Migration and Development in Asia:From Sojourners to New Extended Familis*

Ronald Skeldon(Department of Geography and Geology University of Hong Kong)

The evolution of migration from Asia in general, and from Hong Kong in particular, to North America and Australasia is described. In the nineteenth century, this migration was mainly circular, of sojourners, consisting of males and labourers. In the late twentieth century, the movement is mainly of set-tlers, balanced between the sexes, most of them highly skilled. There is, how-ever, significant return migration of family members to Hong Kong and Asia. These migrants are creating trans-Pacific networks by establishing family members in at least two locations around the Pacific. People are organizing their movements within these networks, depending on economic and political circumstances. The tensions within these "diasporic families" are discussed.

Introduction

The last twenty-five years have seen tremendous change in levels of economic development in East and Southeast Asia and also in the volume and forms of popu-lation movements. Paradoxical though it may at first seem, the prosperity of the Asian populations has been increasing at the same time as more and more people have been leaving Asia. Migration from Asia is not new of course. Many thou-sands left China and Japan for North America and Australasia from the mid-nine-teenth century until these movements were slowed and eventually almost stopped by a series of restrictive immigration policies that were implemented by the desti-nation countries from late in that century. These remained in effect in practice, if not in theory, really until the 1960s. The migration out of Asia during the nine-teenth century was dominated by men whose intention was to return to their home-land after earning enough money in the new worlds. These were the sojourners. While many did return, others died at the destinations, and yet others were trapped through indebtedness or indifference in the labouring jobs and ethnic enclaves of the United States, Canada and Australia.

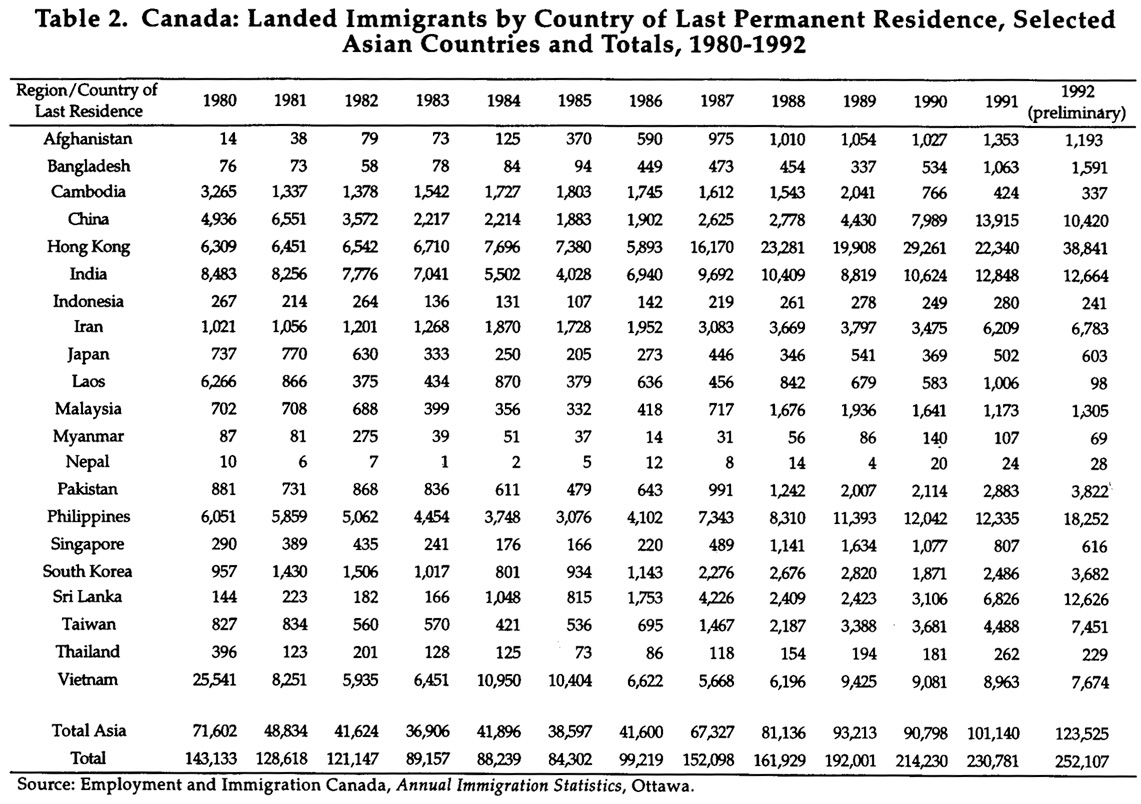

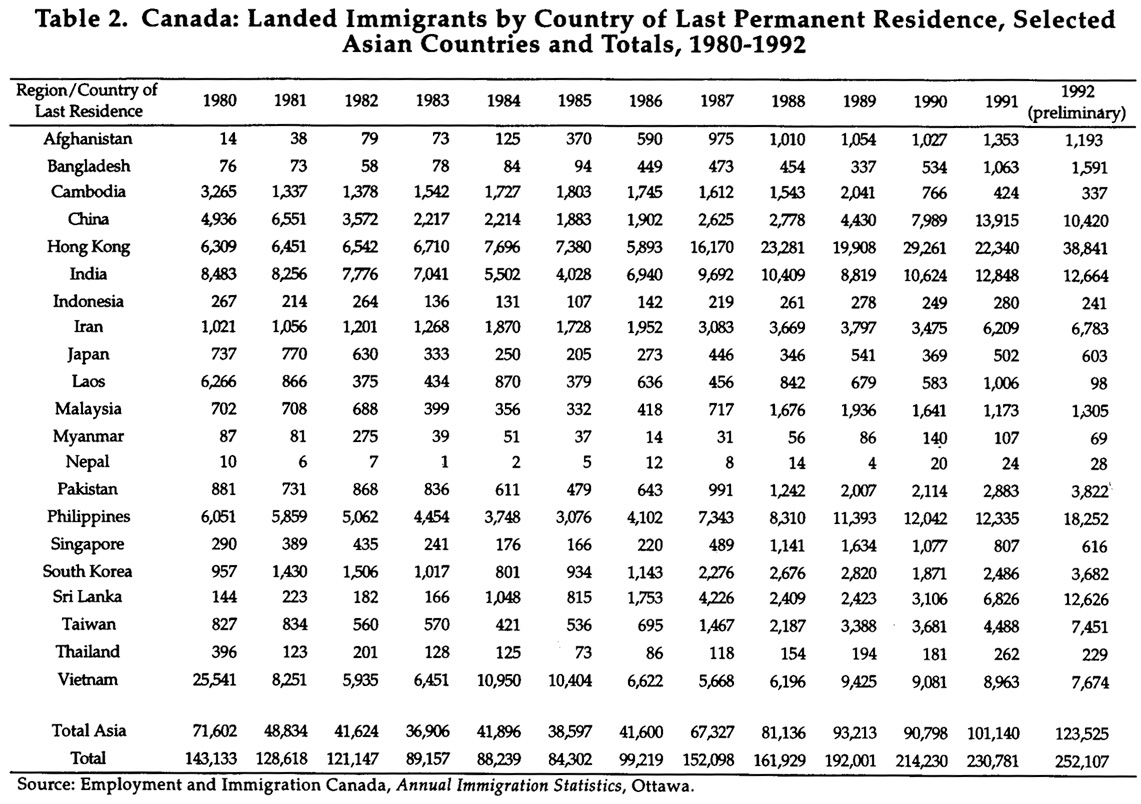

The new migration out of Asia over the last twenty-five years has been some-what different. Indeed, there have been "neo-sojourner" movements of predomi-nantly male labourers to the oil-rich countries of the Gulf states but there have also been movements of highly educated men and women to North America and Australasia. These people are being accepted into Canada, Australia and the United States as settlers. From accounting for about 5 per cent of the annual intake of immigrants to these countries in the early 1960s, Asians were accounting for be-tween 40 and 50 per cent of immigrants in the early 1990s.

This migration of the highly educated and skilled has been of concern to ori-gin countries as a "brain drain" from their labour forces. Nowhere has the con-cern been greater than in Hong Kong, where concern over the British colony's return to Chinese sovereignty on 1 July 1997 has been seen as a factor in account-ing for the increasing outflow of the population. During the first half of the 1980s, the annual numbers leaving Hong Kong were around 20,000 but this figure had increased to around 60,000 by the 1990s. Large numbers have, however, also been leaving South Korea, Taiwan, Singapore and China itself (Tables 1, 2 and 3). While the trend in the numbers appears clear enough in the tables, there is a question mark over the real implication of, for example, 16,747 Hong Kong permanent resi-dents arriving in Australia during financial year 1990-91. Certainly, that would have been the number arriving with settler visas in Australia during that year but, of these, how many have actually taken up residence there and are living there permanently? There is now sufficient evidence to suggest that large numbers are returning almost immediately to their home areas but also that we are seeing the emergence of new forms of extended households, with family members spread between two and possibly three widely separated places.

The major problem is to obtain figures that are accurate enough to provide esti-mates of the volume of return movement and of split households. Neither Canada nor the United States keep records of the numbers of residents leaving and, although Australia does maintain such statistics, these have not yet been made available in a way to permit useful analyses. Much of the evidence is anecdotal or comes from micro-level studies of small numbers of migrants such as the work of Larry Lam in Toronto (Lam, 1994). The first concrete data have come from Australia, although cau-tion must be exercised as we are comparing here two different data sets which really cannot be directly compared. However, despite their limitation, the data do allow a first look at the importance of population turnover (Table 4).

Return Movements1

The 1991 census of population of Australia collected information on year of arrival of the overseas-born. This can then be compared with the information on settler arrivals adjusted to calendar years. There are problems associated with this method related mainly to misstatement in the census data, which also failed to separate from the immigrant population students and others on temporary visas. Also, the information on settler arrivals applies only to the first six months of1991 while the census was taken on 6 August;that is the settler arrivals for the period 1990-91 are understated by about five weeks,or perhaps 6 percen.

Table 4. Hong Kong-born Migrants by Year of Arrival in Australia, 1986-1991 Census and Immigration Data Compared

Year of Arrival Census Settler Attrition

Arrivals %

1986 and 1987 6,975 7,520 7.5

1988 and 1989 13,720 14,412 4.8

1990 and 1991 12,109 17,560 30.0

1986-1991 Total 32,804 39,511 17.0

Sources: Unpublished tabulations, 1991 Census of Australia; Overseas Arrivals and Depar-tures, Australian Bureau of Statistics, various years.

Immigration data show that 39,511 people bom in Hong Kong arrived in Aus-tralia between 1 January 1986 and 30 June 1991. The 1991 census records 32,804 Hong Kong-born in Australia who had arrived since the beginning of 1986. There had thus been an "attrition" of 17 percent through death, onmigration, or return migration. Given the youthful age structure of the Hong Kong-born population, mortality over the five-year period can be assumed to have been low, and we can safely conclude that the main cause of the reduction was return migration to Hong Kong.

The most significant trend apparent from the data is the marked difference in attrition between recent arrivals (since 1 January 1990) and those who arrived be-fore that date. Given that the count of immigrant arrivals for this period is under-stated, it appears likely that about one-third of those who arrived as settlers from the beginning of 1990 have returned to Hong Kong. Between 1 January 1990 and 30 June 1991,17,560 Hong Kong-born settlers arrived in Australia, but only 12,109 Hong Kong-born residents of Australia on 6 August 1991 said that they had ar-rived during 1990 and 1991. We can reasonably assume that over 5,000 of the set-tler arrivals had returned to Hong Kong by the end of the eighteen-month period. Attrition rates for the four previous years were much lower, at between 5 and 7 percent. This suggests that recent Hong Kong migrants have returned quickly and have not waited to obtain full Australian citizenship. If we could control for the presence of students and temporary migrants in the census figures, it is likely that the attrition rates would be even higher. However, despite the disadvantages with the approach, these data do give some substance to what has been purely impres-sionistic and anecdotal information on return movement.

The rapid turnover of Hong Kong migrants to Australia may not be typical of the migration to the other major destinations. On landing in Australia, a settler ob-tains a multiple re-entry visa valid for three years. Hence, although from the age-sex structure of the Hong Kong-born in Australia (discussed below) it is clear that men are leaving families there, it is also likely that whole families are returning to HongKong. They can do this legally for up to three years. Then, before the expiry of the re-entry visa, they must return to Australia for at least twelve months before obtaining a further re-entry visa. Hence, the flexibility of the Australian regulations has al-lowed large numbers of Hong Kong people to obtain an "insurance policy" while they wait and see how Hong Kong's economy develops in the lead-up to 1997. Such flexibility is not available to migrants to Canada or the United States.

The New Extended Families2

Although return movements may be high, it is the other form of mobility that is most intriguing: the establishment of families separated by great distances. Here we are dealing with a relatively small number of migrants who are highly edu-cated and very wealthy and whose significance far outweighs their numbers. These dynamic people with money to invest often, although not exclusively so, join busi-ness and entrepreneur migration programmes that have been devised by the Australian, Canadian, New Zealand, and United States governments. Wealthy or highly skilled emigrants who do not move within these programmes can usually easily qualify for evaluation in the independent migrant categories which are geared toward taking the "best and the brightest." In the late twentieth century, business requires mobility - mobility in the sense of quickly shifting assets from one sector to another and from one place to another, but also mobility in terms of the individual entrepreneur. The idea that business interests can be associated with settle-ment is contradictory (Smart, 1994). Business people need to be able to oversee their investments no matter where they are, and these investments are unlikely to be concentrated in one city or even one country.

Thus has the modern sojourner evolved: the person who commutes or circu-lates over long distances with place of residence in Canada or Australia but place of business in both North American and Asian (or other) locations. This scenario can also apply to the highly paid professionals and even bureaucrats who have technically "settled" in Canada but continue to work in Hong Kong. These are known as "astronauts," a term from the Chinese taíkongren, which felicitously combines the English meaning of a person who spends time in space, that is, an aeroplane, with a Cantonese play on words around "empty wife," "home without a wife" (in Hong Kong), or "house without a husband" (at the destination).

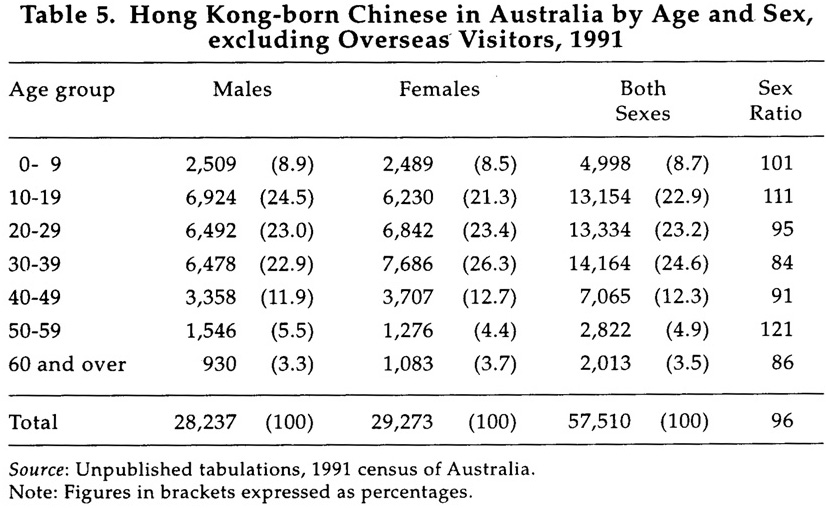

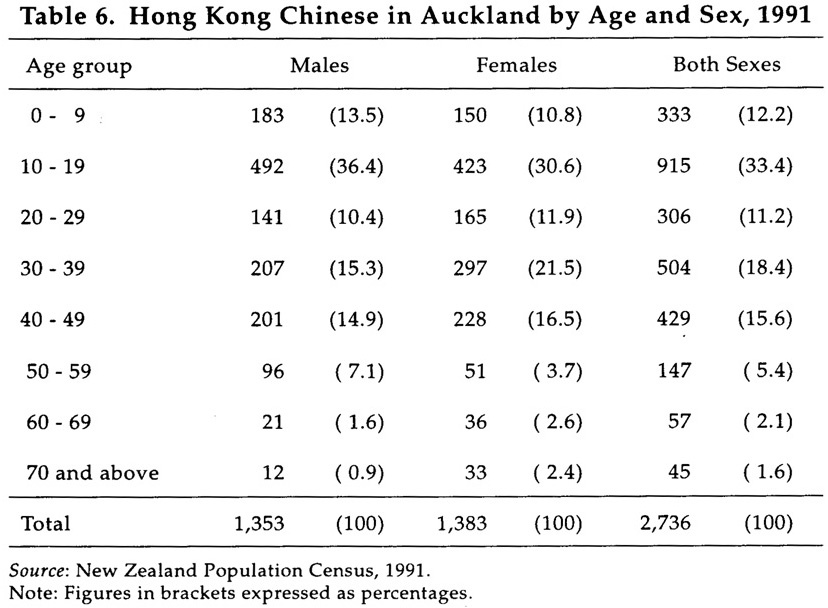

There are, as yet, few reliable data to assess just how important this type of long-distance commuting might be. However, recent information from the 1990 round of censuses in Australia and New Zealand suggests that it is significant. The data are particularly interesting for Australia as indications of the importance of the movement appear at the national level. The information discussed below relates to the age and sex structure of the Hong Kong-born in Australia and in Auckland, New Zealand.3

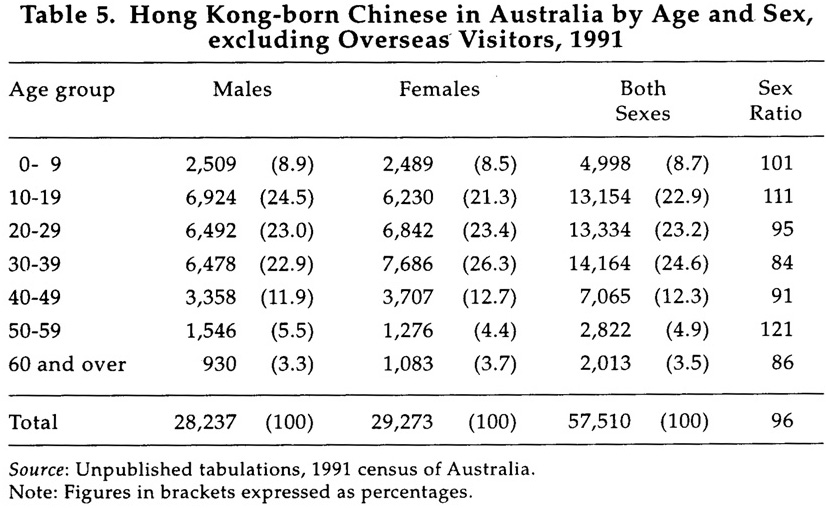

The age-sex structure of the Hong Kong-born in Australia is shown in Table 5. While the age profile does bear some semblance of a classic migrant structure, with relatively few in the youngest and oldest cohorts, there are important devia-tions from that ideal. There are more people in the cohorts below 20 years of age than in the case of the population of Hong Kong itself, showing the importance of young people moving or being moved to Australia for their education. The 10-19 years cohort, as well as the older 50-59 years age group, are the only ones that are markedly male, which suggests that, in the case of the younger cohort, more boys than girls are being sent to continue their education. The mature adult cohort of 30-39 years conversely is markedly female-dominant. This is the age group in which the professional heads of family are most likely to be found; here is evidence of the wives being left in Australia while the husbands return to Hong Kong: the "astronaut" syndrome.

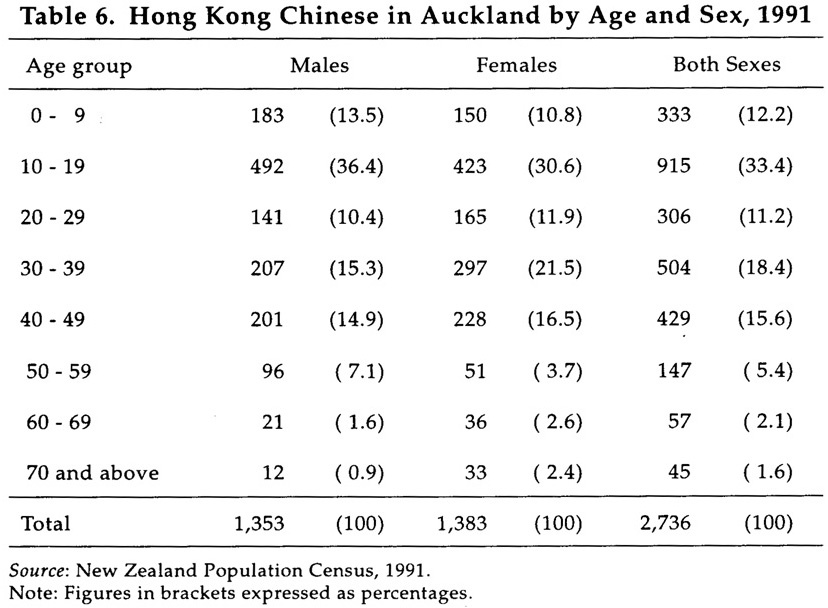

The trends for Auckland are, as one would expect for a smaller geographic area, much more marked. A total of 45.6 percent of the Hong Kong Chinese in Auckland were under 20 years of age, 50.6 percent were in the 20-59 years age groups, while only 3.7 percent were 60 years of age and over. The age selective-ness of migration is reflected in the data (Table 6). Also clear is the strong domi-nance of females in the 20-49 years age groups, which is suggestive of the "astronaut" syndrome: significant numbers of female-headed households established in New Zealand with the male back in Hong Kong. However, further research on female-headed households will be required before more definitive conclusions can be drawn. There is also a substantial proportion of young people: fully 45.6 percent of the sample were under 20 years of age compared to 29.2 percent for the Hong Kong population in 1991. These data from New Zealand and Australia are, hence, clearly suggestive of the importance of "parachute kids" and "astronauts" in the migration flows out of Hong Kong.

Discussion

The importance of return movements and of the long-distance commuting within extended family networks in the recent migration out of Asia is clearly a function of the rapid development of the Asian economies themselves. The East Asian economies, excluding Japan, are booming relative to the stagnation of North American, Australasian and European economies. Unemployment is currently in excess of 10 percent of the labour forces in Canada and Australia compared with virtually no unemployment in East Asia and severe labour shortages in Korea, Taiwan, Hong Kong and Singapore. Yet, this economic argument is altogether too simple. The Asian migration can be seen as a risk-minimization strategy. The mi-grants are minimizing political risk in that the families are resident in areas of perceived stability while the principal breadwinners continue to work in Asia. Very quickly, they would be able to rejoin their families on a permanent basis should political conditions in Asia change. This strategy also allows the migrants to spread economic risk by having access to business and job markets in two different loca-tions which may be at different stages in the business cycle. When growth slows in Asia and accelerates in North America, then greater attention can be shifted to the latter and vice versa if conditions change again. Thus, family members can"flow" within the networks among very different economies and societies.

This type of "diasporic family" is part of the pattern of the new migration from Asia. It is realized only with the existence of modern rapid forms of commu-nication, both in business and in transportation, and hence is a unique develop-ment of these new Asian migrations and the modern world. There are, however, important tensions: within the families themselves due to periods of separation of one spouse from the other and of parents from children, and also of cultural and national identity. Children are growing up in different culture areas from at least one parent. Breadwinners are being admitted to countries as settlers, as future Canadians or Australians, and yet are spending much of their time in origin areas. This bilocality raises intriguing questions of national loyalty of relevance to im-migration policy. Whether pan-national loyalties are evolving that "fit" more eas-ily with global economic systems must await future analyses.

This short paper draws on work currently press in Skeldon (ed.)1994.The specific sources are indicated at the appropriate points in the text .Any citations acknowledge the original source and the publisher,M.E.Sharpe.

Notes

1 This section is taken from Kee and Skeldon, 1994.

2 This section is taken from Skeldon, 1994.

3 These data are taken from Kee and Skeldon, 1994, and Ho and Farmer, 1994.

References

Ho, E. S. and R. Farmer. 1994. The Hong Kong Chinese in Auckland, ed. by Skeldon, q. v.

Kee, Pookong and R. Skeldon. 1994. The Migration and Settlement of Hong Kong Chinese in Australia, ed. by Skeldon, q.v.

Lam, L.. 1994. Searching for a Safe Haven: the Migration and Settlement of Hong Kong Chinese Immigrants in Toronto, ed. by Skeldon, q.v.

Skeldon, R.. 1994. Reluctant Exiles or Bold Pioneers: An Introduction to Migration from Hong Kong, ed. by Skeldon, q.v.

Skeldon, R. (ed.), Reluctant Exiles? Migration from Hong Kong and the New Over-seas Chinese, (New York and Hong Kong: M. E. Sharpe and Hong Kong University Press, 1994).

Smart, J., Business Immigration to Canada: Deception and Exploitation. 1994, ed. by Skeldon, q.v.