CHAPTER 1 ECONOMIC HISTORY AND MACROECONOMIC ENVIRONMENTS

WHAT KIND OF AN ECONOMY IS MACAU?

As a Chinese Territory under Portuguese occupation for more than 400 years, Macau, which comprises the Macau Peninsula, Taipa Island and Coloane Island, is situated on the western coast of the Pearl River in the southern part of China. In 1998, a population of 430 thousand inhabited the land with an area of only 23.6 square kilometres. The enclave's annual gross domestic product (GDP) valued at MOP54.6 billion (USD6.8 billion), which was equivalent to about half of that of Beijing, the capital of the People's Republic of China, but only four percent of the GDP of its neighbouring city, Hong Kong. Since 1994,Macau has been a high-income economy under the World Bank's classification. Its GDP per capita was over MOP128,100 (USD16,055) in 1998, and ranked fourth in Asia, just behind Japan, Hong Kong and Singapore.

Notwithstanding this phenomenal economic performance, Macau hardly caught the world's spotlight, until the emergence of the 1999 issue in the late 1990s. On the 20th of December 1999, the People's Republic of China resumed the exercise of its sovereignty over the tiny enclave. Since then, Macau has become the second Special Administrative Region (SAR) of China.1 The relative neglect to Macau should be attributed to its small size, and the weak presence of international business in the Territory.

But in fact, Macau has unique economic features and history, which provide a valuable real-world reference for many economic studies. As one of the two SARs in China, Macau is allowed to retain a different economic system from its sovereign power for fifty years. Under the pioneering practice of the "one country, two systems" policy, Macau maintains its own currency unit and independent public finance. In terms of land area, Macau is the second smallest independent economy in the world, just behind Monaco. The tiny territory has the third largest GDP per capita in the world among those small economies with a population less than one million. It is identified as one of the 53 "geographically scattered countries" in the world engaged in offshore banking in the authoritative New Palqrave Dictionary of Money and Finance.The Territory also has the highest cross-border population mobility rate and the highest population density in the world when compared with all the otherterritories reporting national data to the World Bank. All these intriguing economic phenomena and their implications will be extensively discussed in the various chapters of this monograph.

In recent years, Macau has been labeled by some local economists as a "mini" economy.2 While mini-economy is certainly not an established terminology in any literature of economics, it does reflect some basic economic features of Macau. In particular, a mini-economy should meet the following three criteria. First, its population does not exceed one million. Second, it has independent economic institutions such as an independent monetary authority or is responsible for its own public finance. Finally, it has international recognition as an independent economic area. International recognition can be shown in the acceptance of international organizations such as membership to the World Trade Organization and the Bank for International Settlements.

In 1998, the World Bank identified about 200 independent economies in the world. 59 of them with a population not exceeding one million are potentially classified as mini economies. They are mostly high-income or upper medium-income economies with an annual per capita income higher than USD3,116.3 Low-income mini economies with a per capita income of USD785 or less are mainly located in Africa. In terms of income per capita, Luxembourg - a mini economy with a population of 416 thousands - is the wealthiest economy in the world. Another mini economy, Iceland, is also one of the world's top-ten affluent economies. Among those economies reporting national data to the World Bank, Macau ranked the third just after Luxembourg and Iceland. Despite their relative affluence, mini economies only share a small proportion of the world's economic capacity. They account for no more than five percent of the world's GDP, population and area.

While some mini economies are abundant in natural resources, Macau has few basic resources except its strategic location as the "gate" of South China. It represents a typical example of laissez faire comparable to Hong Kong, which is reputed to rest upon its free-market environment to sustain its economic growth. Macau has a simple and relaxed tax system, no meaningful capital control, and minimum government influence in economic activity.4With small internal markets and limited resources, it heavily counts on foreign markets, capital and supplies. The Territory's merchandise trade relies on the US, EU and China, and its invisible trade relies on the Greater China Region (Mainland China, Hong Kong and Taiwan). China, Hong Kong and Portugal are reported to be the dominant outside investors in Macau.

Macau never carries on an active policy of macroeconomic management.Its currency, the pataca, is linked to the Hong Kong dollar, the currency of its closest economic partner, Hong Kong, under a currency board arrangement.As a result, the Government has no autonomy over domestic money supply.Monetary aggregates are determined by the balance of payments and local interest rates, which closely follow Hong Kong's interest rates. On the fiscal front, Macau's fiscal budget has been mostly in balance. Due to the large import leakage and the small multiplier effect, any discretionary changes in government expenditure will have little stabilizing effect on the economy. Until the 1980s, the Macau Government even avoided to play a role in such critical areas as education, housing, infrastructure development, banking regulation and export promotion.5

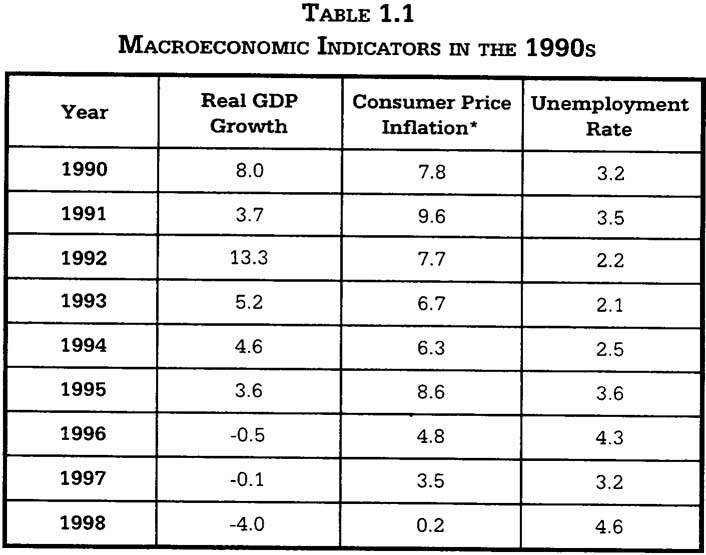

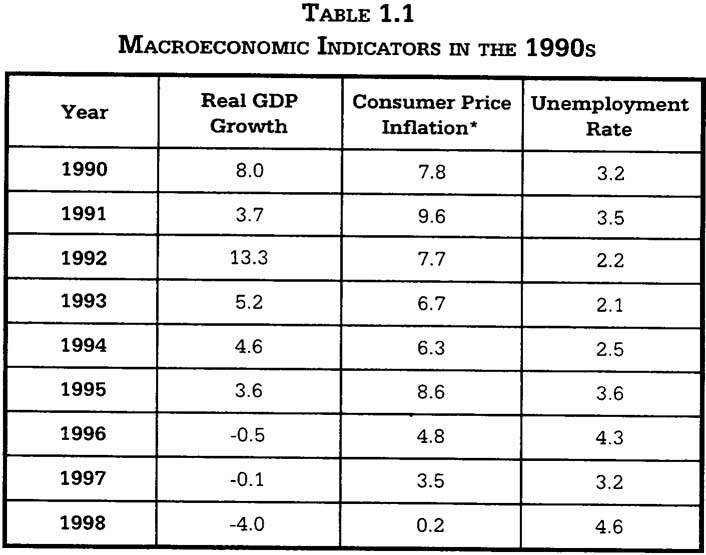

Unit: Percent

Note: *measured by global index.

Sources: Estimativas do Produto InternoBruto 1982-1998; Indice de Precos no Consumidor,various issues; Anuario Eststistics, various issues.

THE ANCIENT MACAU

Macau has an economic history of about 450 years, which is linked with Portuguese occupation. When the Portuguese arrived at Macau in the 16thcentury, it was a barren-fishing village with a population of about 400.6 Between 1573 and 1848, the Portuguese paid an annual ground rent of 500 taels (Chinese ounces) of silver to the Chinese Government to stay in Macau.7 In 1849, the Portuguese destroyed the Chinese customs post, repelled the Chinese officials in Macau and halted paying the ground rent to the Qing Government. In 1887, the Qing rulers signed the Treaty of Friendship and Commerce with the Portuguese Government, under which the Qing Government allowed the Portuguese to "settle permanently in Macau". In 1967, the Portuguese officially admitted Macau's special status as "Chinese Territory under Portuguese Administration". Finally on 13 April 1987, the Chinese and Portuguese Governments signed a Joint Declaration which determined Macau's reversion to Chinese sovereignty on the 20th of December 1999.

As the Portuguese promoted international trade, Macau had swiftly developed into a prosperous harbour city. Before the outbreak of the infamous Opium War in 1840, it remained the major gateway to China's interior market for western merchants and the centre for Euro-Asian trade. Portugal established various trading voyages from Macau to India, Japan, the Philippine Islands, Portugal and Mexico. The goods traded were mainly silk, silver, gold,tea and opium.8 In the 18th century, the Qing Government closed most ports in the coastal areas to foreign trade. The Portuguese were allowed to assume the role as a sole intermediary for restricted trade. Guangzhou became the only legal trading fair for international traders, and Macau was the entrepôt and the government-assigned place of temporary residence in China for Fankwae traders in non-trading seasons (Hunter 1911). The European companies rushed to establish their China-trade headquarters in Macau. With the rapid development of commercial activities, Macau's population increased markedly to 13,000 in the early 19th century.

After the Opium War, Macau experienced a full economic retreat. Most significantly, it failed to maintain its status as a leading commercial centre in Asia. Unlike its neighbouring city, Hong Kong, Macau was unable to establish a solid foundation for developing into a major economic area in Asia. By 1850, only two percent of foreign traders in China chose to reside in Macau.

We can identify five reasons for the decline of Macau as a major commercial centre in Asia since the latter part of the 19th century. These are:

1. Increased competition from other Chinese coastal cities. As a result of the Opium War, the Qing Government was forced to sign the Treaty of Nanking (1842) which caused the opening up of five coastal cities for foreign traders.Meanwhile, Hong Kong was ceded by China and became a British colony.The Nanking Treaty was the first of a series of unequal treaties, which completely opened China to the Western world. As many rivals emerged, Macauwas no longer the only gateway to the Chinese market for foreign traders.

2. Lack of transportation facilities. The maintenance of port facilities has always been a difficult and costly task for Macau as the outflow of the Pearl and West Rivers has frequently silted up its harbour. The port in Macau can not provide deep-water anchorage for ocean-going vessels, and hence is not attractive to international shipping lines.9 Hong Kong's Victoria Harbour,on the other hand, is a world-class deep-water port.

3. The decline of Portugal and the rise of Britain in the Far East. After the Opium War, the British had quickly replaced the Portuguese as the major power in Asia. With the support of British forces, trading activities were correspondingly moved to the British colony of Hong Kong.

4. Insufficient capital formation. Most economic benefits generated in Macau were not invested in local development. Fiscal resources of Macau were constantly being transferred to the Portuguese state or other Portuguese dependent territories in Asia such as Timor. Chinese businessmen in Macau also tended to transfer their profits to Hong Kong, which provided room for business expansion.

5. Over-reliance on China-related trade and commerce. Macau's early prosperity was solely built on China-related activities. An independent industrial or business base has never been established in the Territory. With the loss of China-trade activities to Hong Kong and other Chinese coastal cities, Macau hardly found other impetus to its economic and business growth.

As Macau lost its position as a leading trading entrepôt in East Asia, its trade activity speedily contracted and concentrated only in the neighbouring Guangdong and Hong Kong areas. Fishing re-emerged as a dominant economic activity in the Territory. In the early 1920s, over 70 percent of Macau's 84,000 residents were engaged in fishing activities. Meanwhile, some "anomalous" businesses started to develop to compensate for the constant loss of merchandise trade. The most notable one was the gambling business, which still plays a central role in guaranteeing the prosperity of Macau today. The Portuguese administration, in order to raise revenues, introduced a licensing system for Chinese gambling or fantan houses in the late 19th century. Over 200 gambling houses were required to pay gambling rent to the Government.Also based on revenue considerations, the Government granted concessions to nefarious businesses such as the opium and coolie trade, which remained active even until the Second World War. Signs of early industrialization were witnessed in the first few decades of the 20th century. Traditional craft industries developed during this period, which included matches, firecrackers, incense and fishing-boat building.

Macau became a haven of refuge during the Second World War due tothe Portuguese neutrality. As Japan's invasion of China proceeded, thousands of Chinese refugees fled from their homeland and arrived in Macau. Macau's population once reached an all-time high of 600,000.10 Many business firms in Mainland China and Hong Kong were relocated to Macau. The massive inflows of people and capital engendered a certain degree of prosperity in the beleaguered city.

After WWII, Macau's economy suffered from an immediate setback due to the return of refugees and business firms to the Mainland and Hong Kong.Macau's population dropped to 187,000 in 1950. The Korean War and the resulting United Nations embargo further dampened economic activities in the Territory.

THE MODERN MACAU

The Macau economy started a gradual recovery in the 1950s. Industrialists were attracted to invest in Macau as Portugal allowed Macau to export its products to all Portuguese territories with duty-free privileges.11 Modern light industries, notably textiles, were set up in this stage.

The gambling industry saw a major breakthrough in the 1960s. In 1962,the Macau Government granted an exclusive gambling licence to the Sociedade de Turismo e Diversoes de Macau (S.T.D.M.), which replaced the old-styled Tai Hing Company as the casino monopoly. The S.T.D.M. introduced westernstyle games and modernized the marine transport between Macau and Hong Kong by establishing the world's largest fleet of jetfoils. The new company proved to be successful in bringing millions of gamblers from Hong Kong every year. The gambling industry, through its significant tax contribution and re-investment commitments, provided the necessary capital for infrastructural development, which prepared for Macau's take off in the 1970s.

Many Hong Kong industrialists established their "out-processing" bases in Macau in the 1970s, with a view to take advantage of Macau's low-cost operating environment, surplus quotas under the Multi-Fibre Arrangement (MFA) and the Generalized System of Preferences (GSP) for tariff reduction granted by advanced countries.12 With the active participation of Hong Kong industrialists, Macau's merchandise exports were diversified from the merely Portugal-related market and introduced to the North American and western European markets. The number of manufacturing establishments increased from 172 in 1961 to 870 in 1978, and to 2,300 in the middle of the 1980s. In addition, there were over 1,000 unregistered family establishments for subcontracting works. The manufacturing sector accounted for about 40 percent of Macau's GDP in its golden period in the mid-1980s. Textiles and garmentswere the dominant items in Macau's manufacturing sector, and accounted for 90 percent of Macau's total visible exports in the late 1970s.

According to the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD), in the ten-year period ending 1981, Macau was one of the fastest growing economies in the world. Its annual economic growth averaged 16.7 percent, which was significantly higher than 10.4 percent in Hong Kong.Between 1983 and 1990, Macau's annual real GDP growth still averaged at a respectable level of 7.6 percent.

Meanwhile, the industrial take-off and the resulting rapid growth of trade and output generated strong demand for services, particularly for banking services. On the back of the promulgation of the modem banking ordinance in 1982 (Decree Law No. 35/82/M), the banking sector in Macau expanded rapidly in the 1980s. The number of banks increased from less than 10 in the 1970s to 21 at end-1980s. The services sector has assumed an increasingly important role in the domestic economy.

Since the early 1990s, Macau's manufacturing sector has been witnessed a consistent contraction, contrasted with an expansion in the gambling and related sectors13 and the rise of the financial and real estate industries. Reasons for the manufacturing decline are highlighted as follows:

1. Relocation of manufacturing establishments to low-cost production bases in South China.

2.Reduction in preferential treatments by western countries and restriction on transshipment to the US under the country-of-origin regulation.

3. Failure to enhance its competitiveness by quality and technological advancement.

The third reason has been argued to be most fundamental, Macau's manufacturing sector has long been dominated by small- and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs), which count on cheap labour for production, and were reluctant or unable to invest in quality.14 A small number of large factories are owned by Hong Kong industrialists who are primarily using Macau as a lowcost processing base and have little incentive to invest in quality in Macau.15The manufacturing contraction has caused a corresponding slowdown in visible export growth in recent years.16

With a consistent shrinking in manufacturing activities, Macau has undergone an economic transformation in the past few years, characterized by a structural shift towards the tertiary production. Its macroeconomic performance has been largely unsatisfactory, indicating that the transformation has encountered problems. As shown in Table 1.1, real GDP has been dropping and unemployment rate has been rising over the past few years. More evi-dence has been looming to support the argument that the current economic problem in Macau is more than a usual cyclical adjustment or a plain result of external disturbances. We will argue in the succeeding chapters of this monograph that the disappointing economic performance stems from a deviation of the mini economy from its optimal development path.

STRUCTURE OF THE MONOGRAPH

This monograph aims to provide an in-depth and comprehensive study of the Macau economy. It consists of 11 chapters, which cover all major aspects of Macau's economy. This chapter highlights Macau's unique economic features and briefly reviews its development history since its founding in the 16th century. It serves to explain how the economy has evolved into the present shape. With the macro framework in place, Chapter 2 further examines the relative importance of various economic activities in Macau. Macau is depicted as a services-based economy with a high development level by United Nations standards. As service production is labour intensive, Chapter 3 is devoted to a thorough discussion about labour utilization and human resources development in Macau. The controversial labour importation programme is also analyzed in detail in this chapter.

Policy is certainly a major determinant to performance in most economies including Macau. Chapters 4 and 5 investigate the monetary and fiscal systems, and the implementation of fiscal and monetary policies in the small enclave. In view of Macau's high degree of openness, Chapter 6 is assigned to analyze the Territory's external activity, including international trade and cross-border investment. Chapters 7-10 successively discuss developments of the four leading economic sectors (tourism and gambling, manufacturing,banking and property) in Macau. The four sectors have felt varying degrees of impact of the recession starting in 1996. Finally, an evaluation of the problem and prospects of Macau's economy at the dawn of the third millennium is given in Chapter 11.

NOTES

1 Hong Kong has been the Special Administrative Region of China since 1 July 1997.

2 See, for example, Ieong and Siu (1997).

3 See 1998 World Development Indicators, World Bank, pp. 32-33.

4 The Government has only regulated, in a rather relaxed manner, the most important gambling business and some public utilities.

5 The Government has modified this passive attitude since the 1980s. To indicate the change, the public sector's share of GDP increased from about 10 percent in the early 1980s to more than 20 percent in the 1990s.

6 Macau was the first outpost of Europe in East Asia.

7 The ground rent was initially paid to the Ming Government. In 1644, the Qing dynasty succeeded the Ming dynasty, and as a result, the ground rent was paid to the Qing authorities.

8 Opium was labeled as "western medicine" for trade at that time.

9 The Macau Government constructed a deep-water port and container terminal in Ka Ho of Coloane in 1991. The scale of the port, however, is hardly comparable to that of the Hong Kong port.

10 See Gunn (1996), pp. 123.

11 The privileges remained until the second half of the 1960s.

12 The low cost environment was attributed to the massive influx of Chinese immigrants and increased supply of basic goods from China.

13 They include hotels, restaurants and retail commerce.

14 See Sit (1990) and Cremer (1991).

15 This point will be further elaborated in Chapter 8.

16 The contraction of the export sector is the fundamental reason for Macau's prolonged recession in the second half of the 1990s. See our analysis in Chapter 11.