Bahá'í Population in Macau

T.Rex Wilson(Centre for Pre-University Studies University of Macau)

The Bahá'í religion has been established in Macau since 1954. Historical records and a recent membership survey show that the number of Bahá'ís grew slowly for many years, then increased to around two thousand. The popula-tion of the Macau Bahá'í community is mostly young and Chinese, and there are more men than women.

Historical Background

The Bahá'í religion, better known as Bahá'í Faith, began in 1844 when a Per-sian, known to his followers as the Báb (Gate), began to teach a new messianic religion in Iran. The first contact that this new religion had with China was in 1862 when a cousin of the Báb went to live in Shanghai for six years.1 It was dur-ing those years that the new religion carne under the leadership of Bahá'úlláh, who emphasised the oneness of mankind. It is from his name that the word Bahá'í (follower of Bahá) is derived.

The earliest Chinese followers of Bahá'úll~ah learned of the new faith while living overseas. The first known Chinese Bahá'í in China was Mr. Chen Hai An, who had accepted the new faith while living in the United States and returned to his native Shanghai in 1916. Another early Chinese believer was Mr. Liu Chan Song, who became a Bahá'í in the U. S. when he was a student at Cornell Univer-sity in 1921. He returned to his native Guangzhou in 1923, where he later became President of the Agricultural College of Sun Yat-Sen University. He introduced a prominent Bahá'í travelling teacher, Miss Martha Root, to President Sun Yat-Sen in 1924 and acted as interpreter during the interview. Dr. Sun listened with inter-est and asked her to send him two Bahá'í books. Later, Mr. Liu translated some Bahá'í books into Chinese and had them published in Macau.

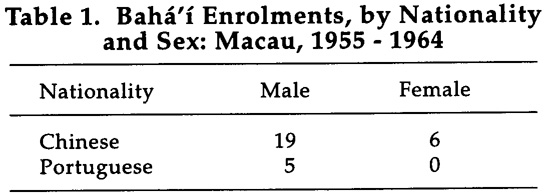

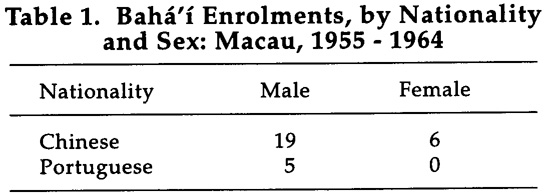

The first Bahá'ís to reside in Macau were three Americans who moved into the territory in 1954. They soon made local Chinese and Portuguese friends and taught the Bahá'í Faith to them. For the first eighteen years the religion grew very slowly. For example, there were only thirty enrolments in the first ten years. Twenty-five of these were Chinese and five were Portuguese. Many of the Chinese were teachers and all the Portuguese were in the army. Only six of the thirty were female and twenty-four were male (Table 1). None of them were native to Macau, and many soon moved away. In 1960 there were only Chinese Bahá'ís left in Macau.2

One of the early Bahá'ís in Macau, Mr. Cheong Siu Choi, translated several Baháí prayers into Chinese and published them in Macau in 1956. This was the first Bahá'ís prayer book ever published in Chinese. Another "first" achieved by Mr. Cheong was to be the first person to teach the new faith in Hainan Island, for which he received the honorary title of Knight of Bahá'úlláh.

Since there are no priests or clergy in the Bahá'í Faith, the activities of the community are co-ordinated and guided by a committee called the spiritual as-sembly, a body consisting of nine members who are elected democratically from among all the adult believers in the community. In the elections, which are held annually, there are no nominations and no electioneering. Instead, each member writes, on a secret ballot, the names of the nine believers he or she considers to be the best qualified from among the entire community. All the names on all the bal-lots are counted, and the nine individuais with the greatest number of votes are then expected to serve on the spiritual assembly without pay for one year. Since there must be exactly nine members elected to a spiritual assembly, a community with less than nine members cannot elect one.

In 1958 there were enough members to create the first spiritual assembly in Macau. Because the Bahá'í population in Macau was so transitory, there were always less than twenty members in Macau until 1972 when enrolments began to increase faster than losses to the community. In five of the years between 1956 and 1972 there were not enough members to re-elect the spiritual assembly. For the next twenty years after 1972 there was steady growth until the numbers grew to about two thou-sand believers. In 1972 a spiritual assembly was elected in Taipa, but was not re-elected again until 1984. The spiritual assembly of Coloane was formed in 1988.3

Bahá'í spiritual assemblies operate at three levels: local, national, and in-ternational. Today there are three local spiritual assemblies in the territory: Macau Peninsula, Taipa, and Coloane; and one national spiritual assembly, formed in 1989, which co-ordinates the activities of the local spiritual assem-blies and co-operates with other national spiritual assemblies. The national spititual assembly is accepted as a legal entity by the government of Macau. Bahá'í assemblies in most countries enjoy excellent relations with the civil authorities because loyalty to government, obedience of civil laws, and non-interference in political controversies are all articles of their faith. By 1992, there were 165 national spiritual assemblies around the world.4 Directing the work of the faith at the international levei is the Universal House of Justice, which has its seat in Haifa, Israel, and has infallible authority. All of theseinstitutions consist of nine members who are democratically elected.

The 1992 Survey of Bahá'í in Macau

In 1992 the national Spiritual Assembly of the Bahá'í of Macau compiled all of the information available on the members of the religion in Macau. The data was gathered from enrolment cards and mailing lists and was entered into a database. There were several hundred members whose address was unknown, due partly to the high mobility of people in Macau, and the information on these members was not included in the database. Moreover, not ali of the enrolment cards contain com-plete information, but the available information is nearly complete and includes data on, among other things, the address, age, sex, nationality, and languages spo-ken by each member. There is information on 1,117 from a total of about 2,000 believ-ers. The 1992 survey, then, is an uncontrolled sample, but has nearly complete infor-mation on most of the Bahá'í in Macau in 1992 and can give us a fair, though not exact, profile of the community as it was in the recent past.

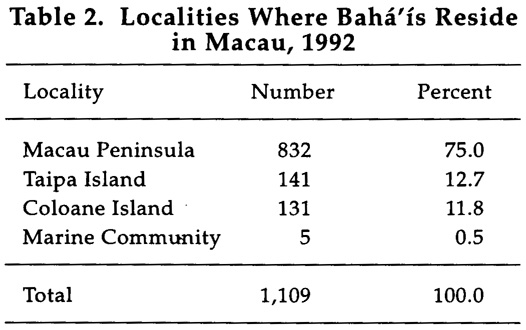

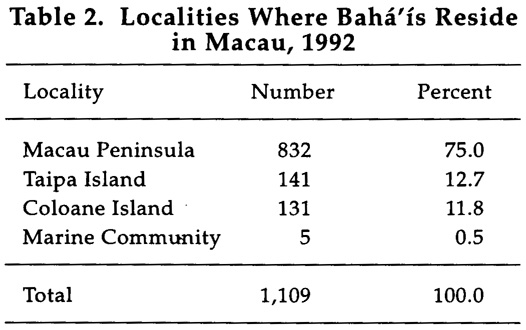

For administrative purposes, the database categorises members by.the commu-nity in which they resided. The four communities are Macau Peninsula, which is the largest one, Taipa Island, Coloane Island, and the Marine community of people who live on fishing boats. The distribution of members in these communities is shown in Table 2. It can be seen that the Bahá'í are spread throughout all parts of the territory. This is by design, since the Universal House of Justice urges believers to resettle in new locations so as to extend the influence of the faith to as many places as possible.

The total of somewhat less than 1,117 in this and other tables is due to the incomplete data on some individuals in the database, and only the known data is tabu-lated.

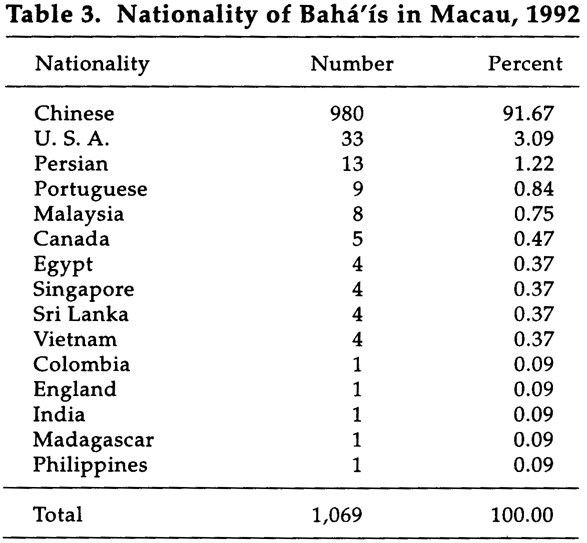

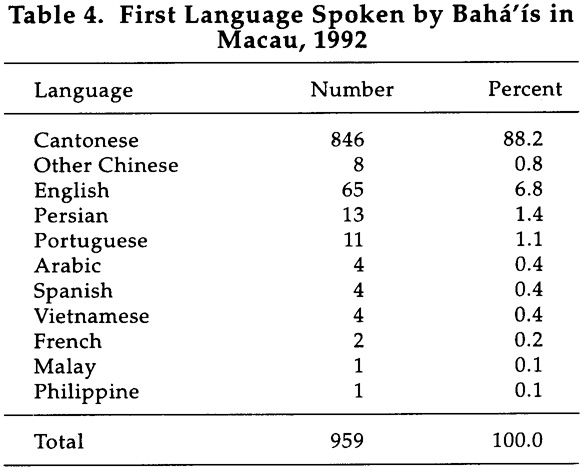

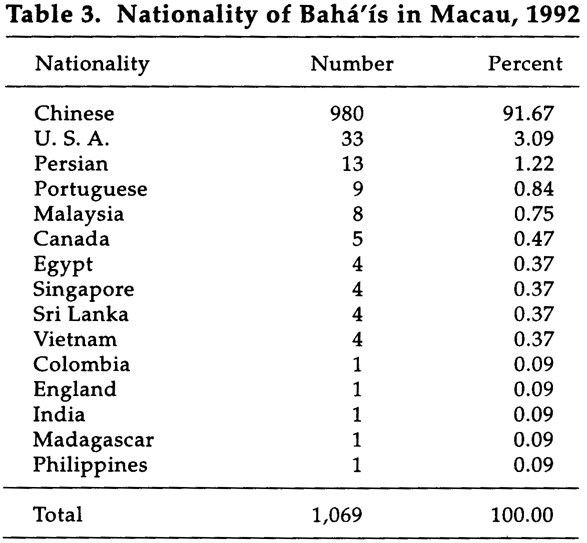

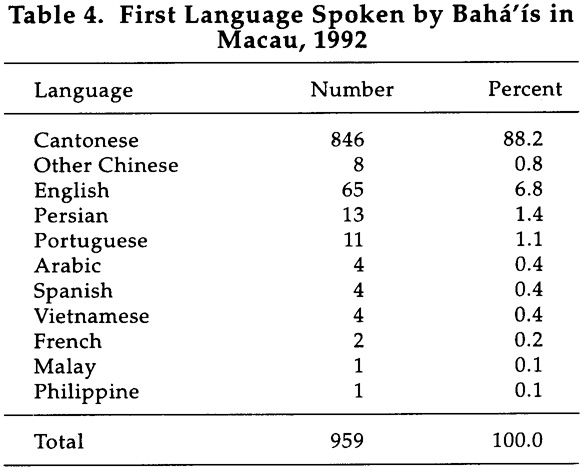

The overwhelming majority of Bahá'í in Macau are Chinese, as shown in Table 3, but there are also many other nationalities represented in the community. The Por-tuguese listed are mostly Macanese, and some of the members of other nationalities are overseas Chinese. The information shown in Table 4 on the first language spoken by members is less complete than the information on nationality, but reconfirms the picture of a predominantly Chinese community with an admixture of a variety of non-Chinese people. The presence of a number of Persian speakers is not surprising when we note that these people come from the country of origin of the Bahá'í Faith.

The Bahá'í are employed in diverse occupations. Many of the foreigners in this sample have come to Macau to help with Bahá'í social and economic develop-ment projects, such as the Bad? Foundation and the School of the Nations. Others help with Bahá'í activities in their spare time as they are self-supporting, employed in such occupations as engineering, computer sales and services, insurance sales, teaching, or clerical work. The Chinese members are also employed in a wide va-riety of occupations, including students, teachers, retail sales persons, managers, homemakers, and workers. Unfortunately, the data available on occupations is too sketchy to permit any generalisations to be made about the community. How-ever, one would not expect to find Bahá'í working in night clubs or casinos be-cause drinking and gambling are forbidden in their religion.

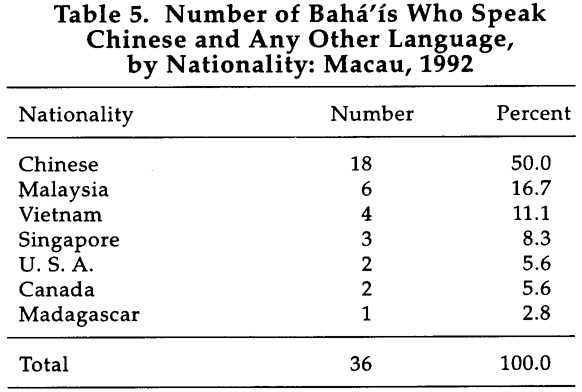

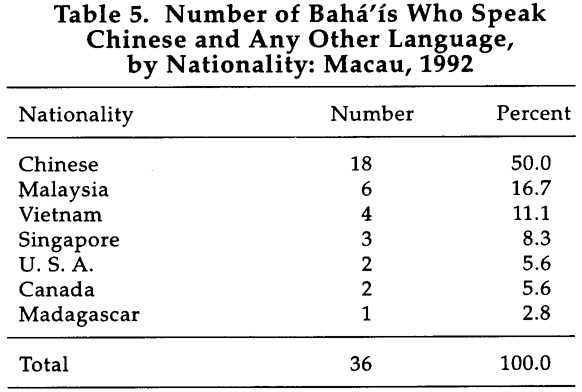

The ability of Chinese and non-Chinese people to communicate with each other depends largely on their ability to speak each other's languages. Table 5 shows the na-tionalities of those members in the sample who are known to speak a Chinese dialect,such as Cantonese or Mandarin, as well as a non-Chinese language. The numbers are not large. For example, only 1.8 percent of the Chinese members in the database are known to speak a foreign language, only two of the 33 Americans, and none of the Persians speak Chinese. The Malaysians, who are mostly overseas Chinese, the Viet-namese, and the Singaporeans do much better, but there are fewer of them than of the other nationalities. A lot of translating has to be done in Bahá'í meetings, and the bur-den of translation falls on the relatively few members who are qualified to do it.

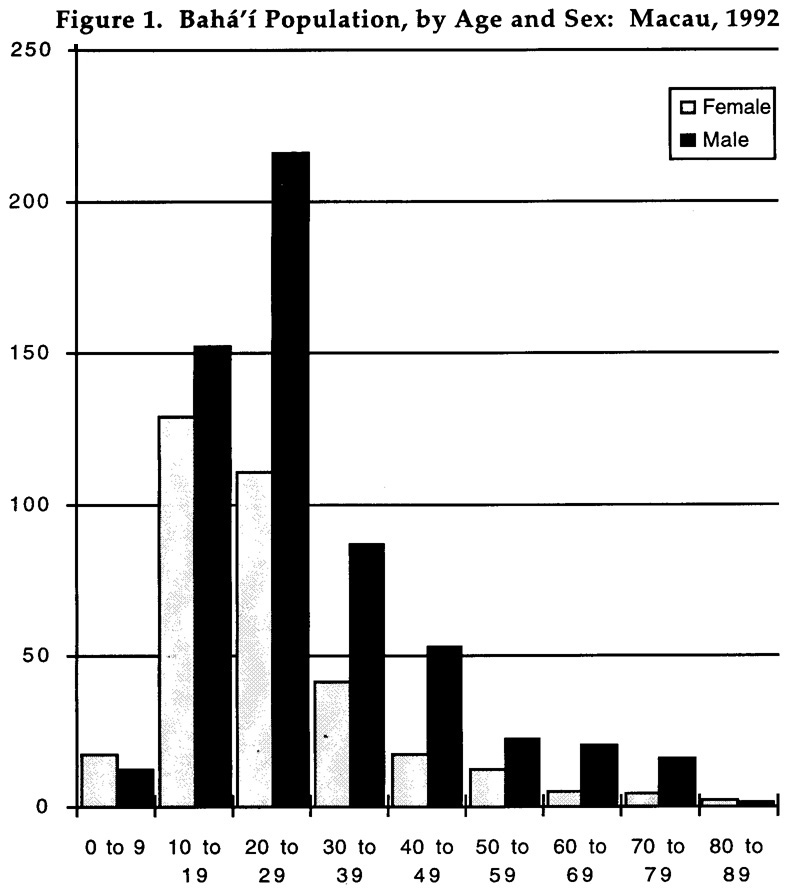

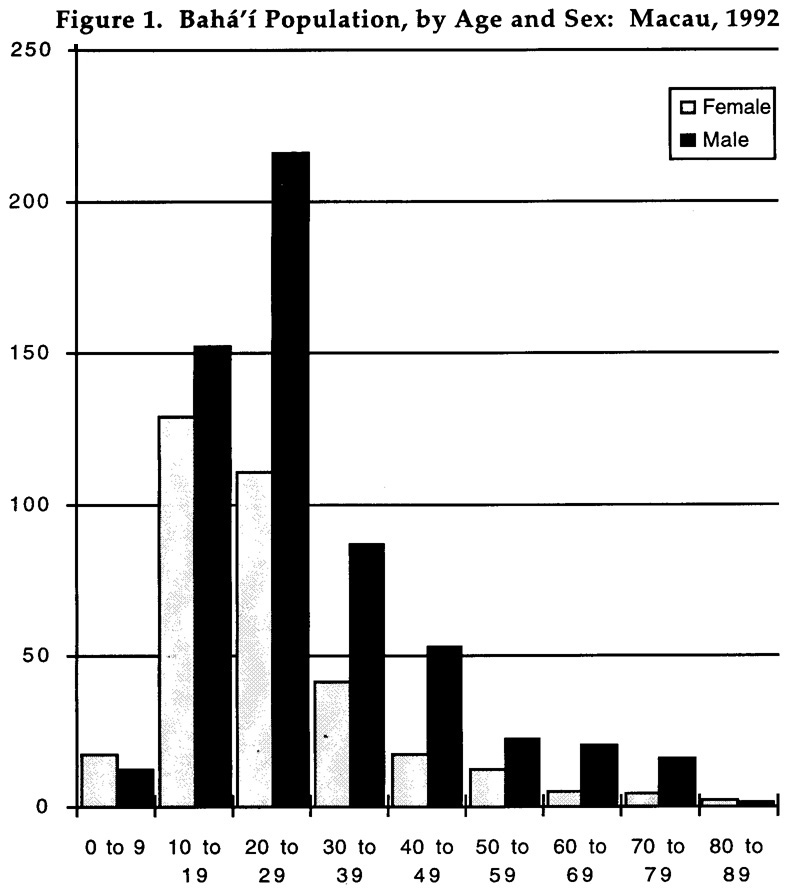

Figure 1 shows the distribution of Bahá'í in the survey by age and sex. It should be immediately obvious that this is not typical of the general population of Macau. One of the most striking features is that males outnumber females in ali age groups except for children less than 10 years old (a category which is probably under-re-ported) and those over the age of 79, whose numbers are insignificant (2 women, 1 man). Males total 579 (63 percent) of the 917 members of all ages whose age and sex are recorded in the survey. This seems odd because one might expect more women to be attracted to a religion that teaches the equality of men and women.

Another striking feature is the large number of young people. Nearly all the mem-bers are converts, and it is evident that the Bahá'í Faith has been more successful in attracting the young than the old. This is, perhaps, not surprising since nearly anything new is more likely to appeal to the young than to the old. The number of children in the 0 to 9 age group in this sample may be so small because few enrolment cards were filled out for the children of believers. It should also be noted that children less than fifteen years of age are not enrolled as members unless they obtain the consent of their parents.

Discussion

During the last forty years in Macau, the Bahá'í have grown into a commu-nity of about 2,000 members through the efforts of believers unaided by any min-isters or priests. They have elected their administrative institutions in the terri-tory, and have initiated projects of social and economic development.

It is clear from the 1992 survey that the vast majority of Bahá'í in Macau are young and Chinese. There are also members from many other countries, showing a remarkable diversity. It is curious that males outnumber females by nearly two to one. This is all the more intriguing when we consider that the sex ratio of Bahá'í in some other countries is reversed. For example, in the United States the Bahá'í women have been found to outnumber men by two to one.5 There may be some significant cultural factors that could account for these differences, and this would be an interesting question for further study.

Other matters for further study include the education, occupation, and socio-eco-nomic status of the converts to this new religion, and the factors that attract them to it.

Notes

1 Jimmy Ewe Huat Seow, The Pure in Heart: The Historical Development of The Bahá'í Faith in China, Southeast Asia and Far East (Mona Vale, Australia: Bahá'í Pub-lications Australia, 1991), p. 24.

2 Barbara R. Sims, The Macau Bahá'í Community in the Early Years (Tokyo: Barbara R. Sims, 1991).

3 Robin Taylor, "History of the Faith in Macau" (unpublished manuscript in the archives of the Spiritual Assembly of the Bahá'í is of Macau).

4 Bahá'í World Centre, The Six Year Plan 1986 - 1992: Summary of Achievements (Universal House of Justice, 1993).

5 Peter Smith, "The American Bahá'í Community, 1894 - 1917: A Preliminary Survey," in Moojan Momen (ed.), Studies in Báí and Bahá'í History, vol. 1, (Los Angeles: Kalimat Press, 1982), p. 121.