Gambling in Macau:A Macroeconomic Analysis

Kwong Che Leung Kwan Fung(China Economic Research CentreUniversity of Macau)

Gambling has long been the backbone of Macau's service sector. Together with the textile and garment industries, this sector constitutes a decisive portion of Macau's economy. This paper applies a macroeconomic analysis to investi-gate the significance of Macau's gambling in terms of its output share of Gross Domestic Product (GDP), its share of public finance and its linkage effects to other economic sectors. Results of the analysis reveal that gambling's share of GDP increased from 16.6 percent in 1982 to 23.5 percent in 1990. Gambling also carries substantial significance for public finance. Since 1988 more than 30 percent of government's public revenue and expenditure has been derived from gambling tax. These findings confirm the proposition that gambling tax plays an important role in financing Macau's public sector as well as its in-frastructure development. Further analysis of gambling's linkage effects to other related sectors shows that gambling generates demand in other linked sectors such as catering services, shopping spending, accommodation and transport, amounting to 12-15 percent of GDP. The linkage effect is clearly not to be overlooked. The analysis concludes with the possible fluctuation caused by the highly concentrated reliance of Macau's macroeconomy on gam-bling, the textile and garment industries.

Introduction

Gambling has long been the backbone of Macau's service sector through the concession granted by the Territory's government. Past research on Macau's gam-bling, such as Pinho1 and Kwan,2 are quite piecemeal and descriptive in nature. The purpose of this paper is to investigate gambling by applying a macroeconomic analysis. Macroeconomic analysis of gambling involves the studies of its output share of the national income, its share of public finance, and its linkage effect to other related industries. The paper is structured as follows: the concentration ra-tio is applied in the next section to measure the share of gambling in Macau's GDP. The following section explores the economic significance of gambling in public finance. Then the linkage effect of gambling is analysed. In the final sec-tion, conclusions are drawn from the preceding analysis.

Concentration Ratio: Share of Gambling in Gross Domestic Product

The concentration ratio is generally defined as "the percentage of total industry size accounted for by the few largest firms in the industry."3 It is com-monly applied to analyse the industrial structure by seeing whether a par-ticular industry is dominated by a few of the largest firms. However, by the same token, it can be further extended to examine the economic significance of the few industries by looking at the GDP share of those dominant indus-tries in the economy.4

Table 1 displays the concentration ratio of major industries, including tex-tiles and garments, tourism and gambling. Since 1982, the concentration ratio of the textile and garment industries has always been well above 30 percent (Table 1, Column 8), which is similar to that of tourism (Table 1, Column 9). Column 11 of Table 1 reveals the combined concentration ratio of textiles and garments and tourism. The ratio has been about 70 percent since 1982, which means that about 70 percent of Macau's GDP is derived from textiles, gar-ments and tourism.

Several conclusions can be drawn from this observation. First, the eco-nomic strength of Macau mainly rests on the textile and garment industries and tourism, as shown by the high concentration ratio. Second, as the ma-jor income earner of the Macau economy, a substantial share of the output value of tourism is constituted by gambling. Column 12 of Table 1 shows that gambling represents 45.0 percent and 63.4 percent of the output value of tourism in 1982 and 1990 respectively. Even if we look only at the con-centration ratio of gambling in Macau's economy, we observe a consider-able increase, from 16.6 percent in 1982 to 23.5 in 1990 (Table 1, Column 10). All these figures confirm the proposition that gambling shows an in-creasing economic share in tourism as well as in the macroeconomy. Third, a high concentration of gambling in Macau also implies that any turbulence in the gambling sector will mean corresponding fluctuation in the macroeconomy. This aspect will be dealt with in more depth in the analysis of the linkage effect of gambling.

Gambling and Public Finance

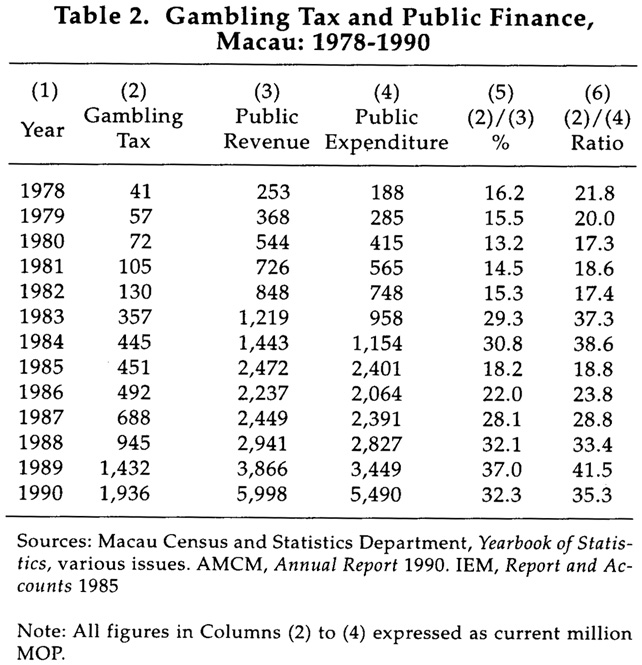

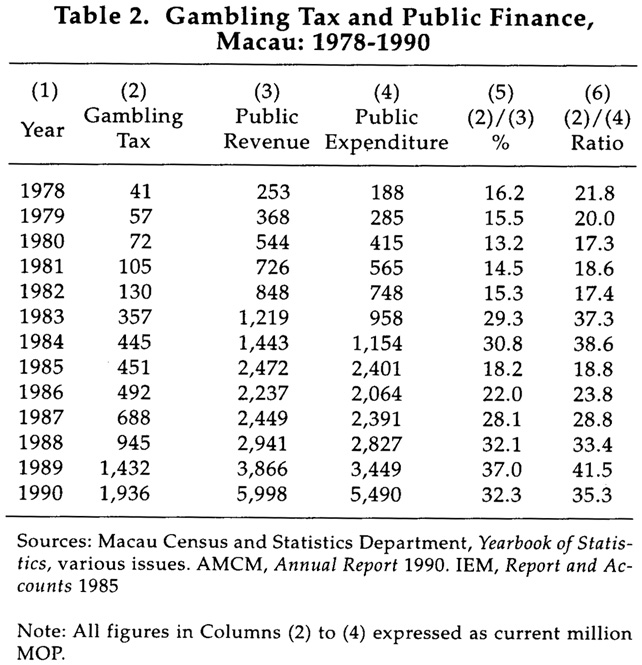

Apart from occupying a considerable share of GDP, gambling has great signifi-cance for Macau's public finance. Gambling tax soared from MOP41 million in 1978 to MOP1,936 million in 1990 (Table 2, Column 2). The average annual growth rate is 26.5 percent. The gambling tax as a percentage of the public revenue increased from 16 percent in 1978 to 32 in 1990 (Table 2, Column 5); while the ratio of gambling tax to public expenditure grew from 22 in 1978 to 35 in 1990 (Table 2, Column 6). The substantial contribution of the gambling tax to government revenue and expendi-

ture is undeniable. Of primary importance here is that the gambling tax not only finances the daily operation of the Government but also supports public works in Macau. These public works mainly include the construction of that basic infrastruc-ture necessary to maintain a smooth functioning of Macau's economy, such as the STDM'S responsibility for projects like the international airport, deep-water port, new Macau-Taipa bridge and reclamation and development in Praia Grande Bay. Viewed from this perspective, the gambling tax is vital both to Macau's public fi-nance and to its economic infrastructure.

ture is undeniable. Of primary importance here is that the gambling tax not only finances the daily operation of the Government but also supports public works in Macau. These public works mainly include the construction of that basic infrastruc-ture necessary to maintain a smooth functioning of Macau's economy, such as the STDM'S responsibility for projects like the international airport, deep-water port, new Macau-Taipa bridge and reclamation and development in Praia Grande Bay. Viewed from this perspective, the gambling tax is vital both to Macau's public fi-nance and to its economic infrastructure.

Linkage Effect of Gambling

In the preceding sections, the analysis has dealt with the share of gambling in terms of GDP and its role in public finance. However, gamblers' demands do not confine themselves to services provided by the casino. Gambling stimulates de-mand for other related economic sectors. In this section, we seek to investigate thelinkage effect of Macau's gambling, referring to the stimulus of inter-industry demand5 and more specifically to consumption linkage.6

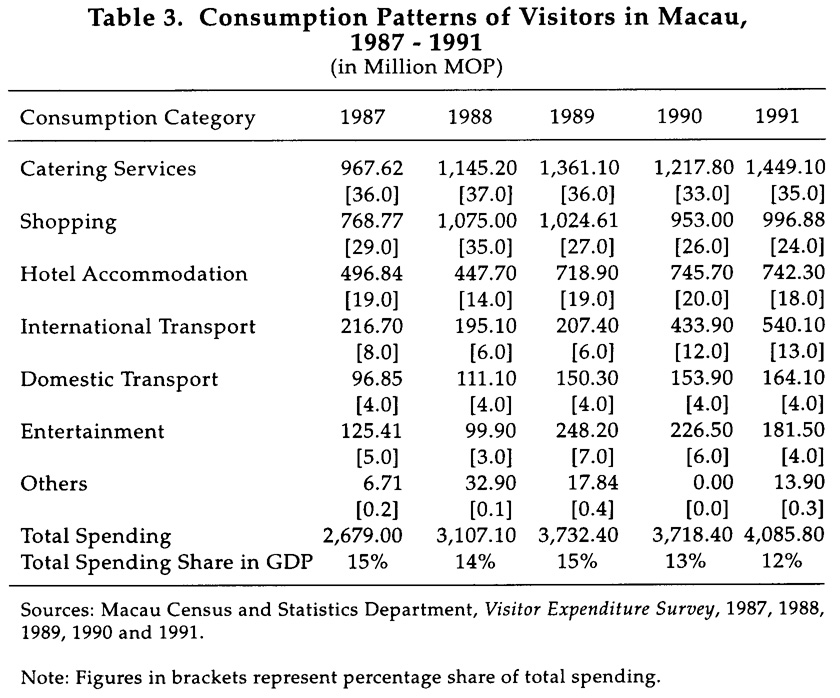

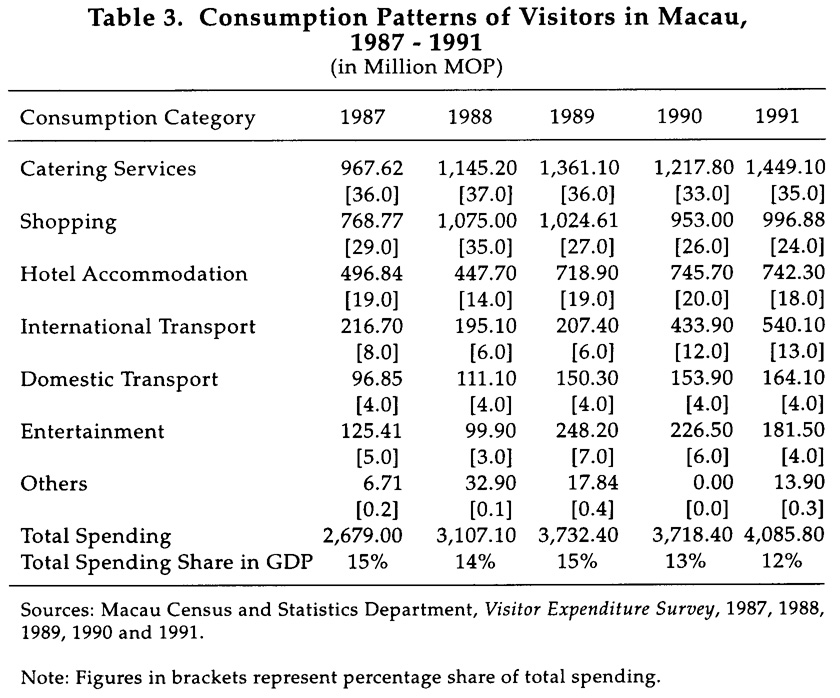

Table 3 depicts the consumption patterns of visitors to Macau by major con-sumption categories from 1987 to 1991. It shows that catering, shopping, hotel ac-commodation and international transport constitute the major components (more than 90 percent) of visitors' total spending. From a macroeconomic point of view, the output value of these consumption categories shares about 12-15 percent of Macau's GDP. This percentage can be regarded as the linked demand stimulated by gam-bling.

Further examination of Table 3 reveals that catering occupied the largest share, about one third, of total tourist spending from 1987 to 1991. Adding spending for shopping to catering raises the percentage share to 60. The share of accommodation ranged from 14 to 20 percent during this period; while the share of external transport exhibited a steady growth, from 8 to 13 percent in 1987 and 1991 respectively.

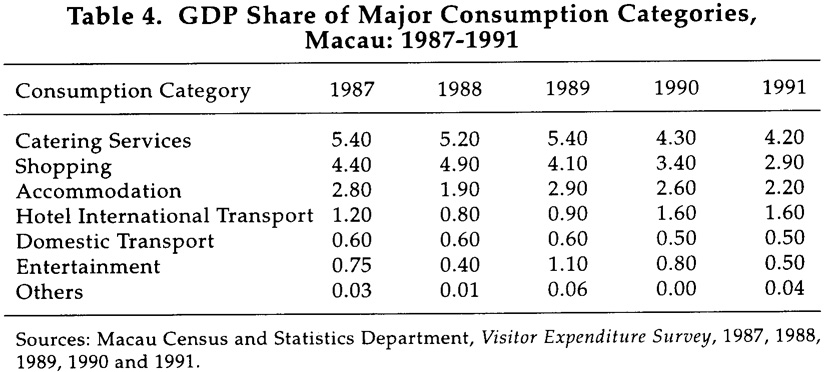

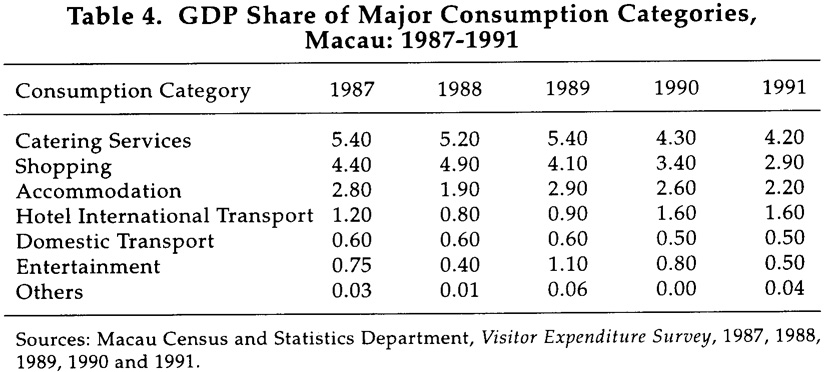

Table 4 expresses the GDP share of these consumption categories, which is a more relevant measure of their significance to the Macau's macroeconomy.

Again, the largest share falls to catering and shopping, 8 to 9 percent of GDP, while the average of accommodation and international transport is 2.5 and 1.2 percent respectively.

The economic implications of the above analysis are at least three-fold. First, gambling is important not only for its own sake but also for the linked demand it stimulates. As shown in Table 3, the output value of this linked demand forms 12 to 15 percent of Macau's GDP.

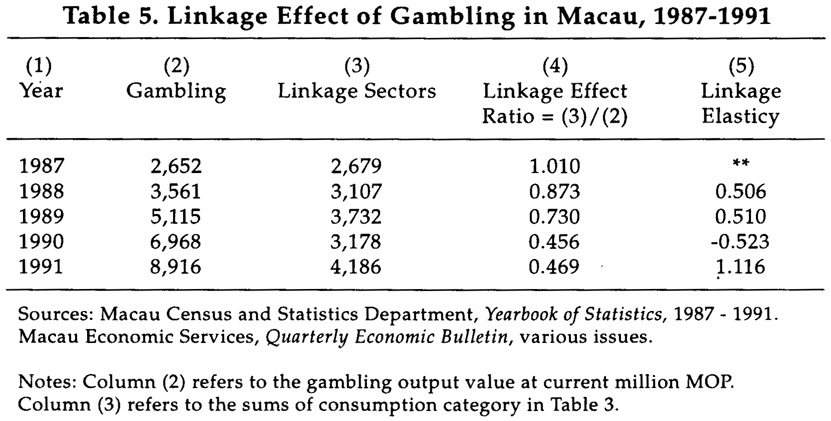

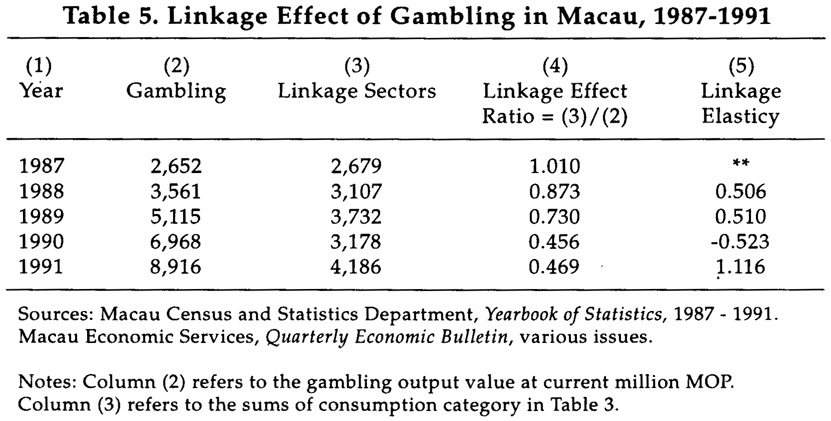

Second, if the first Observation is correct, it further implies that a fall in gam-bling demand will adversely affect these related sectors. To measure this effect we can establish the linkage effect ratio of gambling λ, such that: λ indicates the pro-portion of linkage sector outputs to the gambling output in a particular year. Ta-ble 5 shows λin selected years, e.g. one dollar output from gambling generated 73 cents output from the linkage sectors in 1989. Data reveal that λ declined from 1987 to 1991. Relatively speaking, the linkage effect for 1987 is much greater than for 1991.

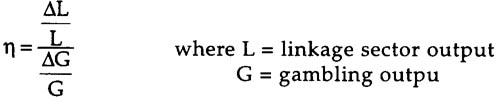

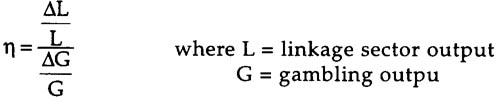

In further analysing the sensitivity of gambling output to other related sec-tors, the linkage elasticity η may be of help. This is defined as the percentage change of linkage sector output (ie, catering services, shopping, accommodation, interna-tional and domestic transport, entertainment, etc) relative to the percentage change of gambling output, mathematically,7

If 0 <η< 1, a 1 percent change in gambling output will lead to a less than 1 percent change in linkage sector output. If η > 1, a 1 percent change in gambling output will imply more than a 1 percent change in the linkage sector output. λ reflects the proportion of related industries' output generated by gambling out-put in a static concept while η considers such responsiveness from one year to the other, ie a dynamic analysis.

Data reveal that η was 0.506 in 1988 (Table 5, Column 5), implying an inelastic response of linkage sector output to gambling output (as a 1 percent increase in gam-bling output stimulated only a 0.5 percent increase in linkage sector output). A simi-lar case was found in 1989. In 1990, η was -0.523 while in 1991 it was 1.116 (elastic). This result shows that η fluctuated rather from 1987 to 1991. However, the repre-sentativeness of the result may be constrained by limited observations.

Third, this scenario is also applicable to the public finance aspect as gam-bling revenue directly determines the size of the gambling tax and government revenue, which in turn affect government spending and other public works.

Concluding Remarks

The preceding analysis confirms the common view that gambling is the main income earner of Macau's economy by establishing its share of GDP (the concentra-tion ratio in Table 1). This view is reinforced by the close relationship between gam-bling revenue and public finance, as well as by its linkage effects on other economic sectors such as catering, shopping, accommodation and transport.

However, as discussed in section 4, the linkage effects of gambling are sym-metrical. As gambling dominates a substantial share of Macau's economy, its ups and downs will directly affect the related sectors. This also reveals one major prob-lem for Macau's macroeconomy, which is the high concentration ratio (CR) of the few largest industries, namely the textile and garment industries, tourism and gambling. A high CR will mean a high degree of economic fluctuation, especially for exportables which are subject to exogeneous demand factors of the importing countries. As shown in Table 1, there has been a trend towards a declining CR in the textile and garment industries since 1986, while the CR of tourism has risen substantially. In addition, the gambling CR shows an upward movement far greater than the increase in that of tourism.

A suitable strategy to overcome this problem includes the diversification of Macau's economy by developing other potential sectors such as trade and finance. This can be made possible by perfecting the regulations concerning banking and finance, as well as by speeding the construction of software and hardware infra-structure. This direction of development should guarantee that Macau enters a stage of balanced growth with a lesser degree of potential fluctuation.

Notes

1 A. Pinho, "Gambling in Macau" in R. D. Cremer (ed.) Macau: City of Com-merce and Culture (Hong Kong: UEA Press, 1987), pp. 155-164.

2 Kwan Fung, "The Present and Prospect of Macau's Gambling" in H. Yee (ed.) Macau: Beyond 99 (Hong Kong: Wide Angle, 1993), pp. 213 - 228. (in Chinese)

3 D. W. Pearce, (ed.) The Dictionary of Modern Economics (London: Macmillan, 1986), p. 75.

4 E. K. Y. Chen, and K. W. Li, "Industry Development and Industrial Policy in Hong Kong" in E. K. Y. Chen, M. K., Nyaw, and T. Y. C. Wong (eds.) Industrial and Trade Development in Hong Kong (Hong Kong: Centre of Asian Studies, Univer-sity of Hong Kong, 1991), p. 4.

5 A. P. Thirlwall, Growth and Development with Special Reference to Developing Economies (London: Macmillan, 1989), p. 250.

6 J. Eatwell, M. Milgate,. and P. Newman (eds.) The New Palgrave: A Diction-ary of Economics, vol. 3 (London: Macmillian, 1987), pp. 208-209.

7 Here we refer to the concept of arc elasticity and the computation that is based on the data from Table 1 and Table 3.

ture is undeniable. Of primary importance here is that the gambling tax not only finances the daily operation of the Government but also supports public works in Macau. These public works mainly include the construction of that basic infrastruc-ture necessary to maintain a smooth functioning of Macau's economy, such as the STDM'S responsibility for projects like the international airport, deep-water port, new Macau-Taipa bridge and reclamation and development in Praia Grande Bay. Viewed from this perspective, the gambling tax is vital both to Macau's public fi-nance and to its economic infrastructure.

ture is undeniable. Of primary importance here is that the gambling tax not only finances the daily operation of the Government but also supports public works in Macau. These public works mainly include the construction of that basic infrastruc-ture necessary to maintain a smooth functioning of Macau's economy, such as the STDM'S responsibility for projects like the international airport, deep-water port, new Macau-Taipa bridge and reclamation and development in Praia Grande Bay. Viewed from this perspective, the gambling tax is vital both to Macau's public fi-nance and to its economic infrastructure.