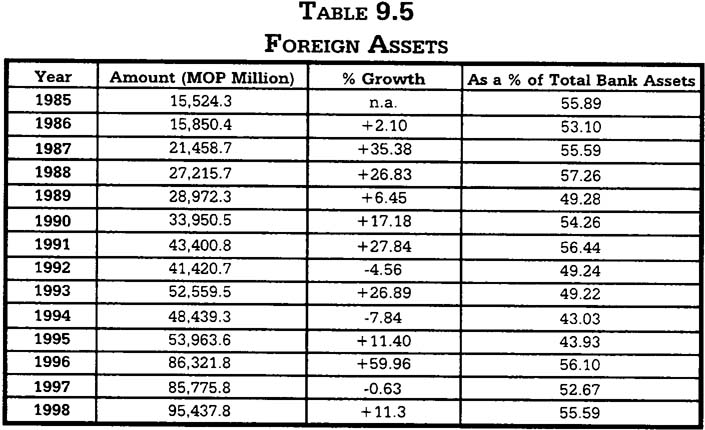

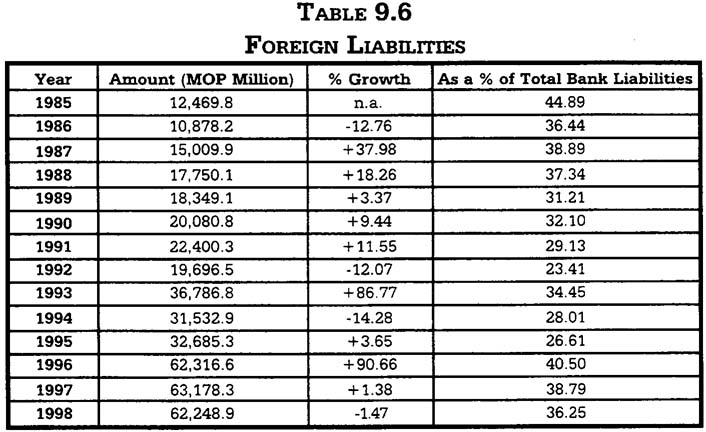

It is generally agreed that foreign assets and liabilities of the banking sector are major indicators of offshore or international banking business. At the end of 1998, foreign assets of the banking sector amounted to MOP95.4billion, which accounted for 55.6 percent of total bank assets (Table 9.5). The value of foreign liabilities was MOP62.2 billion or equivalent to 36.3 percent of the total bank liabilities (Table 9.6). The two figures indicate the significance of offshore banking activity and the external orientation of Macau's banking system. It is observed that the shares and growth rates of foreign assets and liabilities have demonstrated sharp fluctuations, probably due to the emphasis on short-term interbank transactions.

Sources: Instituto Emisor de Macau Report and Accounts, various issues;Autoridade Monetaria e Cambial de Macau Annual Report, various issues.

Sources: Instituto Emisor de Macau Report and Accounts, various issues;Autoridade Monetaria e Cambial de Macau Annual Report, various issues.

Foreign assets have been markedly larger than foreign liabilities, reflecting the virtual integration between the onshore and offshore banking sectors and the continued existence of excessive domestic funds. One reason for the onshore-offshore integration is that resident deposits - the major source of onshore funds - have a dominant foreign currency portion (Table 9.7). It implies a serious currency substitution phenomenon in the Territory.19 The ratio of foreign currency deposits to total deposits always stays at a high level of over 70 percent, though it has slightly declined in recent years. As a result,local commercial banks do not encounter the usual currency mismatch problem when engaged in offshore lending business. In 1998, 34.8 percent of foreign assets were financed by domestic funds. As foreign assets are larger than foreign liabilities, Macau's banking sector is a net creditor to the rest of the world.20

Unit: as a proportion of total deposits

Sources: Instituto Emisor de Macau Report and Accounts, various issues;Autoridade Monetaria e Cambial de Macau Annual Report, various issues.

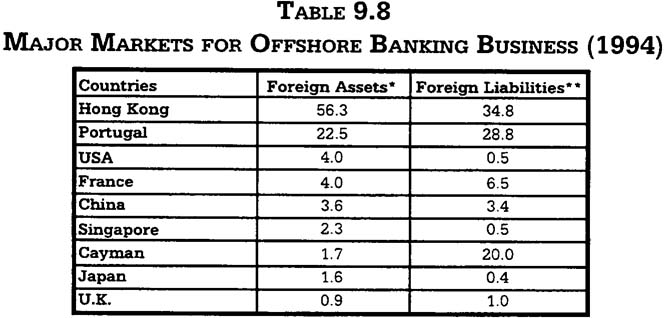

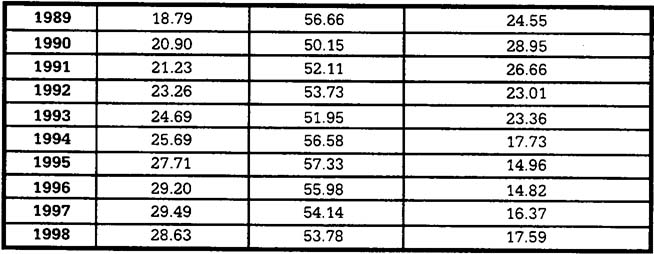

As the AMCM ceased to release the country breakdowns of foreign assets and liabilities after 1994, up-to-date analysis of the sources and uses of offshore funds is subject to certain limitations. Based on the strong presence of their banking institutions in the Territory and the official data for 1994, Hong Kong and Portugal are estimated to be the two most important markets for Macau in terms of sources and uses of offshore bank funds (Table 9.8). The US,China, France, the Cayman Islands and Japan are the other significant counterparties of Macau in offshore banking business. In 1994, Hong Kong was the largest outside debtor in net terms to Macau's banking sector, while the Cayman Islands was the largest outside creditor to the Territory's banking sector.

Notes:*Claims on banks abroad plus credits to non-bank customers.

**Liabilities towards banks abroad plus non-resident deposits.

Unit: as a percentage of the all-country total.

Source: Autoridade Monetaria e Cambial de Macau Annual Report, 1994.

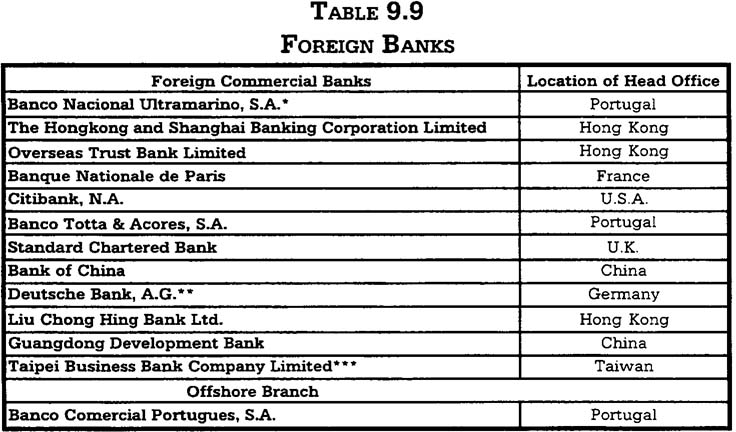

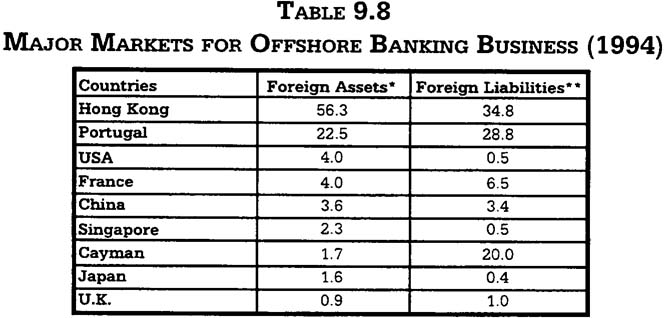

The large share of Hong Kong can be explained by Macau's continued reliance on the well-developed financial markets in Hong Kong, the dominant share of Hong Kong dollar deposits in the local banking sector and Macau's weak financial links with other countries. The unsatisfactory attempt to attract foreign banks to Macau has inhibited the Territory's establishment of direct financial links with foreign countries. As shown in Table 9.1, in 1997 the number of foreign banks in Macau was 13, which was about the same number in the early 1980s. The promulgation of the Modem Banking Ordinance in 1982 stimulated a massive inflow of foreign banks to the Territory in the following year, but the stimulus proved to be short-lived. Over the past fifteen years, the number of foreign banks has hardly seen any meaningful gain. Meanwhile, Macau's foreign banks come from a small number of countries, which also limit Macau's scope of financial links with the outside world (Table 9.9). The lack of internationally active banks based in Macau explains why the offshore banking business is concentrated on the simple form of interbank transactions.

Notes: *In July 1999, BNU established a locally incorporated subsidiary bank, Banco BNU Oriente,S.A.R.L., which will gradually take up BNU's Macau operations. Once the transformation has been completed, BNU will be classified as a "local" bank. See Portaria No. 284/99/M. **Announced to close in 1999. ***Renamed to International Bank of Taipei in 1998.

Source: Autoridade Monetaria e Cambial de Macau Annual Report. 1998.

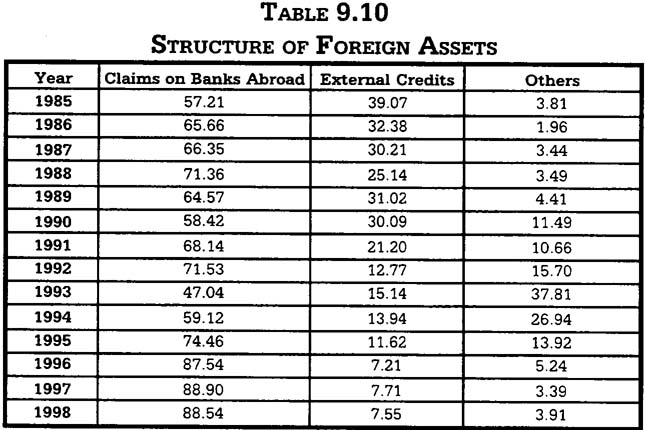

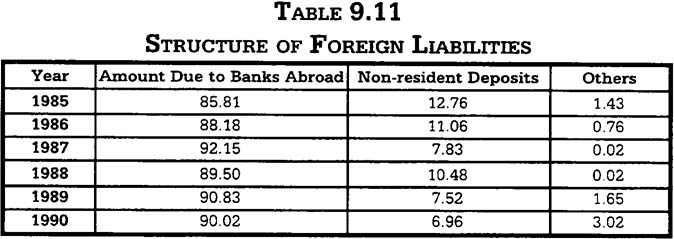

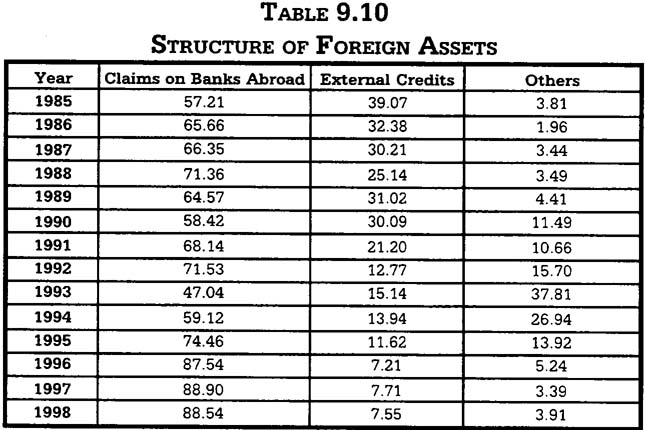

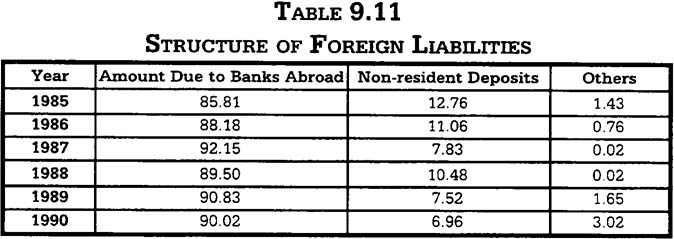

Tables 9.10 and 9.11 show that the majority of offshore transactions are of interbank nature. Close to 90 percent of foreign assets are claims on banks abroad, while over 80 percent of foreign liabilities are due to banks abroad.The buoyant offshore interbank activities explain the quiet interbank market in Macau as mentioned above. The small share of external credit to non-bank customers should be attributed to the lack of internationally active banks and hence of loan syndication activity in Macau. As the largest syndication centre in Asia, Hong Kong, on the other hand, hosts over 300 foreign financial institutions from more than 30 countries.21 It has arranged huge sums of syndicated loans to non-banks, particularly in the Asia-Pacific region.

Foreign assets excluding interbank placements and external credits mainly compose of financial investments abroad, which play a role in diversifying credit and exchange risks. On the liability side, non-resident deposits are the second largest item after interbank borrowing.

Unit: as a percentage of the total

Sources: Instituto Emisor de Macau Report and Accounts, various issues;Autoridade Monetaria e Cambial de Macau Annual Report, various issues.

Unit: as a percentage of the total

Sources: Instituto Emisor de Macau Report and Accounts, various issues;Autoridade Monetaria e Cambial de Macau Annual Report. various issues.

IMPACT ON THE DOMESTIC ECONOMY

Unlike onshore banking, which has an apparently inextricable link to domestic activities, offshore banking never exhibits a clear-cut contribution to the domestic economy. Previous empirical studies suggest that the net benefits of offshore banking business to the domestic economy are small (Johnson 1976, McCarthy 1979). Jao (1997) argues that it is because an offshore banking centre is deliberately created to insulate the domestic economy from the offshore sector. As mentioned above, there is no distinct boundary between onshore and offshore business that can be observed in Macau's integrated banking system. The implication of offshore banking operation for Macau's domestic economy should therefore require further verification.

The potential contributions of offshore banking business to the domestic economy include employment, national income, foreign exchange earnings from exports of banking services and tourist receipts,22 and government receipts (Gerakis and Roncesvalles 1983). Given the lack of data, it is not feasible to give satisfactory quantitative estimates for all these impacts on the real sector.

With respect to the national income, the Government groups banking production into a single category called Finance, Insurance and Real Estate in the estimation of the production-based GDP. In 1996, this production category accounted for 19.8 percent of Macau's GDP or contributed roughly MOP11.5billion to the GDP.23 The 19.8 percent share represents a gain of 4.8 percentage points from 15 percent in 1989 - the first year for which the productionbased GDP figures are available. However, as further breakdown of various production activities in the category is not available, it is not possible to single out the contribution of banking to the national income.

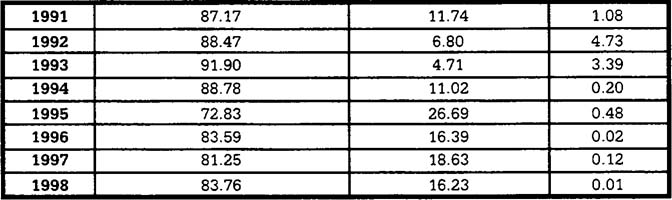

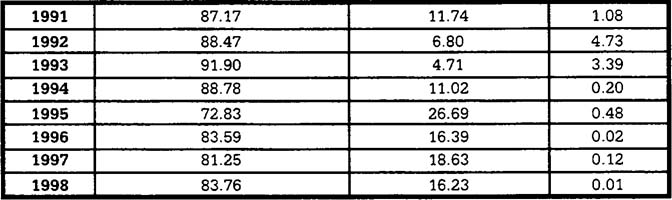

Similarly, the contribution of offshore banking to the balance of payments (BOP) cannot be quantified precisely. With respect to trade accounts, exportsof banking services are classified into an expenditure group called "non-industrial services", which amounted to MOP1.2 billion in 1998 or accounted for 5.4 percent of total exports of services. Individual impact of banking services cannot be evaluated given the unavailability of further breakdown. With respect to capital accounts, Macau's banking sector is normally exporting capital. As shown in Table 9.12, the net foreign assets of the banking sector have been largely increasing since the middle of the 1980s.24

Note: *+ increase, - decrease.

Source: Underlying data from various issues of Instituto Emisor de Macau Report and Accounts and Autoridade Monetaria e Cambial de Macau Annual Report.

However, the overall impact on the BOP is difficult to be evaluated as the Government does not release estimates of cross-border income flows. The offshore bank assets, which can be treated as a kind of foreign investment by Macau's banks, should generate income inflows in the current account, offsetting fully or partly the capital outflows.

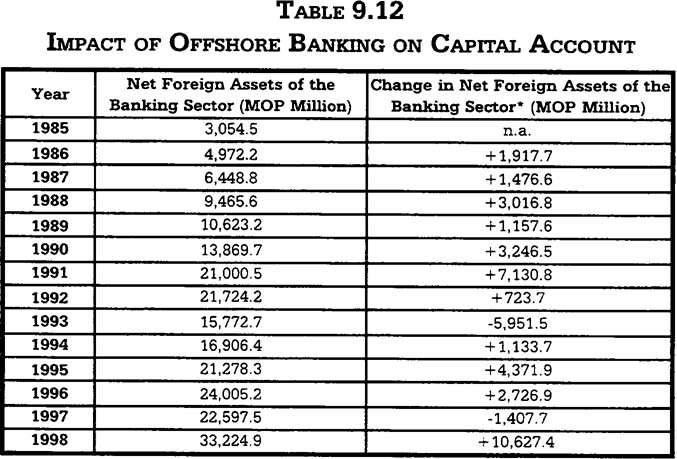

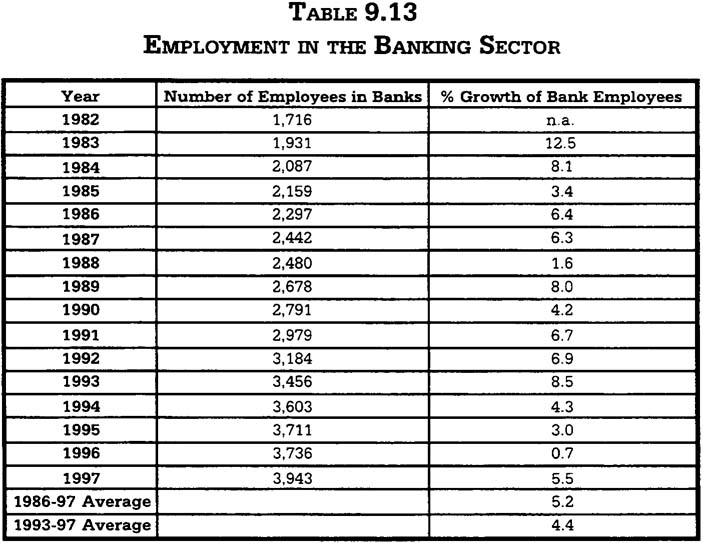

As a kind of economic activity, offshore banking is supposed to create employment opportunities for local workers. Table 9.13 presents the number of people employed in the banking sector during 1982-1997. The number was more than double in the period, with an exceptionally sharp rise in 1983, when the number of foreign banking institutions rose markedly from five to 13. In 1997, the employment in the banking sector accounted for about 1.9 percentof the total labourforce. This in itself is not a substantial contribution to local employment. Between 1986 and 1997, the average annual growth of bank employees was 5.2 percent, compared to 16.2 percent growth for total bank assets and 16.8 percent growth for foreign assets of the banking sector.

Source: Underlying data from various issues of Instituto Ernisor de Macau Report and Accounts and Autoridade Monetaria e Cambial de Macau Annual Report.

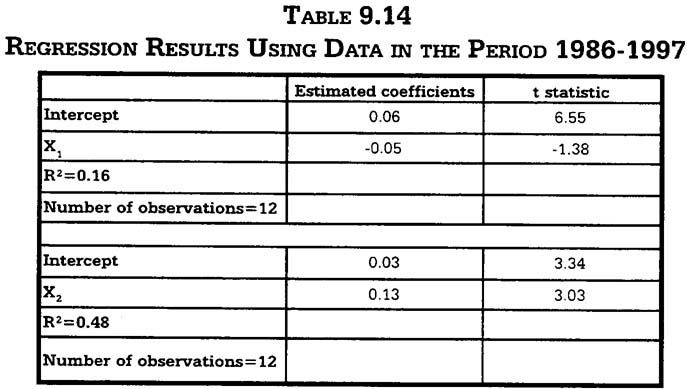

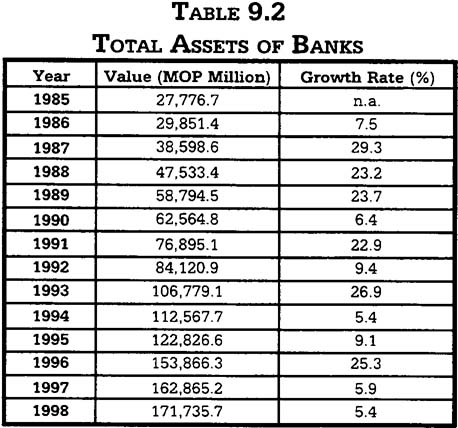

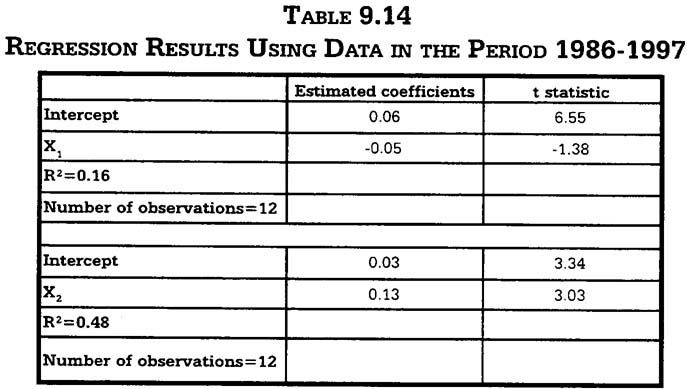

A simple regression analysis based on the data in the time period of 1986-1997 is conducted to test the hypothesis that offshore banking business does not help create jobs in Macau's banks. Regression analysis is a statistical technique that can be used to develop an equation to estimate how the variables are related. The regression equation is specified in the usual form of a linear relationship in which a particular independent variable is postulated as the cause of the variation of the dependent variable. It is mathematically shown as:

y=α+βx1

yis the growth of bank employment (dependent variable), x1 is the growthof foreign assets (independent variable), α is the intercept, and β is the change in the dependent variable corresponding to the change in the independent variable.

Meanwhile, we also estimate the regression equation with the growth of domestic assets (x2) as alternative independent variable. It is important to note that foreign assets and domestic assets represent offshore banking business and onshore banking business respectively. Table 9.14 presents the results of regression of the dependent variable. The independent variable,growth of foreign assets (x1), is insignificant at the 0.05 level using a twotailed Student-t test. The respective R2 indicates that the regression model only explains 16 percent of the variability of the growth of bank employment.On the other hand, the growth of domestic assets, which represents the growth of onshore banking business (x2), is significant at the 0.05 level (with t-statistic=3.03). Estimated coefficient for x2 is of theoretically correct sign. The marked increase in R2 also supports a higher level of explanatory power of the regression model.

Source: Author's calculations.

The regression results indicate that offshore banking business has little impact on employment in Macau. Bank employment tends to benefit from the growth of domestic banking business, rather than the growth of offshore banking business. This indicates the low requirement of extra human resources for the offshore business, as well as the integration between onshore and offshore banking in Macau.

Finally, the impact of offshore banking on government receipts should not be significant given the small number of offshore banking units in Macau.According to the current tax regulations, the major government receipts from the only offshore bank in Macau are establishment fee and operation fee. Based on the territorial source principle, incomes derived from pure offshore transactions is non-taxable.25

Overall, there is little evidence for significant benefits to the real sector generated by the offshore banking business in Macau. This bleak interpretation should be partly explained by the lack of data for a thorough study. Econometric analysis shows that it is the domestic banking business, rather than the offshore banking business that contributes to the growth of jobs in banks in Macau. This probably reflects the Territory's over-emphasis on the simple form of offshore interbank transactions, which creates little value added in the production of financial services. The relatively low value-added production of the banking services should also be attributed to the missing of established financial markets in Macau. The public debate over upgrading the industrial structure in Macau that currently puts much emphasis on the manufacturing industry should therefore extend to the financial sector.26

The active offshore business and the high integration of onshore and offshore banking sectors have another implication for the domestic economy.In 1998, 34.8 percent of foreign assets were financed by domestic funds. In fact, foreign assets are always larger than foreign liabilities in the local banking system. Macau's banking sector is therefore a net creditor to the rest of the world or serves as a capital exporter. It implies that local banks do not have enough business opportunities to fully utilize their funds domestically or are simply unwilling to extend loans to local business and individuals. Continued existence of excessive domestic funds, in the absence of capital controls, thus supports the expansion of foreign placements. This, however, would undermine the banking sector's primary role in promoting Macau's economic growth and development. At this juncture, the business scope of domestic banking must be widened to ensure promising prospects for the banking sector as well as the Macau economy.

NOTES

1 Deutsche Bank, A.G. has announced to close its branch in Macau. Other than the 22 commercial banks, the Caixa Economica Postal is also a credit institution within the local banking system.

2 See Chapter 4.

3 In fact, the Fu and Ko families of Tai Hing Company were involved in An Ho business.The Ko family, for example, owned the Fu Hang An Ho located in the commercial area of Macau,Avenida Almeida Ribeiro. The exclusive right of gold trading was transferred to Wang On Company in the 1960s, and granted to Woo On Company in the early 1970s.

4 The Government's reliance on import tax on gold illustrated the significance of gold trading. Until the early 1970s, receipts from tax on gold import accounted for over 10 percent of total fiscal revenue. Gold was mainly imported from Europe, melted into bars and then reexported to China, Hong Kong and Southeast Asian countries. The business came to an end when Hong Kong liberalized gold trading in 1973.

5 The Bank of Canton was remaned the Security Pacific Asian Bank in 1991 and the Bank of America in 1994.

6 The Nam Tong Bank was remaned the Bank of China, Macau Branch in 1986.

7 See Chapter 8.

8 The Banking Supervision Division was established in 1964.

9 The capital requirement was raised to MOP100 million in 1993 when the Government replaced Decree Law No. 35/82/M with Decree Law No. 32/93/M (Legal Framework of the Financial System).

10 Offshore banking involves raising funds from non-residents for lending to other nonresidents. See the later part of this Chapter.

11 They included the failure of the Pacific Bank in 1983, bank runs on Luso International and Tai Fung in 1983, and on OTB and Wing Hang in 1984.

12 As a comparison, the insurance sector - the other less important type of financial business in Macau has reported losses since 1997 due to the large provisions and claims on motor vehicle insurance. The sector, as a whole, recorded a loss of MOP1 million in 1997 and a loss of MOP36.4 million in 1998.

13 Interest incomes are derived from interest margin between loans and deposits.

14 As a result, the debt paper is not issued by the government treasury.

15 Assuming that the market risk is not significant.

16 Monetary institutions are depository institutions, which can create means of payments or money. Other monetary institutions are commercial banks, development banks, postal savings banks and the monetary authority.

17 For a detailed analysis of the Offshore Banking Ordinance, see Chan (1999b).

18 See IEM Annual Report 1988, p.90.

19 See analysis in Chapter 4.

20 This echoes our argument expressed in Chapter 6 that Macau is basically a capital exporter.

21 For a detailed analysis of foreign bank activity in Hong Kong, see Chan (1997a).

22 It is due to visits by foreign businessmen, offshore bank customers and conference participants.

23 Adjusted to exclude net interest receipts or "expenditure on financial intermediation services". See Chapter 2.

24 The decrease in net foreign assets in 1993 was due to the strong domestic demand for external interbank funds. See AMCM Annual Report 1993, p.91. The reduction in 1997 shouldbe attributed to a substantial capital loss of Macau banks' financial investment abroad in the aftermath of the Asian financial crisis. See AMCM Annual Report 1997, p.85.

25 For a description of Macau's tax system, see Noronha (1996).

26 For details of the debate over the upgrading of Macau's industrial structure, see for example, Ieong (1998) and Yan (1998).