The Challenge of Buddho-Taoist Metaphysics in East-West Dialogues

Kenneth K. Inada

〔提要〕盡管有人否認,我們還得承認:我們對經驗主義和理性主義所持的偏見,限制了我們對事物本身的認識。現在有必要檢討我們認識論的基礎,進而探討認識事物的泉源。一旦把我們的探索轉向東方,尤其是佛教——道教玄學,即至少有兩項收獲;第一,明瞭情境決定認識;第二則可開展理智的論說和對話。

經驗主義的軌迹本源於生成的本質。不過,西方的論說多基於“存在”的概念;而東方則基於非“存在”的概念。這一分界就從諸方面說明了東西文化間種種微妙的差異。事實上,“存在——非存在”之爭,過去從未徹底搞清楚,而今天該是解決的時候了。

本文試闡述“非存在“概念的特性,然後找出爭論的實質,望能為豐碩、有成效的討論和對話拋磚引玉。

The concepts of being and becoming are basic to our perception and understanding. They are the pillar metaphysical concepts in which our modes of perception are framed. Yet, interesting enough, it has not occurred to many that these concepts do not exhaust the categories in which we frame our knowledge of reality. One of the factors that prevents us from moving out of this limited metaphysical orientation may be traced back to the Greek tradition in which Piato argued cogently for the absolute nature of things, i. e., the nature of being over becoming. His arguments were quite persuasive, to say the least, for anyone is enthralled by the characteristics of permanence and absolutism in contrast to impermanence and relativism. So from the outset, a metaphysics based on the concept of being became the guide to ali empirical, rational and logical understanding; at the same time, the concept of becoming or change was relegated to a secondary position because of its relative and dependent nature of things. Thus the bifurcation of nature, being and becoming, or, more precisely being over becoming, began early in the Westem tradition and has continued to the present without arousing serious questions concerning its function and value. Along its way, thinkers were given free reign to concentrate on the permanent and enduring entities with which the empirico - rational modes of perception could function effectively. The results have been dramatic, especially in the scientific and related fields.

We still think and act Platonically owing to the fact that Plato’s metaphysics lends itself readily to scientific methodology. Yet, time moves on and we have already seen great perceptual changes occurring over the centuries. One of these changes in the modem period was the cosmological shift occasioned by the replacement of Ptolemaic theory by the Copernican. It was a huge break for science in general as it engendered new insights and discoveries. One of these insights came in the form of Newtonian physics which gave a new perspective to understanding the universe. And within this new physics, science and related fields were given a new lease on their innovative methods and procedures. All of this eventually resulted in another momentous development in the form of Einsteinian physics. The movement from Newtonian to Einsteinian physics is not only remarkable but dramatic, i.e., it caused a real shift in our orientation from the nature of being to becoming, from the absolute nature of things to the relative. Einsteinian physics opened the doors to a truly dynamic world but, ironically, the public was ill-prepared to accommodate it.. Indeed, our ordinary perception of things, both in the microscopic and macroscopic realms, is still oriented in a Newtonian world rather than Einsteinian. We still perceive and understand things on the basis of absolute, permanent and enduring entities within the spatio- temporal context. The reason for this is not hard to find. The Newtonian world is far easier to grasp conceptually than the Einsteinian and readily conforms to our rational and logical analysis of things. Moreover, our ordinary perception easily adapts to such analysis. The Einsteinian wortd, on the other hand, is roo abstract, relative and dynamic for the average mind to cope with. It does not blend with ordinary perception of things despite its universal appeal and acceptance by the scientific community. It can further be said that our ordinary perception is ill- equipped to follow the subtle principles of relativity in both the microscopic and macroscopic realms of existence. We are, in short, burdened by a historical lag caused by a mode of perception steeped in substance-orientation, one which refuses to completely harmonize with the constantly changing conditions. We therefore find ourselves in a bind or quandary. We face a dilemma so Iong as we maintain the strict dichotomy of being and becoming or being over becoming. How can we resolve the dilemma? Or, how can we reverse the order, from being to becoming? Needless to say, we need to open up new vistas, a vew horizon and depth Of perception. We need to venture beyond our Western tradition,for example, to examine the Asiatic metaphysics nascent to Buddhism and Taoism.

In many respects, the Buddhist and Taoist had anticipated an Einsteinian world for centuries, if not for several millenia, and had gone very far in incorporating a world of becoming. The various cultural accomplishments, such as, music, poetry, painting and literature exhibit the effectiveness and fruitfulness of a fluid and dynamic nature of life. The basic principles and doctrines attached to becoming were spawned simultaneously in the Indian and Chinese civilizations which have continued to assert themselves to the present. Although these civilizations in recent centuries have lagged behind the West in science and technology, their cultural achievements and consequent impact on humankind are inestimable. What then makes a civilization or culture viable? The answer is quite complicated, to be sure, bur a clue seems to point in the direction of the nature of human experience. In other words, in what unique manner does experience function? Or, what is the metaphysical grounding for the rise of the special mode of perception? In seeking ah answer, we are brought back to Buddhism and Taoism. These systems have molded a large segment of the Asiatic mind with their incomparable metaphysical basis of experiential reality, just as Greek philosophy has been the single most influential force in the making of the Western mind. Since both systems focus on and function from similar experiential grounds, I have grouped them together in delineating a Buddho - Taoist metaphysics, although admittedly any scholar would be wary, and rightly so, of identifying them in the strictest sense.

It should be pointed out at the outset that Asiatic metaphysics is not limited to the concepts of being and becoming for it also involves a third member, nonbeing. To the uninitiated, nonbeing is a concept not normally taken seriously; to the Asiatic, however, it is a pivotal concept, the true underpinning of all experiences, As stated earlier, the Asiatics were already Einsteinians in the sense that they maintained becoming to be the most basic and primitive nature of experiences. In other words, experiences take places as a becoming process, not in terms of static natures, and that any substantive accounting of experiences would take on secondary characteristics which are in the final analysis superficial and abstractive of the reality of things. So with becoming as the experiential basis, being and nonbeing become two rubrics of the function of becoming. It is worth noting that where the West expanded and envisioned becoming in terms of the nature of being, the East (Asia) took becoming to be fundamen ally in the nature of nonbeing. Plato’s metaphysics, as seen earlier, best illustrates the Western development of perception and understanding centered on the nature of being. In contrast, the Eastern metaphysics is best represented by a Buddho - Taoist metaphysics which focuses on the natureof nonbeing. The difference is dramatic bur the consequence of which has not been fully known nor appreciated by the West so far, except that we are witnessing a gradual acceptance and understanding of the unique nature of Asiatic thought in general. This is a hopeful sign which should lead one on to probe deeper into the profound metaphysics inherent to Asiat-ic philosophy.

As matters stand now, we need to take a radical stand, to engage in a radical interpretation of our perceptual apparatus and consequent understanding of things as such.

The nature of becoming in Buddhism is represented by the concept of impermanence (anitya) or momentariness (ksanikatva) and in Taoism by the general concept of change (yi) or selftransformation (t’u hua). In China, the text, Yi-Ching (Book of Changes), has been most influential in molding the Chinese mind. Even Confucius did not deviate from this concept of change in developing his philosophy. Taoist thinkers took off with this concept and wholeheartedly utilized the dynamics of yin- yang to refine the subtle doctrines inherent to the Tao or the Way of Nature.

In order to probe Eastern metaphysics further, I shall reler to it as intuitive and depth rnetaphysics. It is “intuitive” in the sense of bringing into play the total empirical and rationaJ function within the context of becoming and “depth” in the sense of probing deeper into the realm of experiential (becoming) reality, lntuition is the gateway, so to speak, in terms of discovering the real nature that underlies empirical and rational data or how the data themselves exist; however, much of our understanding of such data had been perfunctory by merely allowing the rules of logic and ordinary nature of perception of things to govern our experiences. We still base our ordinary perception of things within the context of being and construct or establish rules of operation within that context. In consequence, should anything or any element fail to conform to such a context, it will either be ignored or rejected. In this way, we discard much of our experiential reality in the nature of becoming. We must of course retrieve or restore what we discard. Indeed, it would be much better to realize a situation where discarding and retrieving do not apply at all. This is where intuitive depth metaphysics come to the fore.

In truth, our ordinary experiences have contents which are much fuller and deeper than what is reported by our senses, including the mind. We have taken for granted that perception and perceptual data are always in proper order and function, and are reliable in everyday living.(1)But this is concerned with “surface” perception. We need to probe deeper into the makings of perceptions themselves in order to appreciate their total holistic nature. Like being enthralled by the nature of the proverbial “tip of the iceberg,” we have glossed over the deeper setting and more significant aspect of perceptions.

The depth metaphysics intimated by the Easterner reveals a new dimension to experiential reality which is subtle and novel. To the surprise of many, it is depicted as nonbeing. Nonbeing has always been an important component of ordinary experience for the Easterner from the beginning. By contrast, the West had early on either rejected nonbeing outright or relegated it to a secondary realm of existence if at ali. The dichotomous mood of the West had, generally speaking, dismissed nonbeing to a valueless non - category bin.

To be more precise, the concept of nonbeing is strictly a Western term which we use in opposition to the concept of being, where the former has a negative connotation and the latter positive. If this were all that can be said of nonbeing, then unfortunately, we will have fallen into the trap of dichotomy, a trap we have cautioned against. Indeed, the Western concept of nonbeing does not fully describe the Buddhist and Taoist notions relative to the subtle dimension of experiential reality, Techincally, the Buddhist notion in Sanskrit is  nyatá which is variously translated as emptiness, nothingness, voidness, etc., and the Taoist notion is wu, variously translated as nothingness, vacuity, nonentity, etc. Wu and

nyatá which is variously translated as emptiness, nothingness, voidness, etc., and the Taoist notion is wu, variously translated as nothingness, vacuity, nonentity, etc. Wu and  nyatá are not identical, to be sure, but they are quite similar in terms of playing the role of effectuating or achieving the holistic nature or grounds of experiential reality. In this respect, they deny any primacy and prominence to the concept of being. But, on the other hand, they penetrate and absorb the realm of being. This inner dynamics of being in the realm of wu or

nyatá are not identical, to be sure, but they are quite similar in terms of playing the role of effectuating or achieving the holistic nature or grounds of experiential reality. In this respect, they deny any primacy and prominence to the concept of being. But, on the other hand, they penetrate and absorb the realm of being. This inner dynamics of being in the realm of wu or  nyatá has always been the starting point as well as the end of all experiences. The Chinese, over the centuries, were able to understand the true import of Buddhist

nyatá has always been the starting point as well as the end of all experiences. The Chinese, over the centuries, were able to understand the true import of Buddhist  nyatá and incorporate it into their own Taoist concept of wu. As a consequence, wu and

nyatá and incorporate it into their own Taoist concept of wu. As a consequence, wu and  nyatá (Chinese k’ung) were interchangeable concepts but the Chinese preferred to express the true holistic experience by wu. For our discussion, however, I shall revert to the currently used term, nonbeing, with the understanding that hereafter it refers specifically to the deep metaphysical dimension of Buddhist andTaoist experience.

nyatá (Chinese k’ung) were interchangeable concepts but the Chinese preferred to express the true holistic experience by wu. For our discussion, however, I shall revert to the currently used term, nonbeing, with the understanding that hereafter it refers specifically to the deep metaphysical dimension of Buddhist andTaoist experience.

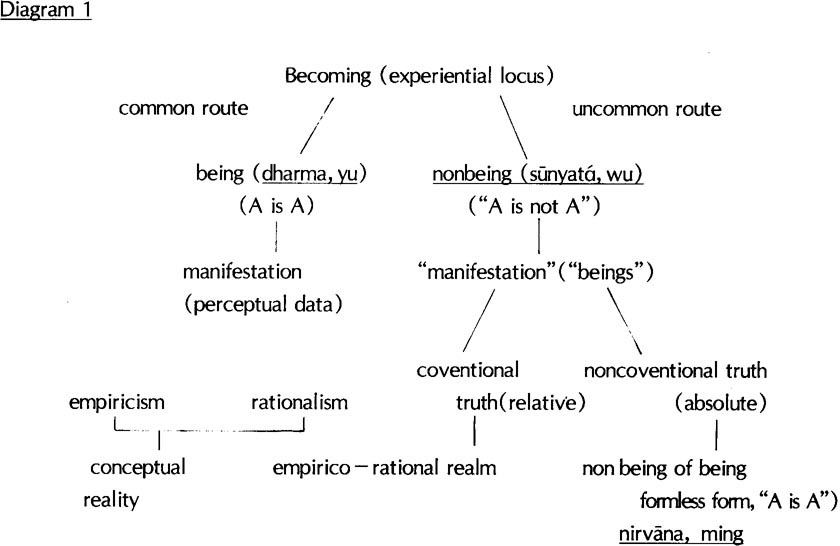

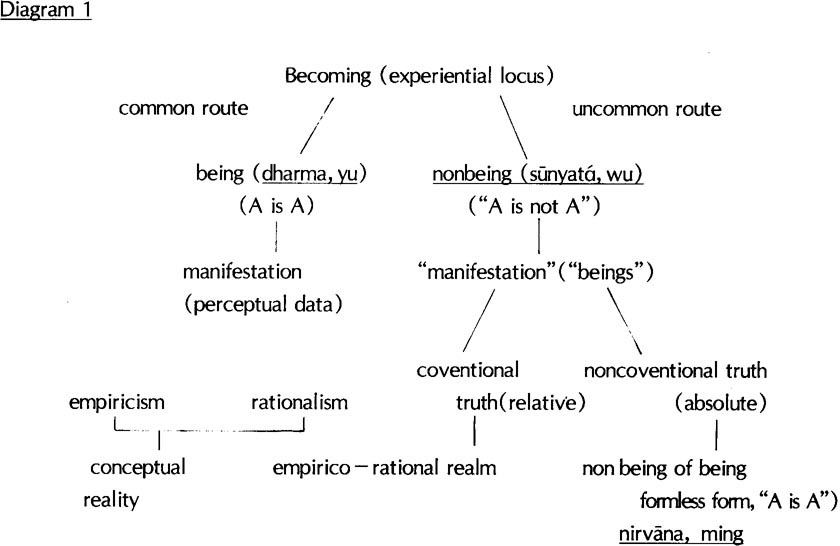

A rough sketch (Diagram 1) will exhibit the two routes taken, common and uncommon, in our perception of things. Both start with the nature of becoming, but where one side quickly orients everything within the context of being, the other side begins and ends with the nature of nonbeing. The implications are legion. One side thrives on the finitude of things but the other on the non - finitude of things. Both sides manifest but in different ways. Where one side indulges in the analysis of perceptual data due to the concentration on the finitude of things, the other probes the very foundation of such data in order to manifest the fuller nature of their existence. In other words, where the common route explains and understands the manifested data in terms of our empirical and rational faculties, the uncommon route based on nonbeing sees the alleged “manifestations” as reference to conventional (relative) and nonconventional (nonrelative or absolute) realms of truth. The realm of conventional truth, naturally, is elaborated by ordinary empirical and rational analysis but the nonconventional realm does not lend itself to any analysis because there are no tangible data existing independently or separated from experiential nature. Moreover, the nonconventional realm is the ground for the highest form of knowledge- -the knowledge of no-knowledge in Taoism or simply ming (illumination )and in Buddhism the knowledge of nonattachment or nondiscrimination (praijñā) or simply nirvana. These are odd statements but they depict the primary nature of knowledge prior to the rise of any form of dichotomy.(2)

It should be noted that no amount of clarifying or refining the common route with empirical and rational analysis will ever cause commensurability with the uncommon route. There are various reasons for this but the most basic is the fact that the concept of being with its delimiting nature cannot incorporate nor implicate the realm of nonbeing. The reverse however is a distinct possibility, i.e., the nature of nonbeing can and does incorporate the realm of being because of its wider, deeper, resilient and open character. Indeed, the incorporation of being by nonbeing is the principal reason for the name, depth metaphysics. It is but another way of pointing to the final truth of things as a phenomenon in which beings are nestled in the nature of nonbeing. In consequence, commensurability is a concept acceptable not from the nature of being but from nonbeing. Unless this radical metaphysical posture of nonbeing becomes the center of all experiences, the results would be inconclusive in their narrow, limited and truncated natures.

Returning to Diagram 1, the difference between being and nonbeing could be illustrated by resort to the classical use of Zen logic. (3)A is A is the normal way our minds function. But the Zen master is quick to point out that this is ordinary thinking based on the concept of being. (4)He wants us to go beyond such thinking because true natue of thinking is more existential (i. e., covers more “ground”) than the merely clearly defined but delimiting results aspired for by ordinary thinking. Thus he introduces the seemingly absurd statement, “A is not A.” This is only to advance the fact that A is A shoutd be seen or perceived within the larger and deeper context of nonbeing. Or, put another way, A is A makes sense only when the beingness of A is seen from the aspect of its nonbeingness, i.e., negation or denial of its independent status, which then immediately opens up the more - than - A dimension of existence. In a graphic sense, the A is seen like an embossed letter which is s haded to accent its appearance bur knowing full well that its shaded areas are basic to the reality of experience.

It is important to note that the uncommon route ultimately ends in the nonconventional truth which expresses itself in paradoxes, e.g., nonbeing of being or formless form. In the tanguage of the Zen master, this is expressed as “A is A” in quotes in contrast to simple A is A. Here “A is A” is known from the aspect of nonbeing or emptiness(sūnyatā or wu) of things, a knowledge that befuddles the mind because our habits of perception are oriented in the strictly empirical and rational scheme of things ora combination of both. In this orientation, the results are definitely confined to conceptualization of the manifested data, hence conceptual realities. Indeed, for the most part, we are satisfied with the conceptual process and unconcernedly perpetuate our habits of perception.

The other side of nonconventional truth is of course the conventional truth, (5) both of which stem from the so - called “manifestations” of nonbeing. The difference here is between the absolute and relative natures or the holistic and the fragmentative. Our common understanding, based on conceptual realities, is entrenched in conventionality and relativity.As seen in Diagram 1, it is the realm of the empirical and rational which we have accepted uncritically as the absolute basis of truth. Furthermore, from this realm we have digressed even further into various forms of truths, such as, coherence, correspondence and pragmatic or their combination. These forms have been quite attractive and appealing to the average intellect. Yet it is at this point that the Easterner would stop to caution against facile acceptance of any truth without exploring the real basis of things or without perceiving the holistic realm from which all entities arise. In essence, we have attached ourselves to the relative nature of things as if the holistic (absolute) nature does not exist at all, just as in the classic metaphor where one has confused the trees for the forest, Our experiences are much fuller (holistic) than we normally take them to be. We have been carried away by simple and clear perception which feeds on the relative nature of things but which nature is actually engaging in an abstractive process with respect ot the pristine wholeness of experience. But surely, at this point, questions on the wholeness of perceptual process will arise. How can the whole coexist with the particular? Or, how can the particular leave the whole intact and still engage in the perceptual process? In brief, what is the status of the absolute and relative?

These questions, I believe, bring us back to the problem of accommodating the functions of epistemology and metaphysics. Their functions are actually an intimate involvement of both. For example, each epistemological function is an instance of its involvement of a metaphysical entity and, vice versa, each metaphysical entity is an instance of its involvement in (or the result of) an epistemological function. Both are vitally and dynamically involved in an interpenetrative sense but(6), generally, we have split them into neat well - defined disciplines and are unmindful of the fact that they basically constitute an experiential unity. Cartesian meditations could be interpreted as instances of refining both the epistemological and metaphysical nature of things at the expense of the basic experiential unity. The derived cogito (I think) is actually not ergo sum(therefore, I exist) bur the reverse, i.e., I exist, therefore I think. In other words, the existential grounds are always greater than the thinking grounds. What can be thought, certainly, can be thought, but it is not the case that what cannot be thought cannot exist. Indeed, paradoxical as it may seem, what cannot be thought could be the basis of what can be thought. This kind of reasoning has not had the chance of being implemented in ordinary logic. But in Eastern ways of thinking, it is common knowledge that the that which cannot be thought (e. g., nature of nonbeing ) is constantly implemented in dealing with manifested beings and, in this sense, any epistemological function immediately involves the total metaphysical grounding of experience. Put another way, for the Easterner, the epistemic nature always presupposes and implicates the nature of nonbeing. In this way, the being - nonbeing dynamics is secured but ordinary minds are, unfortunately, unaware of the presence of this dynamics, nor are they knowledgeable about how to implement it. The Easterner naturally is keen about the presence of being - nonbeing dynamics although in everyday living process he or she does not directly refer to it as such, nor speaks of it in clearly defined terms. In many respects, it cannot be delineated simply because the unity of experience defies logical analysis or precision. To expand on this point, we return to the diagram.

The nature of being in Diagram 1 needs to be elaborated. The Buddhist and Taoist have, respectively, labelled being as dharma and yu. A dharma has been translated variously as “element of existence,” “element of being,”“factor of experience,”“phenomenon,”“perceptuai datum,” and “perceptual reality.” It carries a special meaning in Buddhism as contrasted with its standard usage by the Hindu and Jain who depict it as a norm of behavior or value attached to ethical conduct of the highest order. The Buddhist did not of course lose sight of this norm of behavior in that the term, dharma, was also used for the true nature of existence, the Dharma in capitalized form. The Dharma in this sense, constituted one of the triads of Buddhist Treasures, i.e., Buddha, Dharma and Sangha. That the same term is used to describe two entirely different phenomena is truly an unique feature of Buddhist thought. But this feature is well taken as we hark back to the being - nonbeing dynamics where dharmas are, in the final analysis, absconded in the total nature of enlightened existence. Thus a dharma - Dharma functional scheme was developed early on in Buddhism by the Abhidharma schools which postulated from 75 to 100 dharmas. No time to elaborate on these dharmas bur suffice it to say that the scheme made a categorical distinction between “created or manipulated” (samskrta) dharmas and “uncreated or nonmanipulated” (asamskrta) dharmas, the latter of which made way for rhe enlightened realm of existence. Consequently, a parallel can easily be seen inthe being - nonbeing and dharma - Dharma dynamics.(7)

In many respects, the Abhidharmic thinkers were the first to come to grips with an elaborate psycho - physical scheme to analyze the multiple factors or phases of our experiences but constantly keeping in mind that those factors or phases all belong to, indeed interact within, the total holistic nature of existence. The whole Mahayana movement did not drastically deviate from this dharma - Dharma dynamics. If anything, it made very good use of the dynamics as seen in the development from the prajñápáramitá through Mádhyamika and Vijñánaváda thinkers. Subsequent developments in Tibet, China, Korea and Japan all worked within the dynamics, albeit modifying and crystalizing the epistemic nature of things framed within their respective cultural backgrounds. Variant forms of Buddhism existing in the world today attest to and confirm its strength, flexibility, fluidity and continuity.

In a similar vein, we find Taoist dynamics involving being (yu) and nonbeing (wu) revealing its uniqueness. The first verse of the Tao Te Ching states:(8)

The Nameless is the origin of Heaven and Earth;

The Name is the mother of all things.

Therefore, let there always be non - being so we may see their subtlety,

And let there always be being so we may see their outcome.

The two are the same,

But after they are produced, they have different names.

The two (yu and wu) are intricately interwoven, one side is visible (“outcome”) the other invisible (“subtlety”). But both make up the total realm of experiential reality, although in different ways. Yet, it seems that our dichotomizing nature quickly divides that reality into neatly defined categorical concepts and maintains them as such throughout our ordinary perception of things, Lao Tzu and Chuang Tzu are united in focusing on the major concept of change (yi or hua) rather than on being and nonbeing. For example, Chuang Tzu’s famous dream of the butterfly ends thus:(9)“Between Chou and the butterfly, there must be some distinction. This is called the transformation of things.” Even in the subtle realm of dreaming, the dynamics of change involving being and nonbeing is ever functioning and Taoism simply challenges us to explore the deeper nature of the dynamics itself.

The challenge is indeed difficult to take up, so long as we remain conditioned by our ordinary bifurcated nature of existence. The starting point might be: (1) to realize that there are alternative ways of experiencing reality as such or the truth of existence and (2) to institute a dramatic categorical shift in our epistemological function, a function that not only entails the inclusion of the realm of nonbeing in dealing with the ordinary nature of being but also to savor the primacy of nonbeing over being. Althought the being - nonbeing dynamics is as old as Buddho - Taoist metaphysics, it has yet to have its full day in court in our contemporary world of thought.(10)

CONCLUDING REMARKS

The discussion has brought forth several points:

1. We need to get our metaphysical priorities in order. All perceptions and subsequent understanding must be focused on, indeed framed within, the becomingness of things. It means that rather than being, becoming is the first order of things.

2. As becoming is at all times the center of discourse, all subsequent discussions on perceptions involving being must also involve the hitherto neglected nonbeing, the singular contribution of Buddho - Taoist metaphysics. Both being and nonbeing seek their sources in becoming.

3. The nature of becoming is dynamic in the sense of involving both being and nonbeing, thus a being - nonbeing dynamics which is the foundation of Buddho - Taoist metaphysics.

4. In the discussion, we have seen that being cannot involve nonbeing, but the reverse is possible, i.e., nonbeing can and does involve or include being. This is so because nonbeing is open, flexible, accommodative, resilient and unlimited. Conversely, being is closed, inflexible, nonaccommodative, limited or restricted.

5. Some may argue that being and nonbeing are contraries, but that would be strictly on the levei of logic, for logic is still a function within the scheme of beings and falis short of signifying and justifying the realm of being - nonbeing dynamics.

6. Where nonbeing is the foundation of unity, holism, continuity and impermanence, being is the source of dichotomy, permanence, relativism and discontinuity, all of which normally captivate our perception of things but nonbeing nascently resides in all perceptions.

7. Finally, it is not so much a question of being versus nonbeing as it is a serious attempt to realize a truly harmonious blending of both being and nonbeing in becomingness, the well - Spring of the Dharma as well as the Tao or the grounds for intimations with the Truth of Existence. The existential challenge is present, always and openly.

(1)In general, we still maintain the legacy of the British empirical tradition where perception begins and ends with the subject - object relationship. We still do not question seriously the existential (ontological) nature of the subject and object, including both in conjunction, because of our reliance on being rather than becoming. Two anda hall millenia ago, the Buddha objected to this empirical tradition because neither the subject nor the object persists permanently within the impermanent nature of things (anitya). This prompted him to enunciate the famous non - self doctrine (anátman). On close examination, the Buddha’s position is quite sound and supported by contemporary science or Einsteinian physics.

(2)It should be noted that being and becoming do not oppose nor contradict each other. They do not constitute a dichotomy in the sense that being and not - being (not nonbeing ) do. Experientially, it is obvious that becoming rather than being discloses the dynamic nature. In this respect, becoming is the basic metaphysical concept from which everything emerges including any traits or aspects of being.

(3)To my knowledge, Daistetz T. Suzuki was the first to recal the Chinese Zen masters’ use of so - called Zen logic in terms of Westem syllogism: A is A, A is not A, therefore A is A. In our discussion, however, I have used quotes, e.g. “A is not A” and “A is A”, to indicate a deeper nature and meaning based on nonbeing.

(4)Ordinary thinking functions on the basis of Aristotelian three Laws (Principles) of Logic, i.e., Identity, Noncontradiction and Excluded Middle. These are also self - evident “truths” in Eastem ways of thinking. However, with the nature of experience based on nonbeing, the logic of being or entity is expanded to or supplanted by the logic of nonbeing to take on what seems to be a contradictory or illogical nature; to wit, “A is not A.” This logic of nonbeing can also be called the logic of unity.

(5)In Maháyána Buddhism, especially in Mádhyamika thought, agárjuna (c. 150-250 A. D) clearly enunciated the twofoid nature of truth, conventional or relative (samvrti - sat ) and nonconventional or absolute (paramártha - sat ), to exhibit the comprehensive manner in which perceptions function. (Múlamadhyamakakáriká XXIV, 8). In early Buddhism, too, a twofold nature of knowledge was granted: (a) knowledge in accordnace with convention or ordinary perception (anubodha) and (b) penetrative insight into the nature of things (pativedha). (Walpola Rahula, What the Buddha Taught; New York: Grove Press, 1974. p. 44)

agárjuna (c. 150-250 A. D) clearly enunciated the twofoid nature of truth, conventional or relative (samvrti - sat ) and nonconventional or absolute (paramártha - sat ), to exhibit the comprehensive manner in which perceptions function. (Múlamadhyamakakáriká XXIV, 8). In early Buddhism, too, a twofold nature of knowledge was granted: (a) knowledge in accordnace with convention or ordinary perception (anubodha) and (b) penetrative insight into the nature of things (pativedha). (Walpola Rahula, What the Buddha Taught; New York: Grove Press, 1974. p. 44)

(6)Interpenetration does not mean that separate entities, for example, x and y, merely penetrate each otber to forro a unity but that they are mutually involving each other in virtue of the already existing unity of things. This is the foundation of Thorne H. Fang’s unique philosophy of comprehensive harmony. See his The Chinese View of Life (Hongkong: The Union Press, 1956). This is also in accordance with what I have already referred to as the logic of unity or nonbeing.

(7)Once again, it seems quite clear that the dynamics involves a dual aspect within becoming in order to pre-serve the nature of interpenetration, holism and harmony. In this way, both the created and uncreated aspects do no clash but penetrate and perpetuate the becomingness of things. It also means that ordinary perceptions could take on the character of open, wider and deeper perspectives.

(8)Wing - tsit Chan, Source Book in Chinese Philosophy (Princeton:Princeton University Press, 1963) P. 139 The yu and wu dynamics naturally reminds us of the more popular dynamics of yin - yang, but both dynamics, though not equal or identical, still function in similar fashion within the becomingness of things.

(9)Ibid. P. 190

Chuang Tzu, like Lao Tzu, was fascinated with the dynamics of change on both the microscopic and macroscopic leveis, changes that are as fleeting as the galloping horse. In the final analysis, however, all things that change are equalized or evened within the Tao, just as the distinctions “between Chou and the butterfly” blur into indistinction in the becomingness of things. Thus I have interpreted Chuange Tzu’s statement to point at the deeper and holistic nature of be - coming.

(10)In previous papers, “The Aesthetic Nature as a Dialogical Bridge,” presented at the Cambridge University Conference, July 3 - 5, 1992, and “Buddhist Precepts and the Scientific Challenge,” presented at the Chung Hwa Buddhist Institute Conference (Taipei), July 18 - 21, 1992, I have probed into the nature of becoming and brought forth a novel concept of a symmetric - asymmetric relationship and its dynamics. The aesthetic nature arises within this dynamics, the consequence of a proper balance of the correlative symmetric and asymmetric natures. This novel concept will be explored further in subsequent writings.

nyatá which is variously translated as emptiness, nothingness, voidness, etc., and the Taoist notion is wu, variously translated as nothingness, vacuity, nonentity, etc. Wu and

nyatá which is variously translated as emptiness, nothingness, voidness, etc., and the Taoist notion is wu, variously translated as nothingness, vacuity, nonentity, etc. Wu and  nyatá are not identical, to be sure, but they are quite similar in terms of playing the role of effectuating or achieving the holistic nature or grounds of experiential reality. In this respect, they deny any primacy and prominence to the concept of being. But, on the other hand, they penetrate and absorb the realm of being. This inner dynamics of being in the realm of wu or

nyatá are not identical, to be sure, but they are quite similar in terms of playing the role of effectuating or achieving the holistic nature or grounds of experiential reality. In this respect, they deny any primacy and prominence to the concept of being. But, on the other hand, they penetrate and absorb the realm of being. This inner dynamics of being in the realm of wu or  nyatá has always been the starting point as well as the end of all experiences. The Chinese, over the centuries, were able to understand the true import of Buddhist

nyatá has always been the starting point as well as the end of all experiences. The Chinese, over the centuries, were able to understand the true import of Buddhist  nyatá and incorporate it into their own Taoist concept of wu. As a consequence, wu and

nyatá and incorporate it into their own Taoist concept of wu. As a consequence, wu and  nyatá (Chinese k’ung) were interchangeable concepts but the Chinese preferred to express the true holistic experience by wu. For our discussion, however, I shall revert to the currently used term, nonbeing, with the understanding that hereafter it refers specifically to the deep metaphysical dimension of Buddhist andTaoist experience.

nyatá (Chinese k’ung) were interchangeable concepts but the Chinese preferred to express the true holistic experience by wu. For our discussion, however, I shall revert to the currently used term, nonbeing, with the understanding that hereafter it refers specifically to the deep metaphysical dimension of Buddhist andTaoist experience.

agárjuna (c. 150-250 A. D) clearly enunciated the twofoid nature of truth, conventional or relative (samvrti - sat ) and nonconventional or absolute (paramártha - sat ), to exhibit the comprehensive manner in which perceptions function. (Múlamadhyamakakáriká XXIV, 8). In early Buddhism, too, a twofold nature of knowledge was granted: (a) knowledge in accordnace with convention or ordinary perception (anubodha) and (b) penetrative insight into the nature of things (pativedha). (Walpola Rahula, What the Buddha Taught; New York: Grove Press, 1974. p. 44)

agárjuna (c. 150-250 A. D) clearly enunciated the twofoid nature of truth, conventional or relative (samvrti - sat ) and nonconventional or absolute (paramártha - sat ), to exhibit the comprehensive manner in which perceptions function. (Múlamadhyamakakáriká XXIV, 8). In early Buddhism, too, a twofold nature of knowledge was granted: (a) knowledge in accordnace with convention or ordinary perception (anubodha) and (b) penetrative insight into the nature of things (pativedha). (Walpola Rahula, What the Buddha Taught; New York: Grove Press, 1974. p. 44)