Planing for High Concentration Development:Reclamation Areas in Macau

Bruce Taylor(Faculty of Social Sciences and Humanities University of Macau)

This paper discusses the principles that underlie the planning for Macau's two newest areas of land reclamation: the so-called "NAPE" reclamation in the Outer Harbor area and the Praia Grande or Nam Van project adjacent to the commercial heart of the city. The plans developed for these two projects are contrasted with that drawn up for an earlier area of reclamation designated for multi-purpose land use, the Outer Harbor or "ZAPE" area. It is suggested that lessons learned from the chequered history of the ZAPE plan's implemen-tation have been incorporated into the NAPE and Nam Van plans -- at the risk, however, of creating an overly-rigid framework governing development in these areas with no flexibility for accommodating, say, economic changes affecting levels of risk and reward in the market for property. The paper also speculates on the impacts of these large new developments on the character of the broader urban environment and on the quality of urban life experienced in Macau.

Introduction

One editor of a book describing Macau's urban development has recounted his difficulties in finding any author willing to discuss planning in Macau -- pre-sumably because of an unwillingness to raise a subject where many are prone to find fault.1 Certainly Macau has its share of urban problems, some of which in other cities are addressed with varying degrees of success by urban planners: traf-fic congestion, lack of sufficient open space, and environmental deterioration are only three that could be cited from a long list. Yet it is not accurate to say that Macau's growth has been unplanned. At various times in Macau's history for-ward thinking -- for that is all that "planning" is, in the end -- has gone into the choice of suitable locations for many of the elements taken for granted in today's city, ranging from fortresses to major roadways and even to whole districts, such as the São Lázaro area (fortunately preserved). And the present development pro-gram of the Macau Government focusing on major infrastructure works, such as the International Airport, can only be carried out with reference to some over-arching vision of future patterns of physical growth and change that are desirablefor Macau -- whether or not this vision is translated into a "comprehensive plan" in the Western tradition.

Some of the best examples in Macau of planned new developments are the various areas of reclaimed land. The reclamation of land from the sea has been a continuous process throughout Macau's history.2 Older reclamations, such as the Praia Grande scheme of the 1920s that created the heart of today's central busi-ness district, are mostly of historic interest. Newer reclamations, on the other hand, provide an excellent opportunity to observe and assess the extent that forward thinking -- or planning, if you like -- has been able to at least assist in producing improvements in living conditions and a better overall quality of life in Macau, taking into account the economic, political, and other contexts that affect all local development.

This paper examines the planning and design principles that are embodied in the published plans for Macau's newest areas of multi-purpose land reclamation:the extended Outer Harbor reclamation, known as NAPE after its Portuguese name Novo Aterro do Porto Exterior, and the Praia Grande or Nam Van development now emerging from the former Baia da Praia Grande, at the heart of the old city. The planning controls adopted for these two developments are contrasted with those applied to the slightly older Outer Harbor area (or ZAPE), extending from the Hotel Lisboa to the new ferry terminal and adjoining reservoir. After first discuss-ing the implementation of the ZAPE plan and the nature of the controls applied in the two new development areas, I evaluate whether the new and different system for regulating building that is employed in NAPE and Nam Van is likely to pro-duce outcomes that are significantly more favorable in terms of the character of the urban environment that results, and I speculate further on the implications of these large new developments for the overall quality of urban life experienced in Macau.

The ZAPE Reclamation

According to the chronology contained in Prescott's recent volume, the recla-mation of the area known formally as Zona Aterro do Porto Exterior, or ZAPE (and informally as simply Porto Exterior or the Outer Harbor) occurred in the 1920s.3 The area was serving as a point of arrival for visitors to Macau as early as the late 1930s, when Pan American World Airways "flying boats" called at a maritime ter-minal located near to the present Mandarin Oriental hotel. But as late as the mid-1970s the predominant land use in the area was agricultural.4Even the relocation of the ferry services from Hong Kong to a terminal situated in the Outer Harbor in the 1950s, and the incorporation of the waterfront road into the Macau Grand Prix circuit, did little to change the undeveloped character of the area.

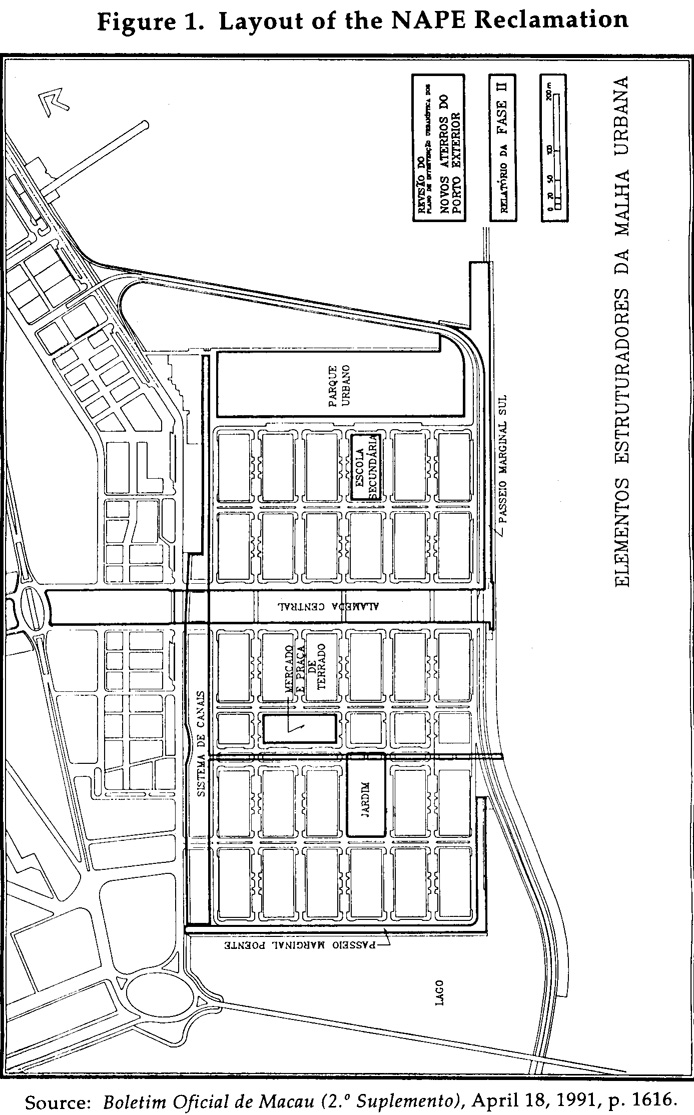

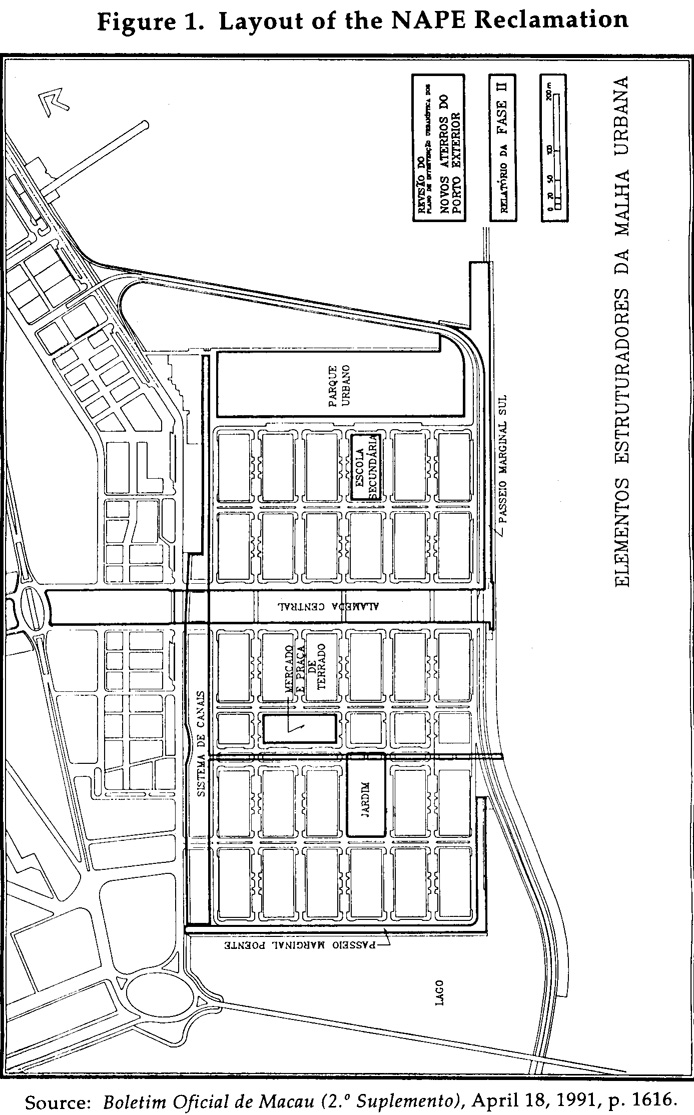

It was not until 1978-79 that an overall plan for development of the ZAPE area was drawn up, under the supervision of the local architects Eduardo Lima Soares and Jon Prescott.5 This plan incorporated a number of the important fea-tures that are evident in the area today, including the central park (alameda) andthe tunnel under Guia Hill linking the district with the densely-populated central areas of the Macau peninsula. (Interestingly, neither of these important public amenities was completed until the early 1990s, long after many private buildings had gone up in the Outer Harbor). The plan also showed a proposed street layout (partially shown in Figure 1); divided the land into blocks that could be léased to developers; set aside sites for public facilities, such as the arena now known as the Macau Forum; and contained provisions to regulate the height and density of build-ing construction in the district. The drafters of the plan envisaged that most build-ings would be mixed commercial/residential structures, fundamentally the same in concept (though different in scale) as the traditional shophouses that still line Avenida Almeida Ribeiro, with commercial space in street level podiums shel-tered by covered pedestrian arcades, and residential units located in towers above.

Almost immediately after the appearance of the plan changes occurred in the nature of land use in the area. By 1983 most of the earlier agricultural plots had disappeared; Edmonds' map of that year shows most of the Outer Harbor as "un-occupied" (perhaps more accurately described as "awaiting construction").6 But the pace of building in the area has been sporadic. A few waterfront buildings (most notably the Presidente and Excelsior [now Mandarin Oriental] Hotels) were completed before 1985, but the bulk of residential building including the giant Centro Internacional de Macau has occurred in the last five years. At the time of writing (early 1994) several building projects are in progress, at least two of them restarted after lengthy periods of abandonment, while other parcels of land still await attention. The road network servicing the area is at last approaching its full development, with the recent commencement of construction on a grade-separat-ed underpass on Avenida do Dr. Rodrigo Rodrigues.

Thus the period between conceptualization and full implementation of the ZAPE plan has already spanned fifteen years, with the end not yet in sight. It is not surprising, given this time lag and the rapidity of change in Macau, that the Outer Harbor area as built today differs in many respects from the district that was planned fifteen years ago. What is more surprising is that many design pro-fessionals view these changes as almost uniformly for the worse: Prescott, one of the original planners, has called the area "visually the biggest disaster in Macau,"7 and others have lamented the missed opportunity to create a showpiece develop-ment as opposed to an assemblage of tall buildings. What could have gone wrong during the plan's implementation that would justify so harsh a verdict regarding its outcome? Three principal difficulties suggest themselves, although these cer-tainly do not exhaust the list of problems that had an effect on ZAPE.

1. Changes in concept. Over time a number of conceptual changes have been made in the development pattern proposed for ZAPE. Some of these are due to actions taken by government regulators; for instance, the early idea of allowing the tallest buildings to be along the waterfront was modified when concerns were raised in official circles about maintaining an unobstructed view of Guia Lighthouse (with the result that taller buildings, with a couple of notable exceptions, are now grouped towards the Hotel Lisboa end of the reclamation). Likewise the central alameda now cuts completely across the internal street pattern, disrupting the continuity of pe-destrian circulation which was the planners' original intention.

Other, and probably more significant, changes have been the result of build-ers' responses to their perceptions of the market for both commercial and residen-tial space in the Outer Harbor. The loca-tion of commercial units (shopfronts) has seen the most radical change. Originally the focus of commercial activities was to be along pedestrian shopping streets extending virtually the length of the district. Some of these narrow, arcaded passageways have actually been built (although not exactly to the original design); however, few of them have attracted many shops. Businesses have instead been lured to more visible shops that front on the area's major streets (and thus are more obvious to, say, passing bus travelers). Indeed, a sort of vicious circle has developed in which builders, seeing that shop-fronts along the pedestrian alleys do not attract tenants, refuse to provide them at all in their newer buildings -- which in turn makes the alleys even less attractive. The outcome is a wholly undesirable situation where the alleys are bleak and empty, while the streets of the area are lined with parked (sometimes double-parked) vehicles, reducing their effectiveness as carriers of through traffic.

There are still other conceptual changes for which no party can be blamed; over time, they "just happened." An example is the gradual shift in the focus of development from Avenida do Dr. Rodrigo Rodrigues, the interior road at the foot of the Guia ridge and the original "main street" of the area, to the waterfront Avenida da Amizade. The writer's view is that this was a natural outcome of the move-ment of people and traffic in the area: the waterfront road offered (and still offers) the most direct route between the ferry terminal and the Hotel Lisboa, the two main generators of traffic in the Outer Harbor. In addition, it was the waterfront sites that were most attractive to developers who built early on the ZAPE recla-mation, having not only the highest visibility to traffic but the most pleasant views as well.

2. Inconsistent enforcement. Like other development plans of the period, the plan for ZAPE had no formal legal status in that it was not "gazetted" in the Gov-ernment of Macau's Boletim Oficial. As a consequence, officials responsible for is-suing permissions for new building projects were not legally bound to follow any of the guidelines set forth as part of the plan. Persistent, influential, or simply fortunate developers have received approval for buildings that contravene estab-lished height restrictions; that fail to include commercial spaces along the pedes-trian alleyways; that incorporate vestigial arcades, purely decorative rather than functional in character (and of very little use as shelter in a rainstorm!); or that deviate from the "norms" envisaged by the planners (who in this case had no real control over implementation) in other ways.

When coupled with the conceptual changes noted earlier, the outcome of this inconsistent enforcement of planning and design guidelines is to reinforce the perception of the area as an assemblage of unrelated structures thrown together onto adjacent building lots; a hodgepodge of buildings rather than a coherently planned, truly designed environment for higher-class residences, shopping, rec-reational activities, and tourism. This might be expected in an area that is still in the course of development, with numerous empty lots interspersed with construc-tion sites and completed buildings. But the feeling of "unrelatedness" remains even in those parts of ZAPE that are largely complete. The presence of buildingsthat stand out disconcertingly from their neighbors is in part a legacy of inconsist-ent enforcement of those guidelines that have been in place at different times of ZAPE's development (as well as the proclivities of individual designers and their clients, discussed next).8

3) Visual disorder. The hodgepodge appearance of building in the area is re-inforced by the diversity of architectural expression that is apparent. This is noth-ing new to Macau; the shopfronts along Avenida Almeida Ribeiro are equally di-verse in detail, but still retain a sense of harmony owing to their fundamental similarity in height, bulk, intended use, materials and finishes used, and cultural influences affecting their design.9 At the much larger scale adopted for structures built in ZAPE, however, any underlying sense of unity is lost, while diversity comes to the fore: diversity in materials, in colors, in the treatment of architectural ele-ments such as windows and arcades, and in the cultural references incorporated into the designs. Some of the structures erected on different building lots in the ZAPE reclamation seem to be vying with each other to attract the attention of viewers. This is particularly true of the hotels sheathed largely in glass, although other commercial/residential buildings also call attention to themselves owing to, say, the distinctive design of their street-front arcades.

In some ways visual disorder cannot be termed a failure in planning; the lack of consistency in design evident in modern buildings in Macau reflects the diffi-culties inherent here, as elsewhere, in conceptualizing a "modern vernacular" equivalent to Macau's traditional hybrid Chinese/Portuguese architecture but adapted to use with the building types in demand today. When this lack of con-sistency is combined with the failures of implementation noted earlier, though, it accentuates the problems associated with them and further contributes to the sense that the district was not planned, but simply "appeared," with little benefit from official oversight or guidance. This is the unfortunate impression that is left with many people who view the ZAPE development.

The NAPE and Nam Van Reclamations

Physically the NAPE reclamation is an extension of the earlier ZAPE reclama-tion (see Figure 1), carried further out into the sea. The first proposals for this reclamation were developed in 1982-83, as part of a consultancy study aimed at defining new sites for the expansion of the main urban area. Physical reclamation of the land started in 1988 and the final plan for the area was adopted officially in 1991.10 Unlike the plans for the ZAPE reclamation, the plan for NAPE has been "gazetted" or officially recorded in the Boletim Oficial. As such, it has the force of law behind it, and officials from the Public Works Department (Obras Públicas) and other government departments are bound to enforce the regulations that form part of the officially-gazetted plan.

These regulations are very stringent, again in sharp contrast with those im-posed on the ZAPE reclamation. Height limits are strictly enforced: 80 meters for some sites (office and hotel buildings), 50 meters for others (residential buildings).There is no doubt that builders will choose to develop the sites to the maximum permitted extent: thus eventually the profile afforded by structures built on the reclamation should be largely flat, similar perhaps to that seen in the Kowloon Peninsula in Hong Kong until very recent times. Building types can vary only marginally between one site and the next. The dominant style of building is the "podium and tower" residential/commercial structure adopted in ZAPE and throughout the newer sections of Macau. Commercial uses are accommodated on the lower floors of these buildings, which are built to the edges of the property line. At the street level, the buildings must be provided with arcades, the dimen-sions of which are also specified. Residential flats are built above the podium lev-el, in a rough "U" shape that leaves space for an interior courtyard. For each site, the gross permitted floor area is specified to the precise square meter; one hotel site facing ZAPE, for instance, has a permitted floor area of 43,102 square meters, of which 37,878 are to be on floors used for hotel purposes. Such rigidity of con-trol is typical of building sites on the NAPE reclamation.

The plan itself provides a street layout in the shape of a regular grid, with the north-south streets spaced twice as far apart as the east-west streets (Figure 1). The central alameda is a continuation of the one implemented in ZAPE. For drain-age purposes (and perhaps to provide a physical and conceptual separation from the more disorderly ZAPE district?), a canal runs along the edge of the district closest to ZAPE. Sites are provided for a large urban park along the eastern edge, for a secondary school, for a market and commercial center, and for one other small park. A bypass highway will extend along the seaside, with a pedestrian promenade along much of the water's edge.

As in ZAPE, rights to build on the building sites provided on the NAPE recla-mation have been leased to private developers, in most cases for substantial pre-miums running into the hundreds of millions of patacas. Each site will be devel-oped separately by the builder holding the development rights; the first buildings are likely to open in late 1994.

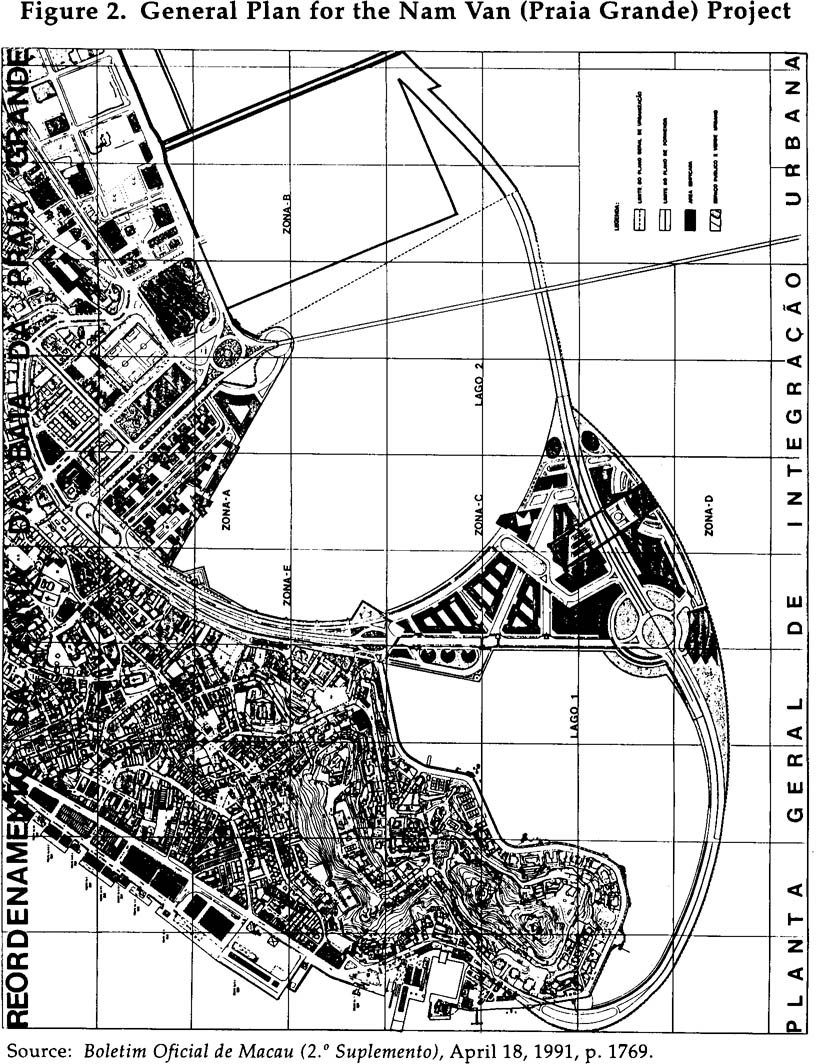

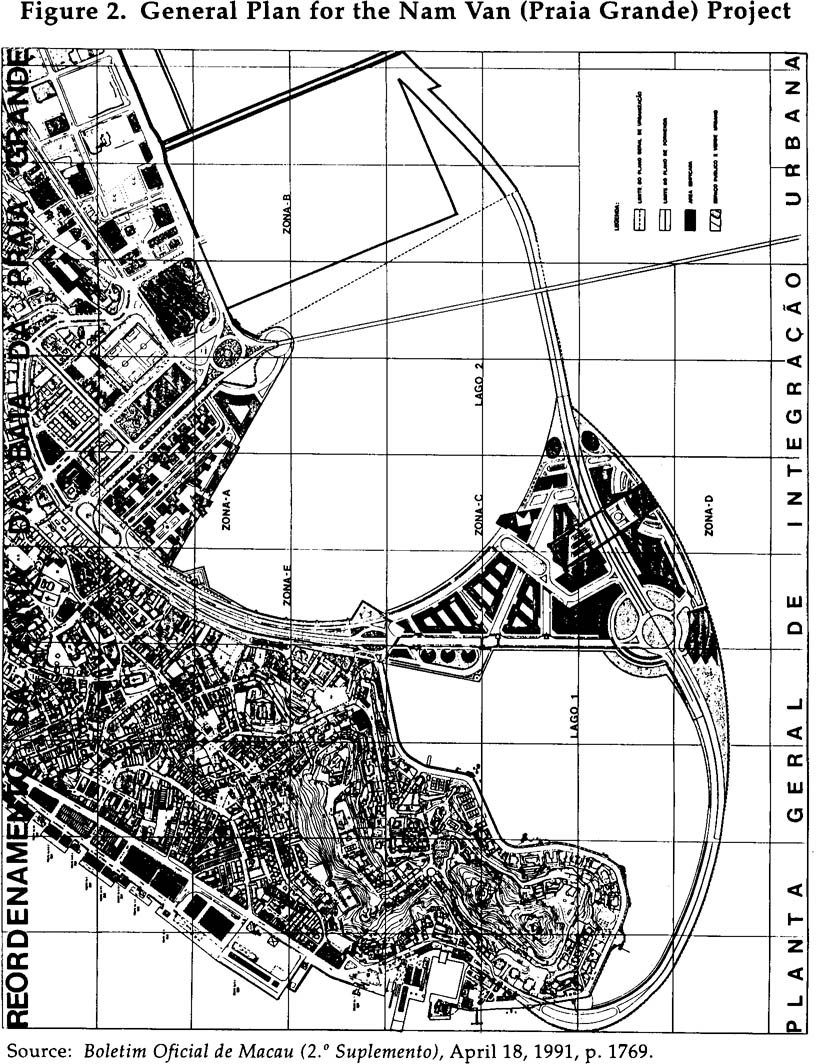

The newest of the major multi-use reclamation projects that are so transform-ing Macau is the Nam Van or Praia Grande development, the plan for which is shown in Figure 2.11 This plan represents nothing less than a fundamental re-structuring of the historical pattern of urban development in the heart of the city. As such, it is a much more ambitious (and expensive) project than the NAPE reclama-tion; one estimate of the total project cost is MOP 11 billion (or US$ 1.4 billion), which is some 50 percent higher than the cost of Macau's International Airport (MOP 7.3 billion).

The plan for the Nam Vam development, developed by local architect Manuel Vicente, centers around two fresh-water lakes that will be created through enclo-sure of the Baia da Praia Grande. In between these lakes will be an island, roughly triangular in shape, which will house the largest quantity of new development. Two other major building sites are provided for in the project plan. Zone A repre-sents an extension of the existing central business district, extending along Aven-ida do Doutor Mario Soares from near the Lisboa Hotel to the Rua da Praia Grande itself. Zone B represents an extension of the NAPE reclamation, and has been planned so as to be in harmony with that reclamation.

A distinctive feature of the Nam Van reclamation is that the entire project is the responsibility of one company, the Nam Van Development Company, which will develop the zones in three phases. Thirty-one sites are earmarked for private development, either by the Nam Vam Development Company or by joint venture enterprises. Fifteen other sites will be used by the Macau Government for various public uses, including government offices and cultural/recreational facilities. Pub-licity issued by the Nam Van Development Company suggests that some 16 mil-lion square feet of space will be built, not counting 3 million square feet of sorely-needed underground car parking.12

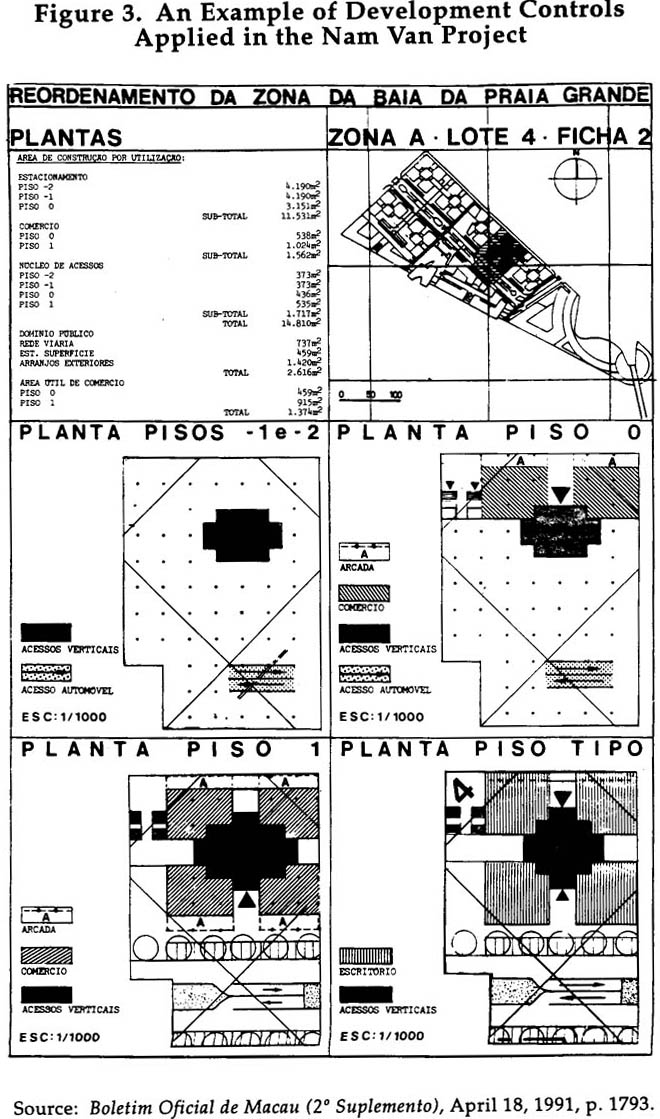

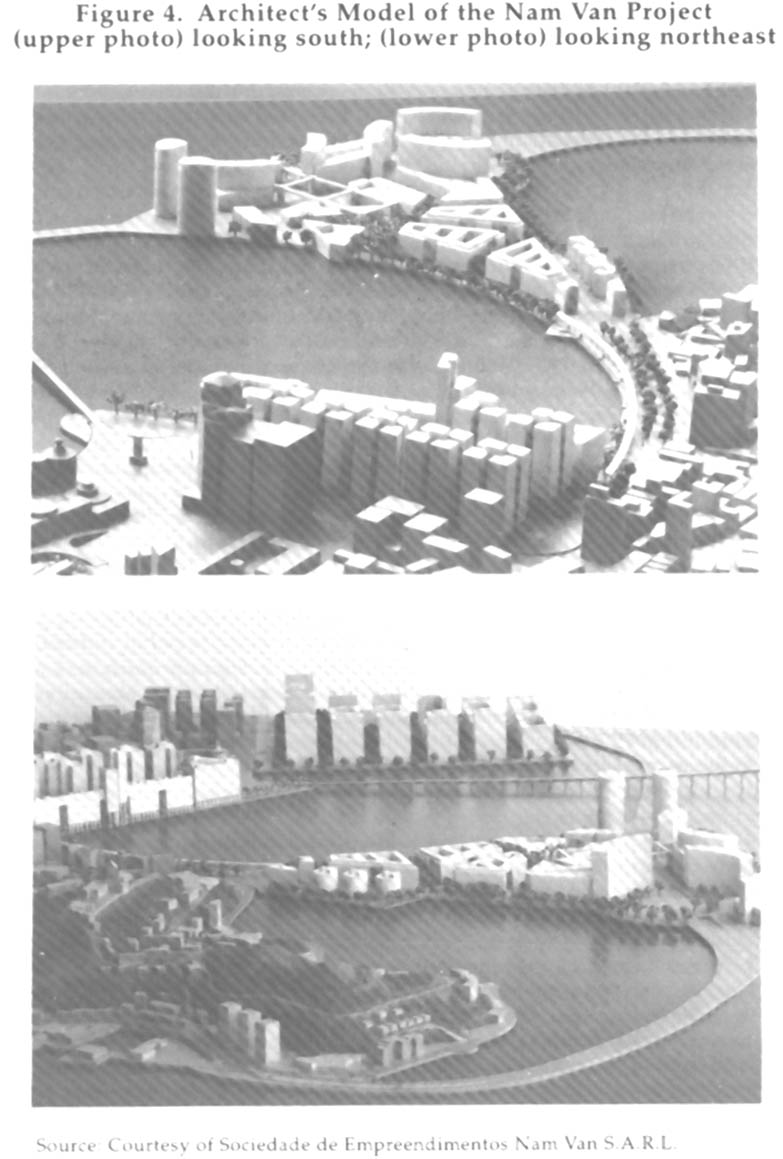

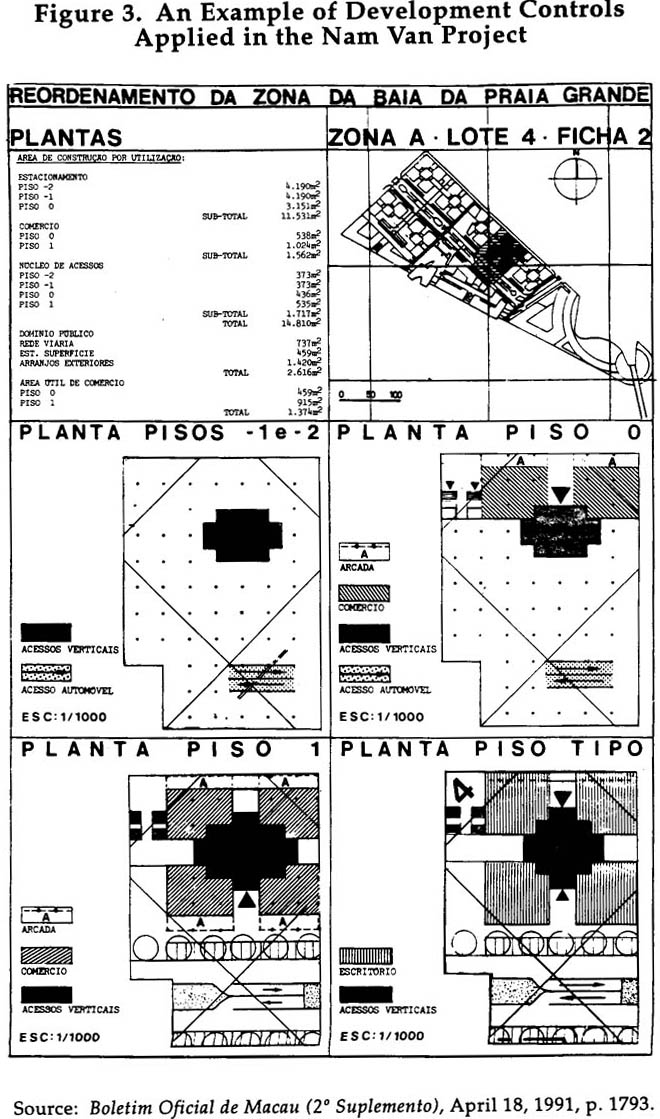

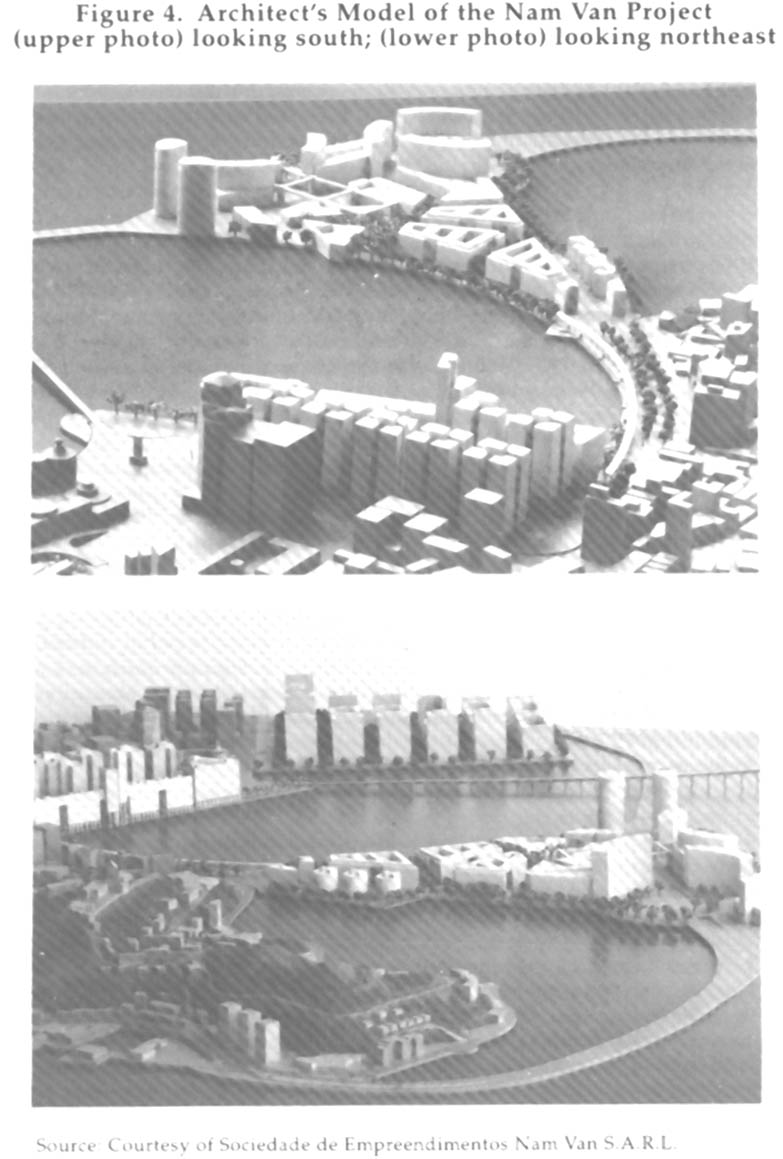

Like the NAPE reclamation, the Nam Vam project incorporates strict plan-ning control over the character of development permitted on each building site. Figure 3, reproduced from the Boletim Oficial, gives an illustration of the rigidity of these controls as applied to a site in Zone A of the plan. The building on this site is to be an office building, with some commercial space at the lowest levels. The area occupied by each floor is carefully specified; so is the area of commercial space and, unusually, the area to be occupied by elevators and stairways provid-ing access to the upper floors. Three floors of underground car parking are also provided. Heights are of course strictly controlled, both in terms of overall height and height per floor. The dimensions of external arcades fronting on the main streets are specified, as in NAPE. Even the type of external finish (typically mosaic tile) is prescribed. It is evident that the architects who design structures on the Nam Vam reclamation will have strictly limited scope for individual expression, and no scope at all to alter building volumes, shapes, or even colors. As a result, the computer-generated rendering of the finished project reproduced here as Figure 4 will ap-proximate very closely the appearance of the actual development. This again is in marked contrast to ZAPE, where significant changes have taken place over the fifteen years of the area's development.

Discussion

From the previous discussion, it is evident that a dramatic philosophical shift has taken place in Macau with regard to the regulation of new building activity. From a mostly laissez-faire, informally administered regulatory framework oper-ating within broadly-conceived guidelines, exemplified by ZAPE, the pendulum has shifted in the opposite direction to very tightly-controlled, legally enforcea-ble, and minutely detailed sets of regulations, such as those applied to both the NAPE and Nam Van projects.

At first glance, this would seem to be a most desirable state of affairs, since it means that the worst of the problems that have arisen in ZAPE over the course of its development simply cannot happen again. Changes in the conceptual basis of the plans for NAPE and Nam Van are most unlikely now that the two plans are gazetted and have the force of law. Inconsistent enforcement is eliminated by hav-ing detailed specifications for the buildings located on each site incorporated into the plan. Any modifications to these cannot be made, as sometimes in the past, byan individual official, but must be made via a "Portaria" or decree issued by the Governor of Macau. Visual disorder is regulated by controlling building volumes, shapes, and finishes, as well as the character of certain architectural elements such as street-front arcades. Instead of being a hodgepodge, the new developments must, of necessity, exhibit visual harmony -- though created here merely by conformity to the regulations rather than (as in earlier times) stemming from any underlying similarity in vision on the part of builders and developers.

Yet there is also another, more problematic side to the new orthodoxy im-posed by the building regulations applied to NAPE and the Nam Van project. One potential difficulty is architectural; it arises because of the enforced degree of vis-ual coherence that is created by the rigid building regulations applied to each site. Faced with serious constraints on their ability to design creatively, it would not be surprising to see some architects taking the "path of least resistance" and design-ing minimalist buildings, with little ornamentation or other distinctive features, simply fulfilling the stated requirements and not at all special in any way.13 The orthodoxy that results may be harmonious, in a broad sense, but it is likely to be quite bland at the same time; impressive in scale but with very little to delight the eye. This would be a most unfortunate outcome for the Nam Van project in partic-ular, which is intended to be a showpiece illustrating Macau's development po-tential into the next century.

More serious problems are created by the inflexibility that is built into both the NAPE and Nam Van development plans. End users who seek to rent or pur-chase offices, flats, or commercial space in new buildings constructed on these reclamations will find their choice restricted. In Zone A of the Nam Van project, for instance, eight sites are to be developed as office buildings, all looking very similar (Figure 3 is an example). It would not be surprising to see all eight of these buildings not only looking very much alike but also being very much the same in terms of the type of office space available -- as measured by floor area, quality of fittings and fixtures, amenities available (e.g., presence or absence of "intelligent" building systems), and (not least!) purchase prices or rent levels. This is partly due to the natural tendency of developers to construct buildings that are not no-ticeably different -- e.g., plainer or fancier in appearance -- than others in the same general vicinity.

The problem arises because end users themselves fit no convenient profile, and the needs of end users vary over time. As Prescott puts it,

One wonders how the requirements of the individual enterprises which will occupy these buildings will be restricted by the strait-jacket of precise, very detailed layouts.14

A small business -- say, in a professional field such as accounting -- may require at first only a small suite of offices, to house one or two associates, a secre-tary, and limited storage space for files and other records, together with basic fa-cilities like a fax machine. A larger firm in the same field may have ten or more associates, several clerical staff, voluminous records, and international connec-tions requiring high-speed networked computers -- to say nothing of the intangi-ble "prestige" factor that translates into a perceived need for offices with a central location, or with a certain quality of finish (wood paneling, marble lobbies, and the like). At any one time there are a broad spectrum of office users, with very different needs that are best served by office buildings of very different character. But this is precisely what will not be available in either the NAPE or Nam Van developments, where inevitably the office buildings will end up being more alike than different. Flat buyers and retail shop owners will be faced with much the same limitation in choice.

The result may be that as new buildings in both NAPE and Nam Van come on line, there will be oversupply in the particular market niche served by the bulk of the new construction. This may lead to cutthroat competition among building owners for office or commercial tenants (particularly in NAPE where each build-ing is independently developed); for residential buildings, it may depress flat prices or simply mean that sales take much longer than first envisioned.15 Meanwhile there remain numerous other markets (less well-off families, for one) that are left unserved. Surely it might have been possible to incorporate a wider range of building designs into both the NAPE and Nam Van development plans, allowing for a broader spectrum of end users to be served while not detracting in the end from the sought-after visual harmony that seems to have been the designers' main concern.

These concerns are exacerbated by boom-and-bust conditions affecting Macau's overall property market. In the past Macau has experienced a number of boom-and-bust cycles: for instance, a boom in the late 1970s and early 1980s was responsible for transforming the appearance of a number of the older parts of Macau (and for a good deal of demolition of historic property). Inevitably there will be property developers who predict these cycles inaccurately and face finan-cial disaster; perhaps they have built hotels at a time when the territory has a glut of hotel rooms (as in 1993). Under a flexible regulatory regime, there are several "safety valves" available for these developers. Perhaps they may petition the Gov-ernment to allow a change in land use: from a hotel building to, say, office space. Perhaps they may modify the design of the building even while it is under con-struction: for instance, subdividing larger flats into smaller ones, or converting a five-star hotel to a less expensive property. A builder may even stop work alto-gether on a project, either to allow for a more propitious entry into the market or to await regulatory approval of a desired change. It is not unheard of for a devel-oper in Macau to "sit on" a partially completed or even a wholly completed project for years until approvals are obtained for a change of use or design.16

These "safety valves" will not be available -- or at least not as readily availa-ble -- in the NAPE and Nam Van developments. Changes of use and changes of design are precluded by the strict planning controls that have been gazetted into law. And although there may be some flexibility in the timing of development, the Nam Van Development Company in particular is virtually locked in to its an-nounced schedule for completing the project in the symbolically important year of 1999. There is no question that property developers participating in these projects under the very rigid restrictions imposed by the two development plans may be in a position to benefit handsomely from what one writer has called Macau's "big-gest gamble" -- to create the physical infrastructure needed for a modern centerof trade, industry, and cultural interchange that will retain its significance beyond the 1999 handover to Chinese administration.17 But they are participating on terms that are much less favorable, and ones that incorporate higher degrees of risk, than those available to their predecessors who participated in the development of ZAPE, or of other parts of the city.

One final area of concern is the impersonal and dehumanizing scale adopted in both new development projects (and in ZAPE as well). Despite rampant de-struction of the historic townscape, large parts of Macau (including, notably, the Praia Grande and especially its southern extension, Avenida da República) are still blessed with a sense of human scale in which the observer blends comforta-bly into his/her surroundings rather than feeling overwhelmed by them.18 The megastructures planned for NAPE and, especially, for the Nam Van development -- such as the solid wall of "prestige" residential buildings planned for Zone A, fronting on the artificial lake -- represent perhaps the antithesis of human scale, and sit most uneasily with, say, the tree-lined Praia Grande enjoyed by so many residents and visitors today. The sense has been given that in the rush to create the appearance of modernity and progress, the needs of the people who actually use and experience these new developments have been overlooked.19 And there is no question that the visual prominence of these new developments will lead to sharply changed public perceptions of the character of urban Macau: "shiny and new" per-haps, but also hard-edged, monumental, mechanistic and, ultimately, oppressive in nature rather than humanistic, accessible, and fundamentally satisfying.

Conclusion

In the last analysis, the forward thinking associated with plan-making should be directed for the benefit of people. Physical planners who purport to serve the public interest should, by their plan-making and regulatory activity, act to direct the evolution of an area's built form so as to improve living conditions and en-hance overall quality of life. Attainment of this objective is necessarily in doubt when the implementation of a plan is so loosely guided and monitored that, in effect, almost anything goes -- as many believe has been true for the ZAPE recla-mation. But, equally, this objective is hard to attain if the basic principles that guide planners in their work are not user-centered but, instead, are abstract ideas of order and conformity, enforced by development restrictions specified in precise detail. Perhaps in response to the excesses evident in ZAPE, the planners respon-sible for the development guidelines applied to the NAPE and Nam Van districts have overreached themselves in stressing a rigid, formulaic approach to urban design that in the end can only be described as soulless, with the individual occu-pant or user (or even property developer) becoming, in essence, little more than a cog in a machine.

I must express my serious doubts as to whether the trend towards a more formalized mode of plan-making, as is evident in the planning for the NAPE and Nam Vam development projects, will lead to much improvement in the living con-ditions and overall quality of life experienced by residents of Macau. And while I would not wish to see the experiences of ZAPE repeated, I do believe there is room for a middle ground: a plan-making process that is both firmly directed in terms of the fundamental objectives to be attained, and flexible in terms of the details of implementation. Perhaps one of the best legacies that Macau's present government could leave to its post-1999 successor is the institutionalization of such a process, whereby Macau's physical development is guided in ways that act to enhance the quality of urban life.

Notes

1 Jon Prescott, Macaensis Momentum (Macau: Hewell Publications, 1993). The discussion referred to is on p. 51.

2 For illustrations of this, see Manuel Alves, "O Espaço Territorial de Macau," in D.Y. Yuan et al., eds., Population and City Growth in Macau (Macau: Centre of Macau Studies, University of East Asia, 1990), especially the map on p. 64; Jon Prescott, Macaensis Momentum, map following p. 21.

3 Prescott, Macaensis Momentum, p. 21.

4 See the discussion in Richard L. Edmonds, "Land Use in Macau: Changes between 1972 and 1983," Land Use Policy, vol. 3, no. 1 (January 1986), pp. 47-63.

5 See the interview with Jon Prescott reported in Arquitectura Macau, no. 4 (July/ August 1992), pp. 30-35. Many of the points made in this section originate from discussions with Mr. Prescott, particularly his presentations made to the class SOCI 300 at the University of Macau.

6 Richard L. Edmonds, Mapa de Macau: Utilização de Terrenos, 1983 (Macau, 1984).

7 In Arquitectura Macau, July/August 1992, p. 34.

8 The most obvious example of a building that stands out from its neighbors is the Bank of China, which is near to but not technically in ZAPE.

9 I have earlier commented at greater length on this point: Bruce Taylor, "As-sessing the Contributions of Historic Preservation in Macau to the Quality of Ur-ban Life," in B. Taylor et al., eds., Socioeconomic Development and Quality of Life in Macau (Macau: Centre of Macau Studies, University of Macau and Instituto Cul-tural de Macau, 1993). See especially pp. 244-245.

10 Technically, the plan shown in Figure 1 includes both the original NAPEreclamation and Zone B of the Nam Van project, which adjoins it. At the time of writing, the NAPE reclamation was completed and buildings were beginning to rise on it; the adjoining Nam Van Zone B was still rising from the sea. Eventually, though, the two areas should be indistinguishable from each other. Planning con-trols adopted in both sections of the reclamation appear to be identical.

11 The inter-island reclamation between Taipa and Coloane islands (the so-called "Cidade Cotai") will also be an area devoted to multiple uses. However, a plan for this area had not yet been adopted officially at the time of writing.

12 See, for instance, the four-page advertisement placed in the South China Morning Post, July 12, 1993.

13 It is interesting to observe that architects in Macau are asking questions regarding the rigidity of the planning regulations for NAPE, in order to determine the degree of latitude they might have in the design of individual structures (see Arquitectura Macau, July/August 1992, pp. 41-42.)

14 Prescott, Macaensis Momentum, p. 55.

15 Commercial space in the Baixa area of Taipa provides a cautionary example;there is much more street-front commercial space available at the time of writing than the limited local market demands, and more still to come.

16 In perhaps the most dramatic example, a development of single-family town-houses occupying a spectacular site overlooking Cheoc Van beach (Coloane Is-land) stood vacant for eight years while the developers sought permission to sell the units individually.

17 Victoria Finley, "The Biggest Gamble," South China Morning Post, January 29,1994.

18 Human scale, and other valued attributes of the historic city of Macau, are discussed at greater length in Taylor, "Assessing the Contributions of Historic Preservation ...."

19 In other parts of Macau buildings are "humanized" by virtue of ad hoc mod-ifications made by individual occupants (enclosure of balconies, installation of decorative grilles over windows, and the like). No doubt there will be regulations to prohibit such actions in the NAPE and Nam Van developments.