CHAPTER 4 THE MONETARY SYSTEM

THE SILVER STANDARD

Before the pataca, the Macau currency, was created in 1906, Macau's monetary standard had been based on silver, as was the case for Mainland China and Hong Kong. Silver assumed the major monetary role, while a relatively small value of copper was used for retail transactions. The precious metal was also the typical exchange unit for foreign trade in the entire Asia.

The most popular silver money for daily transactions in the pre-pataca era included Chinese silver ingots and coins, Mexican Eagle dollars, silverbacked pangtans (cash deposit certificates) issued by An Ho1, and silverbacked banknotes issued by Hong Kong banks. China, Hong Kong and most other Asian territories were using the same kind of silver money as their currencies. The money supply of Macau was then determined by the amount of silver stock in the Territory. The simple currency and exchange arrangement was consistent with the basic requirements of mercantile and trade at that time.

THE SILVER STANDARD AND THE ESCUDO STANDARD

In 1905, the Macau Government granted the Banco Nacional Ultramarino (BNU) the monopoly right to issue legal tender banknotes in pataca denominations. The first batch of one-pataca and five-pataca banknotes, valued at 175,000 patacas in total, was circulated in Macau on the 27th of January 1906.The name "pataca" was derived from the then popular silver coin in Asia, the Mexican eight Reales, known in Portuguese as the Pataca Mexicana (Ma 1987).

The pataca initially had a guaranteed silver content in the sense that it was redeemable in silver coins on demand. Despite the convertibility-intosilver commitment, the banknotes were not 100-percent backed by silver reserves. The BNU was only required to hold monetary reserves, in the form of deposits with the Bank of Portugal, bullion, interest-bearing securities and foreign exchange, equivalent to at least one third of the banknotes in circulation (King 1953).2 Monetary reserves were recorded in the asset account of the note-issuing bank, but under the custody of the monetary authorities inPortugal. The pataca issue thus provided significant seigniorage gains for the note-issuing bank. To forestall over-issue, the quantity supply of pataca banknotes was ultimately approved by the Government. Meanwhile, the BNU was required to maintain a solvent position with liquid assets to sufficiently cover the sum of the banknotes in circulation, ordinary deposits and any other credits payable on demand.

As silver was also the monetary standard of Hong Kong and Mainland China, Macau was in fact in the same currency area with Hong Kong and Mainland China. The issue of patacas by a Portuguese-controlled bank was mainly an endeavour of the Portuguese Government to exercise its ruling authority in Macau. In view of the close relationship between Macau and Hong Kong/China, the attempt to introduce the gold-based escudo in Macau was bound to fail. Instead, the Portuguese Government chose to establish an official link between the pataca and the escudo, at a rate of one pataca equivalent to five escudos. The free issuing environment also played a role in motivating the creation of the pataca. As mentioned in the outset of this chapter,some large An Ho were issuing silver-backed pangtans which circulated as a medium of exchange. It was therefore a natural development for the BNU the only commercial bank in Macau then, to participate in the issue of silverbacked banknotes.3

Meanwhile, the pataca and the Hong Kong dollar were exchanged at the rate of 1:1 in the open or unofficial market as the two currencies had the same silver content. Unofficial market transactions were those not passing through the BNU.4 The exchange brokers in Macau made use of the facilities of Hong Kong to trade Hong Kong dollars. The official link to the escudo was of little economic meaning then, and the fixed exchange rate between the escudo and the pataca was only applied to a limited number of official transactions through the BNU.

Since its first issue in 1906, the pataca has never been successfully deterred by foreign currencies, in particular the Hong Kong currency, from sharing its monetary role in Macau. In 1929, the Macau Government prohibited the circulation of foreign currencies in the Territory. This attempt to strengthen the monetary status of the pataca, however, did not succeed. Silver-backed Hong Kong banknotes and Chinese silver coins continued to circulate widely in the Territory for practical trade purpose, notwithstanding that they were not accepted in payment of taxes, rates or other government accounts. This reflected the reality that the economy of Macau was closely related to the economies of Hong Kong and Mainland China.

As the Nationalist Government in China and the Hong Kong Government abolished the Silver Standard in 1935, the monetary role of silver in Macau started to deteriorate. Meanwhile, the Hong Kong dollar was shifted to aSterling Exchange Standard under a currency board arrangement. Despite this monetary reform in Hong Kong, the exchange rate stability between the pataca and the Hong Kong dollar in the open market remained intact.

THE GOLD EXCHANGE STANDARD AND THE ESCUDO STANDARD

During the period of Japanese occupation in Hong Kong between December 1941 and August 1945, the Hong Kong dollar rapidly lost its value,as the Japanese introduced the military yen. The Government, to a certain extent, installed the pataca as a dominant currency in Macau. Stern enforcement and substantial reserves of both silver and foreign currencies made the tightly controlled pataca the popular means of payments during wartime.

After the Second World War, the Hong Kong dollar quickly restored its reputation in Macau. It was widely accepted as a means of payments in the Territory, especially after the serious over-issue of the Chinese currency issued by the Nationalist had caused the Macau public to completely lose confidence. To maintain a stable value against the Hong Kong dollar practically became the prime monetary policy for Macau to enhance the continued acceptability of the pataca. Meanwhile, major industrialized countries were eager to establish a stable exchange rate system for rebuilding the world economy. Following the United Nations Monetary and Financial Conference,held in July 1944 at Bretton Woods, 44 major countries agreed to adopt a generalized fixed exchange rate system under Article IV of International Monetary Fund (IMF) Agreement. In 1946, a worldwide Gold Exchange Standard was formally in place. Each member country was required to set a par value for its currency to be expressed in terms of an intervention currency or gold.Macau, adhering to the Escudo Area with a realigned official rate of one pataca exchanged for 5.5 escudos, then maintained a fixed exchange rate relationship with all leading currencies (King 1953). As the Hong Kong dollar was linked to the sterling since 1935, the pataca became indirectly linked to the Hong Kong dollar under the Bretton Woods System.

Until 1977, the pataca was officially linked to the escudo, but in practice maintained a stable exchange rate relationship with the Hong Kong dollar.Some examples revealed the pataca's de facto adherence to the Hong Kong dollar. In 1949 and 1967 when the Hong Kong dollar followed the pound sterling to devalue, the pataca also devaluated in order to maintain a stable exchange rate with the Hong Kong dollar. In March 1973 Portugal notified the IMF to float the escudo, as the Bretton Woods System was on the verge of collapse. The pataca then started to revalue against the weakening escudowith the objective to maintain a stable exchange rate relationship with the Hong Kong dollar. To strengthen the pataca's exchange rate stability against the Hong Kong dollar, the Government required the note-issuing bank to hold a "minimum level of foreign exchange reserves", which mainly comprised of Hong Kong dollars.5 Commercial banks and the S.T.D.M. were required to exchange foreign currencies generated by export activity for patacas with the note-issuing bank, which managed Macau's official reserves.

THE HONG KONG DOLLAR STANDARD AND THE UNITED STATES DOLLAR STANDARD

Following the Carnation Revolution in Portugal in April 1974, the escudo had been under severe pressure to depreciate. The left-wing government brought a large part of the economy under state control, and introduced various welfare and income re-distribution schemes. Inflation was serious and Portugal's balance of payments was deteriorating. Between the end of 1974 and the end of 1976, the escudo depreciated by 28 percent against the US dollar, reaching the rate of 31.549 escudos per one greenback. The pataca correspondingly depreciated against the Hong Kong dollar due to its official link to the escudo. In 1976, the exchange rate of the pataca against the Hong Kong dollar reached an all-time low of 1.21. The local inflation was mounting and the daily business activity was seriously disturbed.

On 7 April 1977, the Macau Government decided to officially link the pataca to the Hong Kong dollar at a central rate of MOP1.075:HKD1, with a fluctuation margin of± 1%.6 The Macau currency left the Portuguese currency area after 71 years of official link to the escudo. To enhance the official link,the Government correspondingly tightened the exchange regulation. Other than the commercial banks and S.T.D.M., business entities such as local travel agencies, which earned foreign currency revenues, were required to exchange part of their foreign exchange earnings for patacas at the official rate with the note-issuing bank.

A major institutional reform was implemented in 1980, when the Government transferred the exclusive right to issue patacas from the BNU to the newly established Instituto Emisor de Macau (IEM).7 The BNU became the sole "agent" bank of the IEM in issuing banknotes. To exercise its authority over money issue, the IEM assumed the liability of note issues and took the responsibility to manage the official reserves. The requirement of net foreign reserves holding was initially set at no less than 50 percent of the sum of pataca currency issue and other pataca-denominated sight liabilities of theIEM.8 The Government has gradually adjusted the foreign reserve requirement ratio upwards to 90 percent. Since 1987, the net official reserves have exceeded 100 percent of IEM's sight liabilities in patacas.

Two failed attempts to set the pataca at par with the Hong Kong dollar,after the establishment of the official link to the Hong Kong dollar, confirmed the pataca's vulnerable status as a circulating currency in Macau and its subordination to the Hong Kong dollar.

On 31 December 1978, the Government announced a 1:1 exchange rate between the pataca and the Hong Kong dollar. Banks immediately stopped exchange transactions in response to the public's massive switch from patacas to Hong Kong dollars. As a result, the Government was forced to realign the fixed exchange rate to MOP1.038:HKD1, with a fluctuation margin of± 4%, on the first trading day of 1979. Between 1979 and 1983, the Government adjusted the fixed exchange rate in several occasions, with an objective to revalue the pataca against the Hong Kong dollar. On 6 June 1983, the middle exchange rate reached MOP1.03:HKD1.

In the summer of 1983, Hong Kong encountered a currency crisis. On 24 September, panic selling of the Hong Kong dollar drove the exchange rate to an all- time low of USD1:HKD9.6 - a depreciation by 13 percent within two days. In response to the crisis, the Macau Government announced on 26 September to fix the pataca's exchange rate at par with the Hong Kong dollar,which again caused an extensive selling of patacas for Hong Kong dollars.Similarly, the Government was forced to return to the original rate of MOP1.03:HKD1 on the following trading day.9

Another institutional reform further strengthened the pataca's link to the Hong Kong dollar. In 1989, the Autoridade Monetaria e Cambial de Macau (AMCM) was established to replace the IEM.10 The right to issue pataca banknotes was returned to the BNU under a currency board-styled arrangement.11 The BNU became the agent bank of the Macau Government, rather than the monetary authorities, in money issue. The note-issuing bank12 was required to pay the AMCM an equivalent amount of Hong Kong dollars at the fixed rate for non-interest bearing Certificates of Indebtedness (CIs) as legal backing for the note issue.13 The issue of the pataca is 100 percent backed by foreign assets.14 Meanwhile, the AMCM took the IEM's position as Macau's central depository of foreign reserves.As the Hong Kong dollar has been linked to the US dollar under similar currency board arrangements after the October-1983 currency crisis, the pataca has been indirectly linked to the US dollar.15 Since then, the objective of Macau's monetary policy has been explicitly defined by the AMCM as the maintenance of exchange rate stability between the pataca and the Hong Kong dollar.

THE CURRENCY BOARD SYSTEM

The central bank note-issuing system is the most popular monetary system, under which the central bank takes up the responsibility to maintain the value of national money by controlling its supply. As mentioned in the previous section, Macau has a different monetary system called the currency board system (CBS), which has attracted much international attention after the Mexican financial crisis in 1995 and the Asian financial crisis in 1997/98. Under the CBS, the authority to issue legal tender notes is still vested in the Government, which may authorize designated banks or specialized non-central-bank organizations (so called currency boards) to perform the function of its agents in the currency issue.

Currency boards are operated without a central bank and by nature a fixed exchange rate monetary system. They have a statutory obligation to issue and redeem their currency on demand against reserve money at a fixed rate of exchange and without limit. The note issuers have no authority over the quantity of money in supply. They held international reserves equal to at least 100 percent of their currency liabilities when valued at a fixed exchange rate. With a 100 percent reserves backing, the currency board assures the full convertibility of the local currency into specified reserve money at a fixed exchange rate. The CBS is therefore widely regarded as an effective institutional arrangement to enhance the robustness of fixed exchange rates.

The CBS automatically performs a counter-cyclical function. When the economy is in recession, demand for imports will decrease but demand for exports will increase. The economy will experience a balance of payments (BOP) surplus and an inflow of foreign currencies. As a result, the supply of domestic money will increase. On the contrary, inflation will bring a BOP deficit and a contraction of money supply. Therefore, the money supply is ultimately determined by the BOP, and no government agent has an authority over money.

A notable feature of the Macau system is that the currency board (AMCM)does not issue legal tender notes.16 The BNU and the BOC have been authorized to perform the function of the government agent in the issue of the banknotes. CIs held by the note-issuing banks could be redeemed for Hong Kong dollars at the fixed rate from the AMCM. To strengthen the Hong Kong dollar link throughout the entire banking system, the AMCM has stood ready to buy and sell Hong Kong dollars against the pataca within a very narrow margin centered at the fixed rate.

According to AMCM Annual Report 1998, the AMCM held foreign exchange reserves, the net of short-term foreign currency liabilities, equal to106.6 percent of the pataca liabilities when valued at the fixed exchange rate of MOP1.03:HKD1.

ONE COUNTRY, TWO CURRENCIES

As argued'in Chan (1997b) and Chan (1999c), Macau and Hong Kong offer a unique case study of a monetary system. They have had a separate currency from their sovereign powers for many decades. It is what is called the "one country, two currencies" model, which provides an alternative perspective to the widely discussed "one currency for many countries" model in Europe. In the case of Macau, in particular, the renminbi or escudo is only treated as a foreign currency. Patacas are issued by two commercial banks under the CBS, and circulate as the legal tender in Macau. Currency and exchange arrangements are, of course, interrelated. Two currencies are not truly independent with each other if they are linked with a fixed exchange rate. Since 1977, the pataca has been officially linked to the Hong Kong dollar, and the current fixed rate of MOP1.03:HKD1 has existed for more than 15 years. As the Hong Kong dollar is linked to the US dollar, the pataca actually follows the greenback to float against the renminbi and escudo. Macau therefore provides a valuable, and rare, real-world example that national authorities, given enough justification, are willing to sacrifice at least part of their monetary autonomy.

Although the Basic Law (Article 108) guarantees the continued circulation of the pataca under the one country, two systems commitment,the survival of patacas is not completely free of challenge. On 14-15 May 1999, the AMCM, with the official support of the People's Bank of China and the Bank of Portugal, organized a conference on central banking policies in Macau. During a discussion, some scholars queried the economic justification to maintain a separate currency in Macau. One interesting proposal is the substitution of Hong Kong dollars for the pataca as legal tender in Macau.

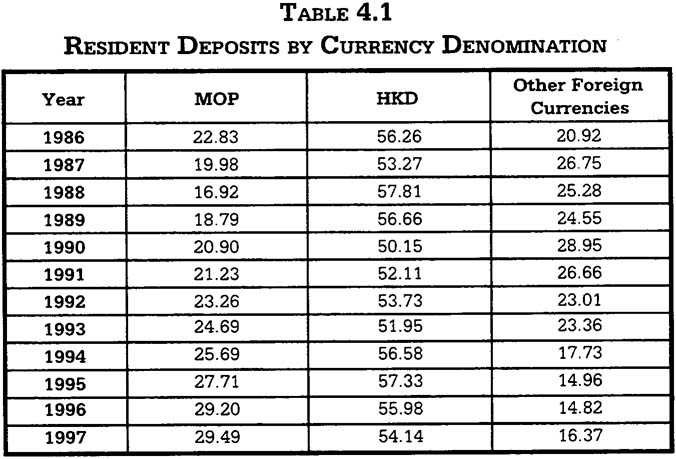

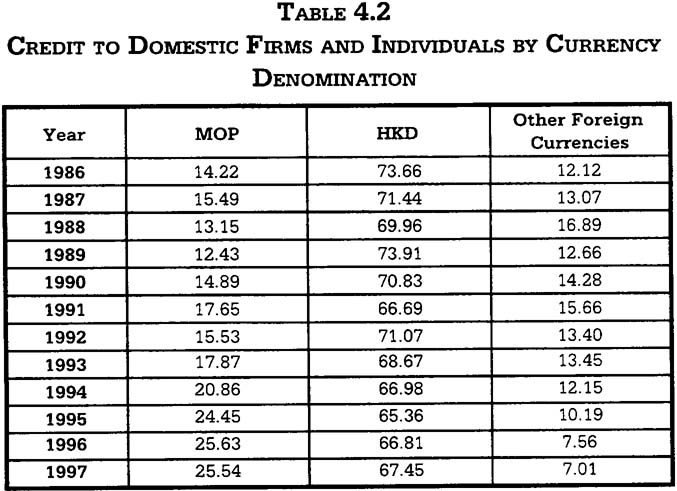

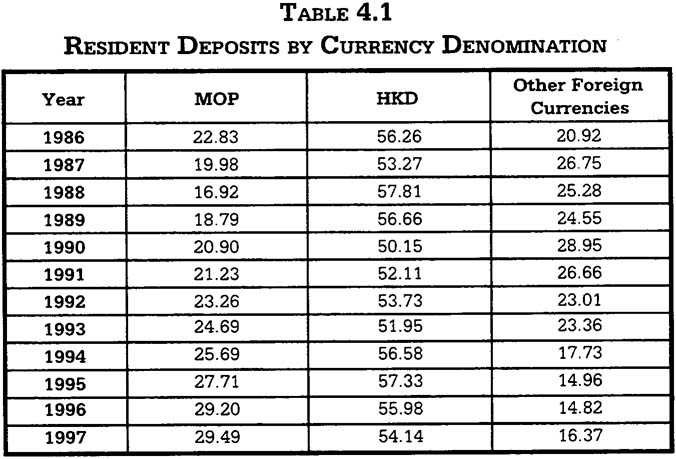

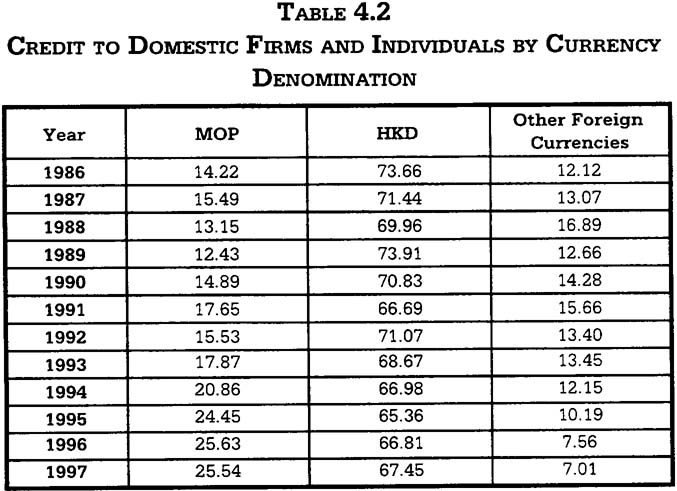

The acceptance of Hong Kong dollars by the Macau people is certainly non-arguable. Notwithstanding the legal support to the circulation of the pataca17, currency substitution18 is obvious in Macau. Over half of the resident deposits with Macau's banks are now denominated in Hong Kong dollars while pataca deposits only account for less than 30 percent of the total (Table 4.1). More than 60 percent of domestic credit are denominated in Hong Kong dollars (Table 4.2). One recent estimate puts the circulation of Hong Kong dollar banknotes in Macau to be 1.4 times higher than the pataca banknotes (Siu 1998).

Unit: as a proportion of total (%)

Source: AMCM Annual Report, various issues.

Unit: as a proportion of total (%)

Source: AMCM Annual Report, various issues.

From a historical perspective, however, the pataca has been viewed as a realization of the local authority and Macau's autonomous identity since its first issuance in 1906. As the renminbi is not fully convertible19, the continued circulation of a separate convertible currency in the Macau SAR is necessary for the maintenance of the Territory's current open economic system.

Macau's persistent adherence to Hong Kong undoubtedly makes little economic sense for it to have a completely independent currency vis-a-vis the convertible Hong Kong dollar. As discussed in previous sections, the economic logic has worked well to maintain a stable exchange relationship between the Macau pataca and the Hong Kong dollar for almost a century. The official link to the Hong Kong dollar in 1977 and the establishment of the currency board system in 1989 further consolidated such relationship. As Friedman (1973) argues, "two currencies with different names are essentially unified with a fixed rate of exchange between them". In fact, Macau and Hong Kong have been in monetary union for a long period of time. The elimination of patacas from circulation will make little economic difference and hence should only add little benefit to the Macau economy.

In the author's opinion, as long as the seigniorage20 gain is positive, it is still worthwhile to maintain a separate monetary identity for the autonomous Macau SAR. It should also be noted that the seigniorage gain is positively related to the amount of pataca issues and hence the survival of the pataca should be ultimately determined by the preference of the Macau people for using and keeping this currency.

NOTES

1 An Ho are native Chinese financial institutions. They are engaged in banking businesses including lending, deposits, foreign exchange, bullion dealing and remittance.

2 The one-third reserve requirement or two-thirds fiduciary issue was also adopted by the Bank of England in the early 1900s.

3 Adopted from Pangtans issued by An Ho, pataca notes initially had a corresponding attached sheet kept by the issuing bank. The sheet was for verification purpose when the notes were demanded for redemption into silver.

4 The BNU remained the only commercial bank in Macau until 1971. See for example, Siu (1998) or Chan (1999a).

5 Referring to Law No. 24/73 and Law No. 28/73.

6 Referring to Portaria (Executive Order) No. 39/77/M.

7 The IEM was established as a financially independent, autonomous public enterprise within the Government, to perform certain central banking functions.

8 Referring to Decree Law No. 63/82/M, net foreign exchange reserves were defined asthe primary cover of sight (current) pataca liabilities of IEM. Primary reserves mainly included bullion, foreign currencies and short-term high-rated foreign securities. Secondary reserves were mainly pataca-denominated assets held by the IEM.

9 It was estimated that the banking sector lost over MOP2 million.

10 Referring to Decree Law No. 39/89/M.

11 The currency board system used to prevail in most British colonies or protectorates.For an introduction to the currency board system, see, for example, Walters and Hanke (1989).Hong Kong has adopted the currency board system since 1983.

12 The Bank of China became the second note-issuing bank in 1995 after the Government's note-issuing agreement with the BNU expired on 15 October 1995. According to the agreement signed in 1995, each bank is responsible for half of the note issue.

13 In practice, the note-issuing banks obtain CIs from the AMCM in the following month,but not immediately after the note issue. Therefore, the value of CIs would not be exactly equal to "Currency in Circulation" in the consolidated balance sheet of the banking system.

14 This measure conforms to the Basic law, Article 108.

15 As a result, the note issuing banks are also allowed to exchange US dollar assets for CIs.

16 It however issues some low-value coins. Hong Kong's system shares the same feature.

17 Decree Law No. 16/95/M sets out some measures to strengthen the monetary status of patacas in Macau. They include: 1. All goods and services in Macau should have a pataca price; 2. Purchasers are free to pay for goods and services in patacas; 3. Patacas must not be rejected for settlement and clearing of domestic debts and other local transactions; 4. Payments of all locally issued credit cards should be settled with patacas; 5. Payments and receipts of public organizations must be in patacas.

18 Currency substitution on the demand side is defined as a tendency for a domestic currency to be systematically replaced by one or more foreign currencies in discharging normal monetary functions. See Jao (1993).

19 According to M.H. Lau, Deputy Governor of the People's Bank of China, the renminbi would become convertible in 2010, see Ming Pao, 25 May 1999.

20 Simply speaking, the excess of the face value over the cost of production of currency is seigniorage.