Political Culture in Macau

Liu Bolong and Herbert Yee (Faculty of Social Sciences and Humanities University of Macau)

In 1991, a group of teaching staff and students of the Faculty of Social Sci-ences at the University of Macau carried out a survey of the political culture of the Macau people. Based on the survey results, this paper seeks to analyse the status and the characteristics of the political culture in Macau.

This paper points out that three types of political culture (the parochial, the subject and the participant cultures) coexist in Macau. Those who are totally ignorant of the political system and the political process and those who take an active part in the political activities occupy a small percentage of the populace in the territory. Most of the local people hold a mixed political cul-ture.

Political Culture in Macau

Political culture is an important component in the study of any government because it has a tremendous impact on the performance of that government. Po-litical culture refers to people's ideas, values and opinions in respect of the politi-cal system. There have been numerous publications in the West on this topic; in Hong Kong and Taiwan scholars carry out continuous and systematic surveys on the issue and publish their findings yearly. The purpose of the present study is to fill the gap in Macau by surveying and analysing the political culture of the local residents.

From 1991 to 1992, a group of teaching staff and students of the then Faculty of Social Sciences at the University of Macau conducted a survey on the political culture of the Macau people.1 With the financial support of the University, the Instituto Cultural de Macau and the cooperation of the Macau Statistics and Census Depart-ment, we successfully interviewed 664 people. The response rate was 65 percent.

This paper seeks to analyse Macau's political culture according to Almond and Verba's model, which is widely accepted and applied by social scientists to study the political culture of a particular country. The model categorises the po-litical culture along three dimensions: cognition, affection and evaluation.2 How do citizens of a country know about the political objects?3 What are their feelings towards and opinions of the political objects of a country? The model also divides the political objects into three: general political system, input and output objects (mainly government institutional arrangements, government policies and per-formance) and self as a political object. We use Almond and Verba's model to de-scribe and analyse Macau's political culture.

Macau has been ruled or jointly ruled by the Portuguese for over 400 years. Macau's general political system today is a Governor-centred one supported by the Legislative Assembly with respect to legislation. Since the 1974 Portuguese revolution, Macau has become an administrative entity with a high level of au-tonomy in administrative, economic and financial' management and legislation. A limited democratic structure has been established with three partly directly-elected institutions: the Legislative Assembly, the City Council and the Islands Council. Among Macau's population, ninety-seven percent are Chinese, the others being Portuguese and Macanese. Most Chinese are from the Fujian and Guangdong Prov-inces of the PRC. There have been two main waves of immigration to Macau, the first being in the Anti-Japanese War in the 1930s, when the population reached more than three hundred thousand. The second wave came at the end of the 1970s, when China pursued an open-door policy and many new immigrants arrived in Macau. By the end of the 1980s, around one hundred thousand people had settled in Macau. In 1991, the Macau government decided to extend an amnesty to illegal immigrants, and more than thirty thousand people acquired a legal right to stay. The political culture of the Macau people is thus deeply influenced by Chinese culture, especially the sub-cultures of Fujian and Guangdong Provinces. At the same time, the Portuguese have ruled Macau for over 400 years, and the Western political culture represented by Portugal has also had a strong impact on the local people, especially on those Chinese bom and educated in Macau.

General Political System

For the purpose of the 1991-92 survey, we designed a set of questions to probe the public's orientation towards the general political system in Macau, including the Governor, the Legislative Assembly, the judicial system, and the Basic Law for the future Macau Special Administrative Region. These questions also included the main aspects of the political culture: the local people's cognitive, affective and evaluative attitudes toward the general political system.

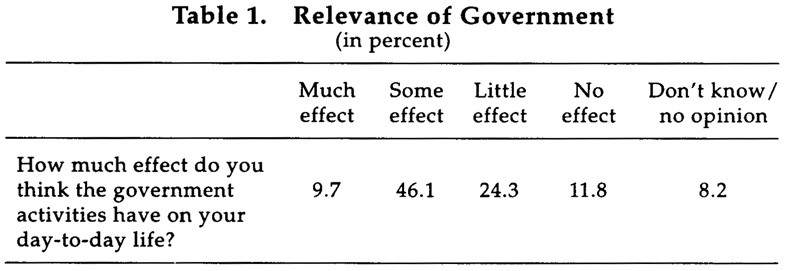

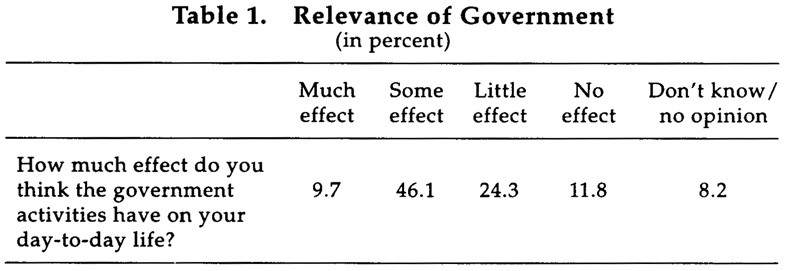

When asked if they felt the government had anything to do with them, 55.8 percent of the respondents believed that government activities had great or some effect on their day-to-day lives, while only 24.3 percent felt very little effect and 11.8 percent no effect at all (Table 1). Our findings suggest that the Macau Chinese do take politics seriously. Naturally, we expect people who take politics seriously to be also concerned about public affairs. Most public affairs are disseminated through the mass media. Macau has one television broadcasting company and one radio station. There are two main Chinese newspapers, the Ao Men Daily and Hua Qiao Bao, and about a dozen small daily or weekly publications. When we asked local people whether they often read newspapers, watched TV or listened to ra-dio, 41.8 percent of the respondents followed news 'every day' and 24.9 percent 'often' followed news in the media. This indicates that Macau people are concernedabout public affairs. Yet, at the same time, we were shocked by the fact that 53.6 percent of our respondents did not know the new governor's name or got it wrong. We were equally disappointed to find that there was low interest and willingness among the Macau populace to discuss public issues. Only 5.4 percent of the re-spondents said they often discussed government issues with their families or friends. Some 22.8 percent occasionally did so. More than 70 percent seldom or never discussed public issues with others.

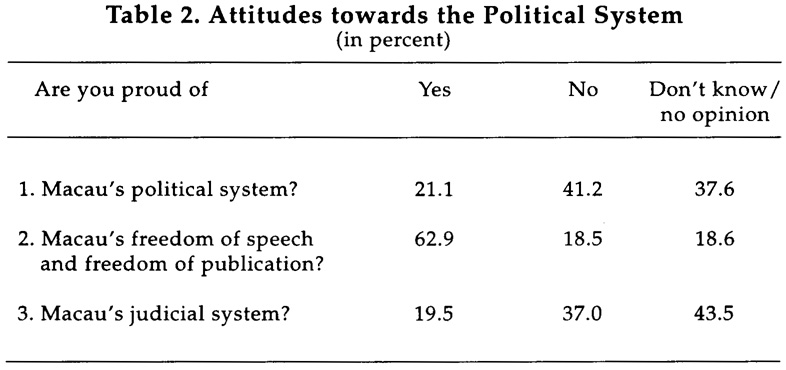

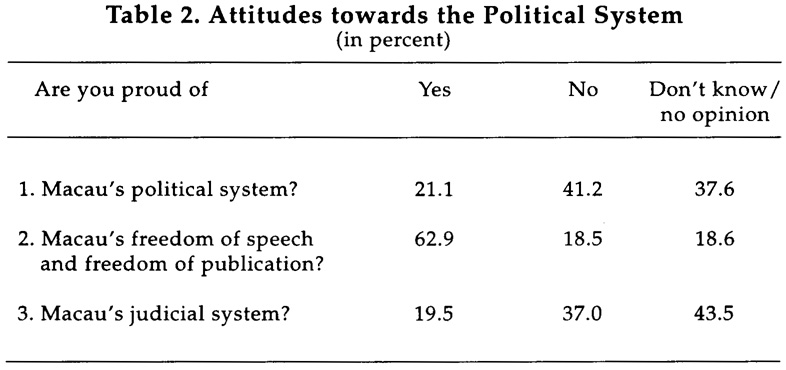

We designed another set of questions to probe Macau people's feelings toward the general political system. Here again we detected a mixed picture. On the question of Macau's general political system, only 21.1 percent of the respondents took pride in the political system (see Table 2). On the question pertaining to Macau's judicial system, we found almost the same picture: only 19.5 percent of our respondents took pride in the judicial system. Our inter-viewees, however, responded favourably to Macau's freedom of speech and freedom of publication: 62.9 percent of the respondents took pride in the en-clave's freedom of speech and freedom of publication. The question arises of why the people of Macau have seemingly contradictory feelings toward the political system itself and the essential elements of that system. We believe this is due to the general lack, or at least the severe paucity, of understanding of the political system. Quite a large proportion of Macau residents could not grasp the main points of their general political and judicial systems. They misunderstood the general political system as something concrete: social and physical security or city garbage collection, the inefficiency of the government or corruption problems. Although not necessarily trivial, the above problems do not reflect the true structure and general performance of the Macau politi-cal system. As for their low affection towards the general judicial system in Macau, corruption is to be blamed. As for the freedom of speech and publica-tion, Macau people have the freedom to express different opinions and ideas through newspapers, radio and television where they can express their dis-pleasure and complaints against the Macau Government. They can also dem-onstrate, assemble and publish newspapers with different opinions. MostMacau residents are immigrants from China, and carry the indelible memory of what happened during the Cultural Revolution and other turbulent years, and it is thus hardly surprising that they are quite satisfied with the freedom of speech and publication to be found in Macau.

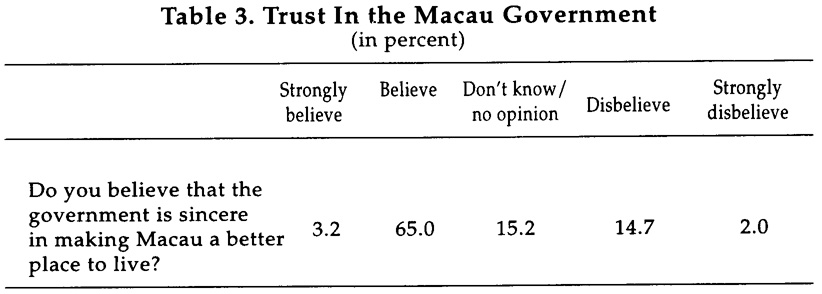

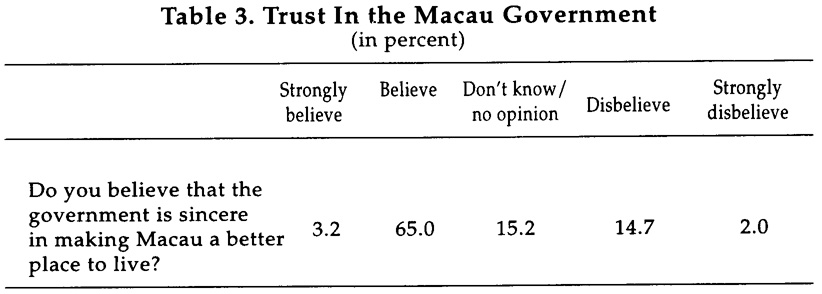

As for the public's feelings toward the Macau government, two questions were designed to probe citizens' trust in the government (see Table 3). When people were asked if they believed the Macau government was sincere in trying to make Macau a better place to live, 68.2 percent gave positive answers; only 16.7 percent did not believe in the government's sincerity, while 15.1 percent had no opinion.

However, few believed that Macau government officials were quite able and responsible at work. Why are there two conflicting results? In our in-depth inter-views, we found that responses on the question of trust in the government's sin-cerity to be based on Macau's economic success: large-scale projects, high-rise com-mercial and residential buildings, and rapid growth-rate. This underlines the in-fluence of a traditional Chinese belief, stressing the government's responsibility to care for the material well-being of the people. Secondly, they pointed to a nota-ble improvement made by the government in the process of democratisation and its willingness to listen to public criticisms: opening up new channels for accept-ing public opinions, introducing direct elections to the Legislative Assembly as early as 1976, and appointing an anti-corruption commissioner in 1991. As for the second question, the citizens derived their impressions from watching TV and read-ing newspapers, where inefficiency among civil servants or corruption among government officials are widely reported.

Orientations towards Input and Output Objects

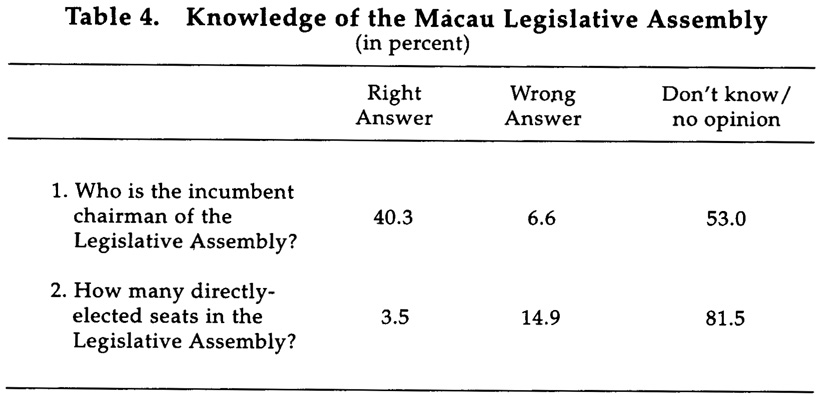

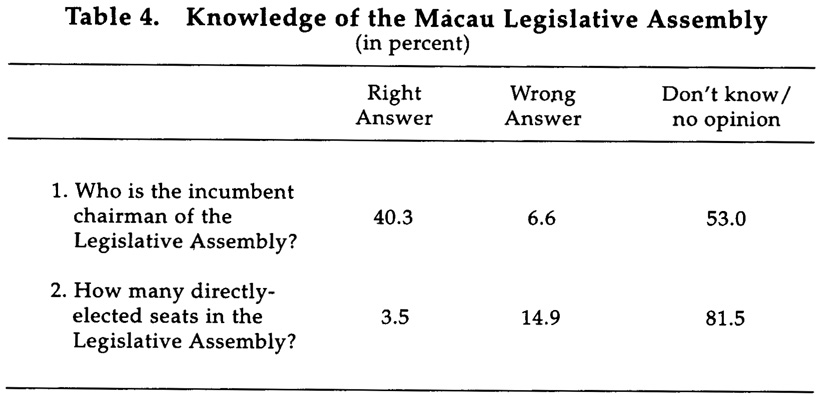

According to Almond's model, one of the main ways of measuring politi-cal culture is to find out how well citizens know the input and output parts of the political system. The input objects refer to the main institutions of gov-ernment, including the executive, legislative and judiciary. The output objects refer to the main policies and decisions made by the government, and their implementation. As far as the main institutions are concerned, we simply asked questions about the Macau Legislative Assembly and the City Council. Most people's cognition of their Legislative Assembly was very poor. The first ques-tion asked was who was the then chairman of the Legislative Assembly; only 40.3 percent of the respondents were able to name Carlos d'Assumpção, while 59.6 percent did not know his name or got it wrong. This is quite disappoint-ing considering that Carlos d'Assump玢o, who died in April 1992, was a very active public figure who frequently appeared in the local media. The second question concerned the number of directly-elected seats in the Legislative As-sembly. Things here are even more disappointing. Only 3.5 percent of the re-spondents answered the question correctly, while 96.5 percent did not know the answer at all or got it wrong (see Table 4). The above findings suggest that the people of Macau are in general apathetic towards the input objects. The answer lies partly in the influence of a traditional culture which gives little weight to a citizen being conversant with his government's institutions; and partly to the fact that the government has not put enough effort into civic education. The third question concerned people's attitudes towards local elec-tions to the Legislative Assembly and the City Council. Here we found quite positive responses. A majority (54.4 percent) of the respondents believed that elections in Macau were meaningful or very meaningful. Since positive atti-tudes towards elections are essential for the smooth operation of a democratic society, the reflection of this opinion is important to political development in Macau. Although limited in power, the Legislative Assembly has done a rea-sonably good job in overseeing the government, that is, acting as watchdog to look after people's interests. The main concern of the local people is to havean institution that they can trust and through which their complaints and griev-ances can be forwarded to government officials. The directly-elected mem-bers are particularly active in both scrutinizing government policies and help-ing citizens to solve problems pertaining to their livelihood. The local peo-ple's appreciation of this performance is reflected in generally positive feel-ings towards local elections.

We analysed attitudes toward output objects along both cognitive and affec-tive dimensions. First, we asked two questions about governmental policy on the Economic Housing Plan and on the privatisation of the city's garbage collection. On the Economic Housing Plan, more than half of the respondents did not know one had to live in Macau for at least five years to qualify for the plan or gave wrong answers. On privatisation, things were better: over 66 percent of the peo-ple had heard of the policy. Generally speaking, Macau citizens have a better un-derstanding of policies than of the system itself.

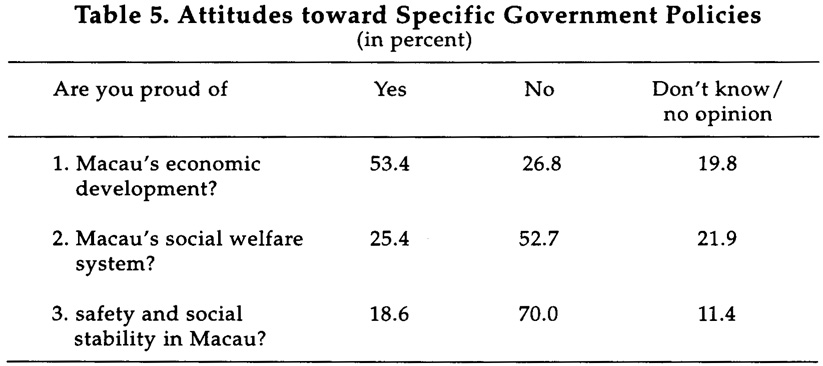

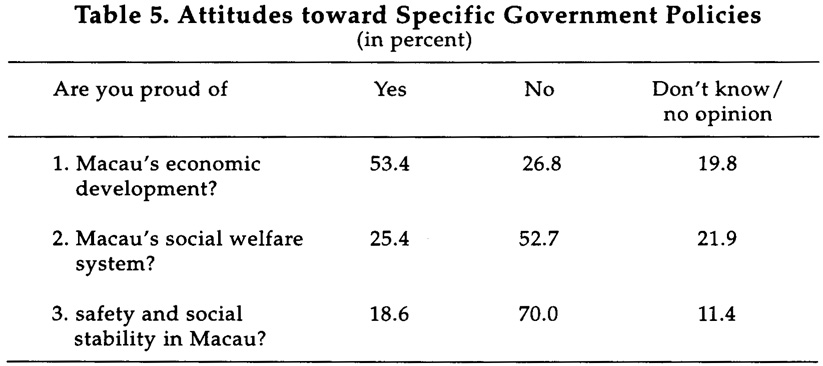

To discover the citizens' evaluation of policies, we first asked them about Macau's economic progress (see Table 5). A majority of the respondents took pride in Macau's economic development. Why did we register such favour-able responses? Macau has achieved economic prosperity over the last two decades, and the per capita GDP is now the fifth highest in Asia. One indica-tion of the booming economy is the enclave's numerous construction sites. And many new immigrants have a better standard of living here than in China;they are well-satisfied with their status. The second question concerned Macau's social welfare policy: only a quarter of the populace were satisfied with the government's performance, and 52.7 percent of our respondents took no pride in Macau's social welfare system. Social welfare policy has always been a headache for the Macau Government. The large-scale influx of immi-grants from China in the last decade has put heavy pressure on the system.The government has increased its social welfare expenditure over the years but cannot keep pace with population growth. The figure still represents a much lower ratio compared to that of the developed countries.4 As for their affection towards safety and social stability, our respondents showed their dis-satisfaction. The influx of large numbers of illegal immigrants from mainland China and frequent robberies have made safety in Macau a worrisome prob-lem. On the output side, our findings suggest a mixed picture. Macau peo-ple's degree of satisfaction swings, depending on concrete policies and their implementation. But, generally speaking, they have a higher degree of con-cern towards output objects. On the above three questions, only 20 percent of our respondents had no opinions or did not know. They seem to have more knowledge of output than of input objects.

Political Orientations towards Self As Objects

According to Almond & Verba's model, the main difference between subject and participant political cultures lies in the ways citizens regard their rights and obligations in political participation. How do they believe that they should par-ticipate in the political and social activities? Are they confident that their partici-pation can influence government policies? These are two crucial questions. As far as Macau is concerned, how citizens view their functions in political participation is of great importance to any future political structure in the territory.

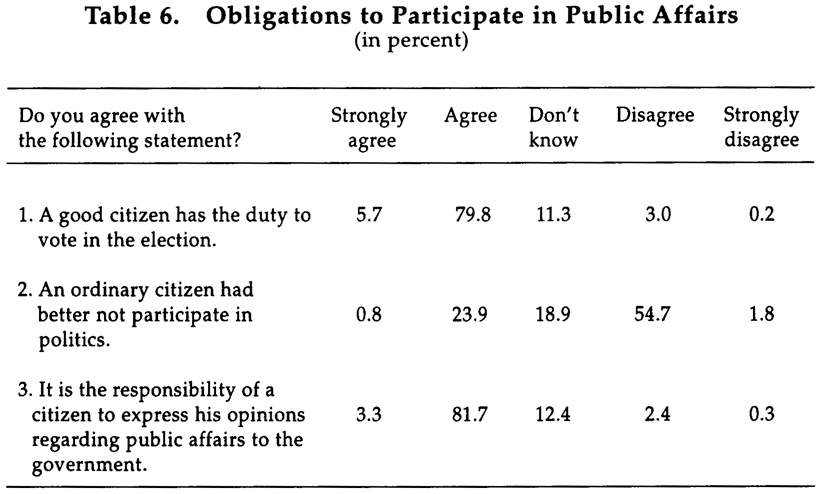

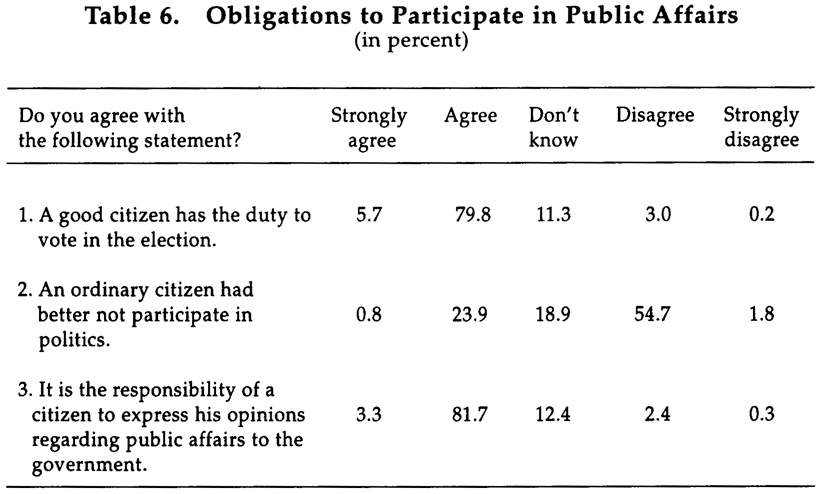

First of all, how do Macau citizens recognize their rights and obligations in political participation? Our survey indicates that they generally hold positive at-titudes towards their roles in political activities (see Table 6). When our respond-ents were asked whether they agreed that a good citizen had the duty to vote in elections, 85.5 percent agreed or strongly agreed. When they were asked aboutwhether an ordinary citizen should not participate in politics, a majority (56.5 percent) expressed disagreement. When we asked whether it was the responsibil-ity of the citizen to express his opinions on public affairs to the government, we recorded overwhelming support: 85 percent approved. It is clear that Macau citi-zens have a correct cognition of the values of political participation, in this re-spect differing sharply from traditional Chinese political culture. This progress in political participation is due partly to active promotion made by the government in this respect and the increased chances of participation over the years. Although colonial in nature, the Macau government, especially after the 1974 Portuguese revolution, has promoted political participation. Civic education has been added as a regular course in some primary and secondary schools. In past Legislative Assembly and City Council elections, the government has encouraged people to vote. Even the Chinese government supported the local elections.

Second, Macau is currently undergoing a transition from Portuguese rule to a post-1999 Special Administrative Region under Chinese sovereignty. The pace of change is picking up and a number of developments, such as the localisation of the civil service and the establishment of Chinese as an official language, have aroused public interest in government affairs. Throughout the years, the local Chinese appetite for and interest in participation have thus been expanded. Peo-ple have been drifting away from traditional Chinese ways and becoming more active in political participation.

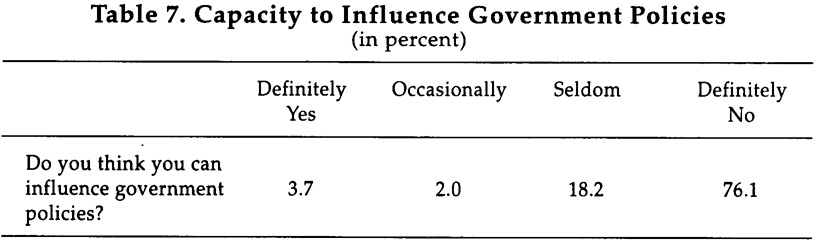

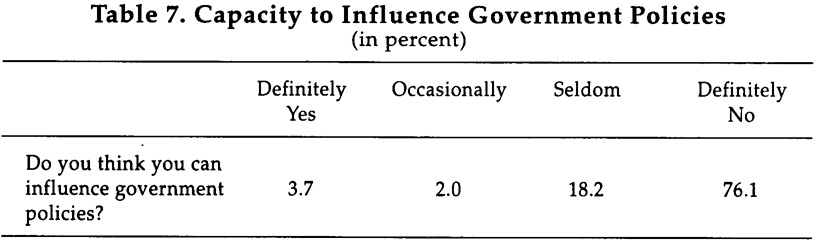

However, the general concurrence in obligations to participate in politics doesnot automatically translate itself into civic competence and real participation. Civic competence refers to the capacity with which citizens can influence the govern-ment's policy-making. The confidence one has over one's impact on government will boost one's interests and actual behaviour in participating in public affairs. In our survey, we asked a simple but very import-ant question: 'Do you think you can influence government policies?' (see Table 7). The answers indicate an ex-tremely low degree of confidence among the Macau Chinese in their capacity to influence government policies. Over three-quarters of our respondents believed that they absolutely did not have any influence on government policies. Only 3.7 percent believed they could influence government policies. This result contrasts sharply with the local people's general consensus on obligations to participate in politics. This general feeling of powerlessness clearly affects their actual political behaviour.

Over 90 percent of our respondents never tried to complain to government agencies or departments, ask the Legislative Assembly or City Council members for help, write to or telephone the press, radio or other mass media, participate in petitions, demonstrations, or sit-ins. Only 13 percent joined neighbourhood, or Kaifong associations, and only 6 percent the clan associations (Zongqin or Tongxianhui). Twenty per cent joined labour unions, business or professional as-sociations. Only 2 percent joined the political groups or people's livelihood asso-ciations. Our survey indicates that real participation in political and social activi-ties is extremely low in Macau. The activists are those of the locally-born elite who have received higher education.

Why did we record such a low degree of participation among the Macau Chi-nese? The traditional culture does not encourage the participation of ordinary people in government decision-making. The respect of people's wishes is impor-tant in Chinese tradition, but that respect depends entirely on the willingness of the top leader. If the top leader does not like this idea, the ordinary people can not force him. Within such a political framework, there is no room for ordinary people to care about and participate in public affairs. (Macau is similar to Hong Kong in this respect.5) Moreover, the colonial system in Macau has not encouraged public participation in the past. There has been a low degree of transparency, and limitedavailability of mass consultation in policy-making. Sometimes, popular complaints concerning irrational or wrong policies have received little or no response from the government. For example, the government continued for a long time to sell land by secret bidding, in spite of strong opposition and criticisms from the pub-lic and the media. Only recently has the present Portuguese administration changed this abnormal practice in land sales.

Conclusion

Macau is a small enclave with the highest population density in the world. Ninety-seven per cent of the population are Chinese who are strongly influenced by their traditional culture. They are also influenced by Western culture, repre-sented by Portugal. Against this background, a peculiar Macau political culture has emerged.

Using the Almond & Verba model, we have discovered the three main types of political culture (the parochial, the subject and the participant cultures) coexist in Macau. A small, well-educated elite participated in the political process as early as the 1970s. Since then many new issues have emerged, especially the localisa-tion of the civil servants, and the recognition of Chinese as official language. The local elite have also increased their activities and enthusiasm. They are given more opportunities to speak on the above issues, and they play an active role in the preparation and drafting of the Basic Law of the future Special Administrative Region of Macau. On the other hand, a large percentage of new immigrants to Macau are from the countryside in China. They have little education and live in the lowest social stratum. Their political culture is a mixed picture of parochial and subject political cultures. This is characterised by a certain degree of recogni-tion of the whole political system, and of the main government policies, such as economic policy, social welfare, safety and social security. They have a correct understanding of their rights and obligations as citizens and of the meaning of political participation. They know that a good citizen should vote, care about and take part in public affairs. However, their cognition of the whole system and the input objects are clearly much weaker than their cognition of the output objects. Last but not least, they have a low degree of confidence in their own political participation, believing that it will have little or no impact on government poli-cies. They have little interest in political actions. In summary, Macau people have a mixed political culture: the minorities have either a parochial or a participant political culture, while about half possess a subject political culture.

Notes

1 The survey results will be published in a Chinese book, co-authored by H.Yee, T.W.Ngo and Liu Bolong. This article analyzes a part of the survey data.

2 According to Almond and Verba's model, cognition refers to the knowledge of, and belief in the structure and functions of the political system; affection means a citizen's feelings about the political system, its role and government civil ser-vants; evaluation applies to people's judgement and opinions about the perform-ance of the political system and other political objects. See Gabriel A. Almond and Sidney Verba, The Civic Culture (Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press, 1963), p. 15.

3 Political objects contain various elements of a political system: general po-litical system, government structure, government policies and citizens themselves as important participants in a political entity.

4 In 1990, welfare expenditures accounted for 6 percent of total government expenditure. This figure is much lower than those of the Western powers.

5 A survey in Hong Kong indicated 88 percent of the respondents believed they could not change government policies. See Lau Siu Kai and Kuan Hsin Chi, The Ethos of the Hong Kong Chinese, (Hong Kong: Chinese University Press, 1987), pp. 94-95.